A Cage of Roots (17 page)

Authors: Matt Griffin

‘Gross!’ said Benvy.

‘There’s another door.’ Sean was pointing to another opening directly across from the one they had come through.

They climbed up to it, but found little more than a burrow. The noise was clearly close now, and so they helped each other in and crawled, pushing their burdensome weapons in front of them. Ahead was light, and the chilling sound of baying crowds: shriek upon shriek, howl upon howl. They forced their way along to its source.

They emerged on a ledge, where there was just enough room to lie side by side on their stomachs. Slack-jawed, neither could speak. From their perch they gazed upon the immense hall with its mammoth pillars. The broiling black of thousands of goblins, swarming over each other, eyes like full moons and red mouths squealing, was like looking into hell. To the right, the great hall stretched away, impossibly high and wide, ending in the most dizzying sight of all. On a towering stone throne was the form of a bearded man, thirty metres tall, made entirely of roots. At his feet stood a wooden machine, like an old catapult, but it was almost impossible to make out more.

Then Benvy realised she could make out a familiar figure. She shouted, ‘

Finny

!’ And with that, she leaned too far over the rocky lip. She fell.

Sean only hesitated for a second. He took the hammer up into both fists, stood on the edge of the tiny platform and leaped, roaring, into the throng. It was a huge jump, out and over the mass of black creatures, between the pillars and down, down, down. As he dropped, he raised his weapon over his head, and as the ground rushed up towards him he brought it down to fall upon the stone floor.

It cracked the earth like an eggshell, hurling the shrapnel

of thick stone into the air around him. A wave of muck and rock rushed off in a circle around him, carried on a disc of blazing blue light. It smashed through the swarm, pitching the creatures into the air in their hundreds. Cracks rushed up the four nearest pillars like snakes, and the roof rained dust in blinding swathes. The whole hall shook violently, as if it was being throttled.

Sean coughed out a cloud of dry muck, and took his hands from the shaft of the hammer. His glasses were coated in grime; he wiped them on his shirt, but the lens that had been cracked was now smashed. He looked around him, then down at his legs. He was in one piece at least. The hammer was buried fast, halfway into a massive slab of granite; there was no removing it. Around him was a thick fog of dirt, and pieces of the hall still slipped and crashed to the ground. There was no other movement.

‘

Benvy

!’ he yelled, and again, ‘

Benvyyy

!’

He ran over to where he guessed she had fallen, and there she was, out cold. There were no goblins around her. A fresh trickle of blood ran from her forehead; in her right hand, she still clenched the javelin. Sean rushed to her side and took her head in his lap, gently slapping her face and begging her to wake up.

‘Benvy, please! Please wake up!’ he pleaded. He wiped the blood from her head, and saw that it was only a scratch. Her eyes opened, and blinked, darting around in confusion.

‘Thank God!’ he shouted. ‘I thought I’d killed you!’

‘What … What the hell?’ Benvy was still confused. Then she jolted up. ‘Finny! Sean, I saw Finny. He’s here! They have him!’

From behind the smog of debris, there was a deafening roar and a blast of searing heat. The two hurried to their feet and looked into each other’s eyes. Without saying anything, they nodded and ran in the direction of the roar, as the cloud began to dissipate.

Around them, hordes of goblins were getting to their feet, lamp-like eyes sending beams into the dust like spotlights. Ahead, the monstrous form of the king was pulling great chunks of stone from its legs: he was half lying between the two split sides of his broken throne. In front of him, the wooden platform had been damaged, but remained working, and they could see the strange cloth of light flowing out from it and over into the shadowy eaves.

Directly in front of them, the body of Finny was limp, in the grip of a dozen creatures. They were pulling at him and thrashing him, even though he was unconscious. As they ran, Sean and Benvy could see their friend was bloodied and badly beaten.

All around them, the black things were rising to their feet and beginning the chase. The monstrous king had freed himself, and now rose with a bellow of fire. Benvy raised the javelin over her head, and threw it with every

ounce of strength she possessed.

It tore through the air in a blaze of white and a head-bursting scream. The whole hall was bathed in its blinding glow as it shot like a hot bullet straight into the chest of the king. To either side, creatures fell to the ground, with bleeding ears, yelping and clawing at their own eyes, howling in pain. The group that held Finny rolled away in blind agony, leaving him slumped on the ground. His two friends rushed to his side and lifted him up. He was badly cut; his face, torso, arms and legs were shredded, his clothes sodden with blood.

‘Wake

up

!’ they shouted at their friend, frantically checking to see if any of his cuts were fatal.

‘Please, Finny!’ they begged, ‘Please, just wake up!’

From what they could see, the wounds were deep, but he wouldn’t bleed to death.

He groaned and spat out a glob of blood.

‘Ayla …’ was the first thing he said.

‘Yes! Finny! Up you get now! You’re hurt, but we can get you out of here!’ Benvy shouted.

‘Ayla …’ he repeated.

‘We don’t know where she is!’ Benvy said, ‘We need to get out of here and figure out what to do. We need to get you out and see if we can patch …’

Sean put a hand on her arm.

‘There’s no getting out of here without her,’ he said. ‘We

may as well die trying.’

Benvy couldn’t reply. Her mouth had dried, and the words were stuck. But she knew Sean was right.

Over the surrounding rubble, goblins were pouring, scratching at each other to get to them first. Then another deafening, thunderous roar came from behind the platform. The king had risen to his feet. They could see a burning hole in his chest where the javelin had entered, but the singed wound seemed to have had little effect. His eyes widened, red infernos in the veil of dust.

‘KILL!’

The voice gripped their ears in fists of sound. They covered them and squeezed their eyes shut against the pain. The goblins were nearly upon them.

W

hen the creatures were close enough to pounce, Sean threw himself in front of Benvy, ordering her to stay behind. She wrenched him back with one hand, and held him there with the other.

‘Finny!’ she yelled above their baying, ‘Your sword! You have to get to Ayla!’

Finny looked around frantically for the weapon, but it wasn’t on the ground.

‘Go!’ his two friends shouted in unison, readying themselves for a fight to the death, their backs to each other.

Finny put a first foot on the wooden structure. Behind him he heard the slavering growls of the goblins as they leaped onto his friends; he heard Benvy and Sean shouting in the fray, each ordering the other to save themselves. But he didn’t turn to look. He climbed, wincing in pain and bleeding heavily.

At the top, the machine was busy, shunting left and right, pulling a thread of bright light from something unseen behind part of the structure, and weaving it into a thick tapestry. It was damaged from the shockwave of Sean’s hammer. It slouched now where one of its huge wheels had snapped off the axle. On the same side, the granite had split and part of it had fallen to the ground. Motionless black arms and legs could be seen under the fallen slab. Three of the goblins had rushed to replace their fallen comrades, and worked feverishly at the loom, pulling the thick weave and passing it on to others on the ground below.

They had not yet seen Finny. He pulled himself painfully up over the top of the whole structure, moved behind the upright frame and ducked underneath the jostling beams. Then he had his first piece of luck: the sword was leaning against a balustrade, right by the feet of the goblin workers. He summoned his strength and went for it.

In four long leaps, Finny made it to the weapon, grabbed it and sidestepped the first assailant. Once again, just as in the dim basin where he faced the changeling, he imagined himself in a match.

They’re just other players,

he convinced himself through the fear. He ducked the next as it swung a haggard claw at his head, and in one movement struck the third on the head with the flat of the blade.

His own wounds opened wider, and his body howled

at him to stop, but he ignored it, spinning around to jump a low swipe, and pushed forward with a shoulder into another goblin, knocking it over the side. His last deft turn put him beside the third goblin as it went for him again. He knocked its claw away with his hand and swung at it with the sword. This time he used the edge: the blade went through the creature’s arm like it was butter, and the thing wailed and jumped over the side, the severed arm twitching angrily by Finny’s feet. The whole structure wobbled as more goblins scaled it. He turned, searching for an escape, and saw his friend.

Ayla was held up at an angle, arms and legs strapped in leather and bound in chains. From her neck, the glimmering thread protruded up into the loom, unravelling her. Only her face and one arm remained; the rest was night-black and contorted. She was turning into one of them.

‘Ayla!’ he shouted, but his cry was lost in the thunderclap of the king’s red-hot bellow.

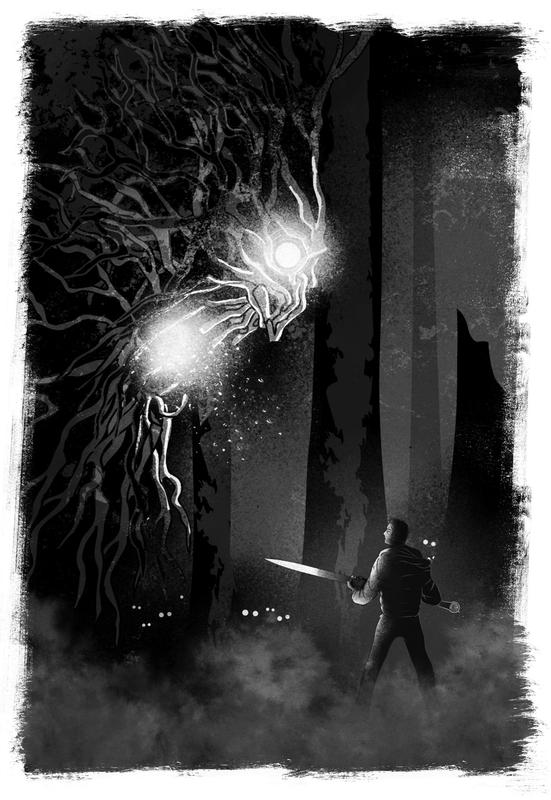

The vast king towered over them, spitting ash and firefly sparks. The vines of his arm squirmed and slid together as he reached down and knocked Finny into the air. He landed hard against a pillar and slumped to the ground. The boy’s wounds were leaking, hot and wet on his cheek and arms. His vision blurred and everything around him tilted. He felt sick as he tried to get to his feet, and toppled over on to his head, rolling on the floor. Still he tried to lift

himself, but his legs had turned to boneless lumps.

Finny could hear the crashing stomps as the gargantuan king approached again; he could just make out the jostling herds of goblins, holding each other back and cackling, slapping their hands on the floor like frenzied apes, bloodthirsty and ravenous for his death at the hands of their master.

He focused on the fabric of light that stretched over his head, and followed its course between the pillars. The stomps grew closer as he saw the wretched shape of the half-finished root-woman dangling from the wall, where the weave knitted itself into her: arms, chest, stomach and the frightful head, whose face tugged at the wall to be free, and screamed with the sound of a hundred banshees.

Finny staggered like a drunk as the first blow came down on the ground beside him, casting him into the air like a rag doll. Again he pulled himself up, forcing the sick back down into his stomach, sticking his chin out and holding the sword up weakly. Finny tried to shout something, but he had no strength. The red root king brought its fist down again in a huge detonation, right beside the boy, knocking him back to the rubble – he was so close to death, he could feel its cold clutch.

‘DIE!’

The shock of the king’s growl split Finny’s ears and wrenched at his brain, and for a second he was lost. He

let the dark curtains of unconsciousness close around him, taking sad comfort in the slow slide to oblivion. And suddenly he was in the woods – in Coleman’s, in their little place. And he was angry, swinging his hurley at the leaves, spitting out every bad word he knew and cursing his life. And Ayla was there, saying nothing, letting him do it. And when he tired and slumped to the ground, she put her arm around him. She lifted his face by the chin, looked at him with those vivid-green eyes boring in … and she said, ‘You’ll always have me.’

And he woke.

He placed the point of the blade on the ground, and hoisted himself up to standing. The demon king stood before him, about fifty metres away, vast and cruel and grinning. The hordes encircled him, whooping and crying out for him to die. The vile figure on the wall strained at her own body, pulling the thread into herself, the fire in her eyes and mouth coming alive – indicating that the process was nearly complete. It was the evil queen, Maeve, Finny knew now. And only Ayla’s death would set her free.

He held the sword by his waist, one hand on the handle and the other on the end of the blade, just as he would his hurley before a free. He parted his legs to steady his stance, sidelong to his target. And he whispered to the weapon, ‘Let’s see what you can do then!’

He brought the sword up behind his head, took a few

steps forward and swung. The weapon sang, slicing the air and shining effervescent blue. As it travelled, the blue grew longer, an extension of the blade – ten metres, twenty, thirty. It bit into the roots of the king’s crown, severing them cleanly – as if there was nothing there at all. Finny spun on his feet, the light retracting as he brought the sword down, in the same movement, onto the weave. The threads disintegrated.

Finny looked to the king. The monstrous mangle of roots gazed back, its face contorted into a look of shock. The behemoth could only watch as the weave-light dimmed and went out. It saw its lover writhe, unfinished, on the wall. It regarded Finny, and tried to reach out a hand, but the flames in its eyes and mouth dimmed and then died out. The king crashed to the floor in an explosion of wood and dust, the brittle roots snapping as they fell.

The only sound now was the desperate wailing of the queen, and though that pierced like a pin in his ears, Finny realised she could not move from the wall. The goblins were silent and motionless. They didn’t rush the boy or attack, or even howl at him; they just stood and stared with those round, pale eyes.

Finny half-limped, half-ran to the loom and, with great effort, climbed the steps to Ayla, or what was left of her. He had stopped the thread just as it reached her chin. Nearly all of her was transformed, and she didn’t move. He

cut the bonds and lifted her onto his shoulder. Where the skin was black she was ice-cold, but her cheek felt warm against his. He made his way down slowly, fighting the urge to collapse. Behind the loom, where he had last seen his friends, he found Benvy, hunched over an unconscious Sean, weeping. Both of them were covered in cuts.

‘Finny! You did it!’ Benvy said, trying, but failing, to smile. ‘I missed the whole thing; just woke up. Is Ayla okay?’

And then she saw the slumped figure in his arms, half-transformed, with those jagged goblin limbs.

‘Oh Finny! She’s …’

‘She’s turning into one of them. We have to go, Benv’. These things are going to let us, I think. But I don’t know how long that will last. Is Sean okay?’

‘He wouldn’t fight for himself,’ she lamented. ‘The big eejit kept fighting them off me. He’s hurt badly, Finny. He won’t wake up.’

Sean’s face was coated in dark blood, his eyes bound shut where it had dried over them.

‘Let’s go.’

Sean coughed and groaned, a trickle of blood snaking down his chin.

‘Oh, thank God!’ shouted Benvy. ‘Shush, don’t talk. Can you walk at all?’

Sean could only answer with a pained moan, but did his best to get to his feet with her help. He was still heavy,

and she almost collapsed, but righted herself and nodded to Finny to follow. It was only as they walked that they noticed all of the goblins slinking away into the shadows under the broken pillars.

Benvy had a good idea of how to get out. Taking a torch from the wall with her free hand, she led them through the labyrinth. The caterwauling of the half-queen haunted them as they struggled through the undulating passages, but it lessened with distance, and by the time they turned left at the last junction, it was only the echoes that reached them. They climbed on, their hearts fluttering as they recognised the tunnel they had first come to, and knew that they were at the gate. Before they could wonder at how to open it, the earth parted before them and they blocked their eyes against the warm, wet daylight.

The three friends did not have time to talk, or to allow their stinging eyes to adjust. They felt themselves dragged out of the hole by huge hands, and set down on the wet stone to suck in lungfuls of air. They could hear Lann and Fergus speaking, but they allowed themselves another minute to breathe and for their day-blind eyes to grow used to the outside. When at last they could look, they were shocked at the sight of all three giant brothers.

Gone were the broad shoulders and tree-trunk arms. Gone was the hair of black, red and blond. All their features were lost to age, drained and shrivelled and cracked. Heavy bags swung under yellowed eyes. Their cheeks had sunk and sagged. Their backs were hunched, the spines prodding through white, translucent skin. Taig looked the worst; he was toothless and frail, barely able to lift his head. He sat alone.

‘You’re …’ Finny started.

‘We’re dying, lad,’ the old shell of Lann said. ‘The price of returning home.’

Fergus did not speak. He was arranging Ayla’s limp body among a circle of small stones. To see the once-mighty Fergus struggle with the weight, where once he could have lifted her with one finger, was a sad sight. He was muttering curses under his wispy white beard, and coughed in a dry hack from his failing lungs.

‘Can you save her?’ Finny asked. His own wounds were grievous, and he couldn’t get up. ‘Can you save Ayla?’

‘We can,’ Lann answered.

Bleak clouds had gathered, and the atmosphere was heavy. Finny noticed the hawthorn tree had wilted to a charcoal stump like a grasping hand. His wounds throbbed. Sean had slipped into unconsciousness again, and Benvy was trying to wake him, with no luck.

Fergus stood over them. He kneeled slowly down beside

Sean and placed a tender hand on the boy’s forehead. While Fergus’s body was frail, draped over like a brittle skeleton, his hands had not changed – they were still heavy and thickset.

‘It looks like you could do with some healing yourselves,’ Fergus said, his own gash now a scar lost among the wrinkles. ‘We can help. Have faith.’

Benvy thanked him, but nodded to Taig.

‘Why is

he

still here?’ she asked scornfully.

‘He is here to amend,’ Fergus replied. ‘He’s our brother, Benvy. You should forgive him.’

She looked at him again.

‘I don’t think I can.’