A Cage of Roots (7 page)

Authors: Matt Griffin

Fergus caught the branch calmly, holding the burning end with no hint of discomfort. He tossed it back on the fire with a blackened hand.

‘Run!’ Finny screamed and hauled his friends by the wrists.

But Sean resisted. ‘Why?’ he asked the giants, holding his ground. ‘Why do we have to go with you? Why can you only go so far?’

‘Sheridan, for God’s sake!’ Benvy hollered, ‘Let’s get out of here! They’re mad!’

‘Why?’ repeated Sean.

‘Because we will not be strong enough,’ answered Lann.

Taig pleaded: ‘Ayla

needs

you to believe. If we go alone, she will be lost forever.’

The three friends looked to each other. Finny and Benvy couldn’t believe Sean was even entertaining it for a second.

‘We need to talk, alone,’ said Sean.

‘Of course,’ replied Lann, and the brothers moved into the shadows, leaving the friends by the flickering light of the fire. When the uncles seemed out of earshot, Benvy spoke: ‘You can’t believe this rubbish!’

‘We need to go home and call the cops,’ Finny added.

‘What just happened, happened,’ Sean replied. ‘There is no denying that. We saw what we saw. I doubt very much that drugs blow rain in your face and then make it stop in mid-air.’

The other two couldn’t deny that the experience had felt as real as anything. But they couldn’t bring themselves to believe.

‘You only believe them because of those stupid books you read. Life isn’t one of your dumb fantasy books!’ Benvy said, a little hurtfully.

‘Benv’, easy,’ Finny interjected.

‘Yeah, well … I believe there is more to life than we think, Benvy,’ Sean retorted, ‘And I think Ayla’s uncles just proved that.’

Long into the cold night they argued, conferred, pleaded and debated. Then the uncles led them through the woods towards home.

A

yla measured the time by counting endlessly. She had decided that trying to think of anything else was a waste of time. Dwelling on home only tortured her, and thinking on her predicament was even worse. The discomfort, the heat, the lack of air was all torturous, but worse now was the smell. She had to scratch holes in corners to go to the toilet and as she couldn’t make them deep with only her bare hands, they had filled the cell with a pungent stink matched only by the goblins’ food.

So she counted, putting

Mississippi

between every number for accuracy. She did it out loud, in a sort of chant that seemed to calm her. She also made up tunes and sang the numbers in rambling melodies. Worst was when she lost count. It shouldn’t have mattered, but

when it happened she screamed in frustration and sobbed, beginning all over again from zero.

The goblins had come every couple of hours, to throw in another bowl of wretched slop or a jug of gritty, stagnant water and to taunt her with ever more vicious barbs. When they ran out of inventive slurs, they jostled and pushed her, hissing in her face and scampering in and out of the opening to the tiny cell like excited rats. They seemed so full of hate for her, so eager to hurt and scare, restraining themselves only at the last second like rabid dogs on a leash and seething with resentment that they couldn’t finish the job. Evidently, they had orders not to hurt her too badly. One goblin had screeched:

‘Oh to hurt you, little piglet. Oh to strike your face, bang your head, leave you for dead! But we can’t. Such a shame! The king’s orders! Only for now though, piglet. Your time will come soon!’

Knowing that they couldn’t really touch her didn’t make these episodes any less frightening. They were so energetic in their contempt for her, bounding in and out of the cell like ricocheting bullets and hollering abuse. After each visit, it took an age to stop shaking. Then, when she was still again, she would commence the long and endless count to sixty.

After hours of this, the time-keeping became automatic. Despite her determination to concentrate on the numbers, her mind would wander involuntarily, and more often than

not stumble into visions of the creatures. The two globes of their eyes hung aglow in the air wherever she looked, like sunspots, until there was no escaping them. They haunted her as she huddled in the corner of her cell with her head bowed between her legs, as if by curling up into a ball and not looking up she might somehow escape the nightmares.

The gruel was still utterly vile. There was no getting used to it, but occasionally and with a vast effort, Ayla had to eat it or starve. The food stung as it went down.

It smells like old diesel,

she thought, remembering the acrid whiff from her uncles’ machinery.

Only stronger. This must be the most flammable stuff on Earth

.

After she’d managed to get it down, she braced herself against the convulsions, concentrating on keeping the slop in her stomach so as not to waste the effort by returning it all to the floor. It wasn’t easy. Every bodily impulse rejected the porridge with gusto, hurling it back up her throat in protest. But Ayla’s iron will kept the food down. When the latest bout of gagging eventually subsided, she lay back, totally spent, and resumed the counting of her inner clock. She thought about the smell of diesel again. And then she had an idea.

Finny, Benvy and Sean all agreed this was an impossible

situation. They couldn’t deny what they had seen in the forest clearing, even though they wanted to. As they trudged back through the woods, led by the uncles, they had time to group and talk more about what was happening. It was completely insane: that was the first fact. And the second fact, which Benvy and Finny still only reluctantly agreed to, was that what they had witnessed was some kind of magic. The third, which they reluctantly accepted, was that if they wanted to save their friend, they would have to do what Lann asked of them.

Daylight had broken before they left the stone circle, and by now they were in deep, deep trouble with their respective families. To compound the problem, they were given very little time at all to devise their invented excuses (staying at each other’s houses). They had to get home, grab some spare clothes, food and water, and meet back at Ayla’s house as soon as possible.

Finny left with the uncles in their jeep. They would drop him home and wait for him outside, as he would meet the least resistance from his family. It was only his mother, and she generally tried to avoid any major conflict with her son, indulging, through guilt, his haphazard behaviour. She would probably be in bed anyway, he reasoned, and so he planned on just walking in, quietly taking what he needed and leaving without a fuss. It was Lann who convinced him to leave a note to say he had left for a match in Dublin

and wouldn’t be home for a day or two. The truth was, Lann said gravely, he mightn’t be home at all.

Benvy and Sean had hovered at the wall by the forest edge for a while, plotting their own escape. They were in a panic because, in both cases, their parents may well have called the guards, and they certainly would have checked with each other as to the pair’s whereabouts. It was almost eight-thirty am by Benvy’s phone: their folks would have been up for hours, with ample time to work up a frenzy. There was no time left to deliberate now. They looked at each other, sucked in a deep breath and agreed to meet back at the forest car park in half an hour.

Sean slipped his key into the door and glanced skywards, offering a prayer, pleading with the gods that this might go without a hitch. Before he could turn it, the door swung open and his mother filled the doorframe, furious, while his father hovered behind her.

‘Sean Sheridan, where in God’s name have you been?’ she shrieked, grabbing his lapels and hauling him into the hallway. She gripped him to her chest, kissing his brown curls feverishly, and stepping back to deliver a crack over the back of his head.

‘Now, Sean, you had us worried sick. Your mother is beside herself,’ his father added, while his mother delivered more angry kisses.

‘Explain yourself this second!’ she demanded, pulling him

into the kitchen. ‘We were just about to call the guards. The Caddocks are worried sick too! Where is Benvy in all of this? What have you two been doing? Ah, God, Sean, you’re frozen!’ She was pinching his cheeks now and inspecting him all over.

‘And the muck all over your shoes! And you’re soaking! I could kill you!’ she added.

‘Your mother could kill you, Sean, so she could. Where were you, for God’s sake?’

‘Mum, I’m fine!’ said Sean nervously. ‘I told you we were staying at Finny’s.’

‘You never in a million years told us you were staying at the Finnegans’, Sean.’ His mother didn’t believe him for one minute.

‘You never told us, Sean,’ echoed his father.

‘I did! It was planned ages ago! I told you about it, eh, last week! I told you last week that Finny was having a … a party. For his birthday.’ Sean gulped, ‘And we were staying there for the night.’ This was going to be a tough sell.

‘Sean Sheridan, Oscar Finnegan’s birthday is next month, so pull the other one. I know because Samantha is throwing a big bash at Quasar, and we’re all invited. So, try again!’ His mother’s face was puce now, the relief fully replaced by pure anger.

His father put the kettle on. ‘You’ll need some tea to warm up,’ he said.

‘He can bloody well explain himself first!’ his mother hollered.

‘No, no, I’m grand thanks, Dad. I have no time, I have to head out again!’ Sweat was forming in globules on Sean’s forehead.

This was too much for his mother.

‘Sean Sheridan, I tell you now, you are going nowhere until you tell me what you have been doing, where you have been doing it, and why your clothes are filthy and your shoes are covered in muck!’ The threat in her eyes told of a terrible fate if her questions were not answered.

Sean needed to play this one like an Oscar-winner. ‘Mum, I’m really sorry for worrying you. I honestly told you last week that we were staying at Finny’s for our own birthday party – just me, him and Benvy. And Ayla, of course!’ he added, over-enthusiastically. He made a mental note to kick himself over this later.

He struggled with an impulse to come clean and tell them everything – he never lied to his parents. But he continued, ‘So we went there after school, and walked back through Coleman’s this morning.’

‘That explains the shoes, Mary,’ his father said, and was shushed instantly.

Sean’s mother looked intently at her son, boring into him, willing him to crack and tell the truth. The globules

turned to rivulets, running down the creases on the boy’s forehead.

‘I also would have told you, I’m pretty sure, that today is the tour of King John’s Castle. We’re all going for history class. So I’m only home to change and get a lunch and then head to school for the bus. Then there’s a film to watch about it or something, back at the school, like. And then we’re going to Cashel.’

‘Cashel in Tipperary, on a Saturday?’ his mother asked, lip curled in doubt. ‘Sean, I don’t recall any of this.’

‘We are, Mum!’ he pleaded. ‘We’re going on a special history day, to Limerick and then on to Cashel to see The Rock of Cashel. And we’re staying overnight.’

He could barely stop himself from wincing at his own lies. His mother’s glare dug ever deeper, her frown burrowing down to the tip of her nose. The doubt was plastered all over her.

‘I’m going to call Mrs Marnagh,’ she announced, reaching for the phone.

Sean nearly lunged out in alarm, but was stopped in his tracks by the doorbell.

‘That’ll be Una Caddock. Jim, get the door, would you?’ The phone beeped as Sean’s mum scrolled through the contacts list, searching for the principal’s number. She found it and pressed the call button.

Before the phone was at her ear, Jim Sheridan’s voice

called from the door.

‘Mary, you’d better come to the door. Sean too. The Guards are here.’

Sean’s heart iced over and fell crashing into the pit of his stomach.

The creatures were due to arrive with more slop and vicious words any minute. Ayla’s pinecone throat made it impossible to swallow. A hundred times she told herself:

This is a bad idea

. A hundred times she convinced herself not to go through with it. But each time, battling her own will, she determined that it was her only hope of escape.

She would have to be lightning-quick to pull it off, especially as her captors were so agile themselves. And even if she was fast enough, there was no guarantee it would work. Then she would surely be punished very severely for having attempted it in the first place. But it was worth it; it had to be. She waited in the dark.

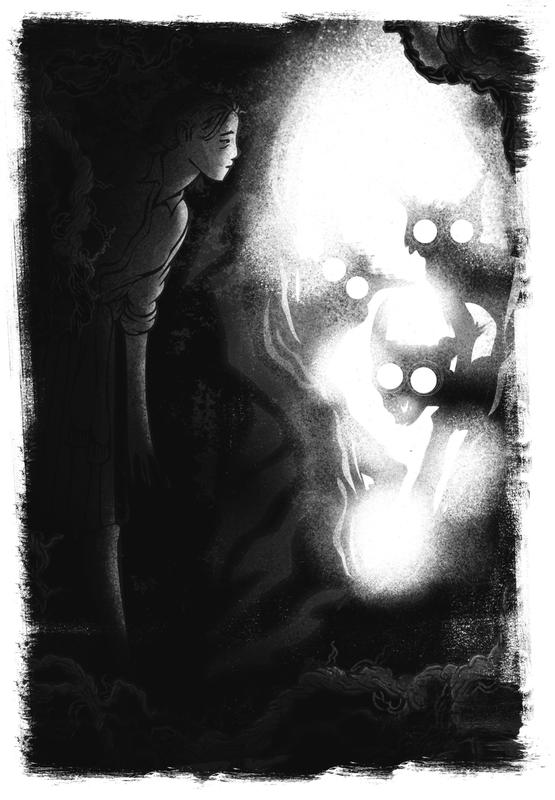

When the first chink of light appeared in the wall, Ayla darted across the cell to crouch beside the opening, pressing herself back as much as she could to avoid being seen. The hole grew and cast more light in to the cell. Ayla held her breath as the first goblin entered, followed by a second – the torch-bearer. There was no time to think. As the first

turned and saw her, she leapt, pushing herself off the wall as hard as she could, aiming directly for the goblin with the torch. In a second the first one was on her back, trying to push its long fingers into her eyes and nose, and gripping her neck with its other hand. But her arms were still free, and she lashed out at the creature beneath her, saw the flaming stick in its hand and grasped it.