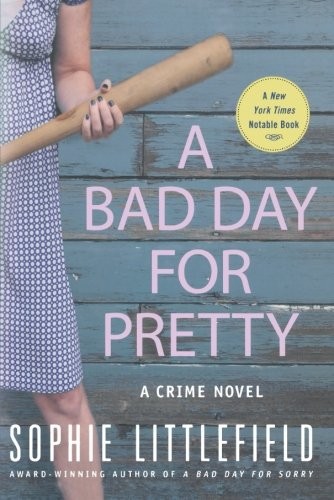

A Bad Day for Pretty

Also by Sophie Littlefield

A Bad Day for Sorry

A BAD DAY FOR PRETTY

SOPHIE LITTLEFIELD

Minotaur Books k

A Thomas Dunne Book

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

A THOMAS DUNNE BOOK FOR MINOTAUR BOOKS.

An imprint of St. Martin’s Publishing Group

A BAD DAY FOR PRETTY. Copyright © 2010 by Sophie Littlefield. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.thomasdunnebooks.com

www.minotaurbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Littlefield, Sophie.

A bad day for pretty / Sophie Littlefield.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-312-55975-5

1. Middle-aged women—Fiction. 2. Abused women—Fiction. 3. Murder—Investigation—Fiction. 4. Women—Crimes against—Fiction. 5. Missouri—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3612.I882B32 2010

813′.6—dc22 2010008709

First Edition: June 2010

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For T-wa

Never was there a prettier baby

Acknowledgments

I am so very grateful to Toni Plummer, my talented and sharp-eyed editor, and Anne Gardner, who showed me exactly how an ace publicist does her job.

And then there’s Barbara: without the guidance of my agent Barbara Poelle, my books would be wan and lesser things. Thank you for steeling my resolve, encouraging my excesses, and finding perfect homes for the stories.

To my friends: Huzzah! My old girls plus the new Pens … my poker pals, even those who had the temerity to move away … my tour (and scotch) partner … my RWA and MWA and SinC friends … and Roseann and Cheryl and Jan and the G-F’s and P’s for sticking with me.

How can I adequately thank you: Bob, kids, Mike and Lisa and Kristen and Maureen—your encouragement and love fuels me.

Prologue

JUNE 1966

Mama was already down in the cellar with Gracellen and

Patches. Gracellen was four years younger than Stella—just

a baby, only three—so all she cared about was Mama said

they could light candles and make a tent with blankets on the card table. Patches knew something was wrong, though—she whined and

paced in circles, her toenails clacking on the floor and her tail between her legs

.

Daddy said Stella could stay upstairs for a few more minutes while

he and Uncle Horace got ready to go help the trailer park people. It

wasn’t part of their regular job—Daddy and Uncle Horace were Missouri Highway Patrolmen—but when a tornado came, everybody had to

help

each other out, ’specially if it was a bad one. And this was going to be

the worst one since sixty-one, Daddy said

.

The special radio crackled and buzzed in the front room. “Winds up to two hunnert ten,” a man’s voice drawled

.

Outside, the sky was turning green. The little trees the Marshes

had planted in their yard next door looked like they wanted to bend over all the way down to the ground. Jamie Marsh’s tricycle went driving itself down the driveway sideways, then flipped over onto the lawn, where it sat upside down with the wheels spinning

.

Daddy and Uncle Horace were loading the big metal box of first aid stuff into the trunk of Horace’s old blue car, along with flashlights and coils of rope. They might have to drive folks from the trailer park

over to the high school—that’s where the Kiwanis were setting up coffee and sandwiches and cots. Most people would already have drove theirselves, Daddy said, but you never knew when people were going to get stubborn

.

Stella stayed on the porch as hail clattered on the roof. A flash of

lightning made her jump, and she counted—one one-thousand, two one-thousand, three one-thousand, four—before the thunder exploded like

it was right down the street. Stella could feel the crash in the floorboards

,

up through her feet into the middle of her tummy

.

“Now you go on down with Mama and Gracie,” Daddy said

,

climbing back up on the porch for a last kiss on the cheek. Rain dripped from his slicker and his cap, but he didn’t seem to care, so Stella decided

she wouldn’t either, and she didn’t wipe away the wet kiss from her cheek. “Be good.”

“Bye-bye now, Stella-Bella,” Uncle Horace called from the drive, giving her a little salute

.

“Come back soon, Daddy,” Stella said, her voice small under the sound of the whipping winds. “I’m scared.”

“I’ll be back before you know it, sweetheart,” Daddy said. Behind

him, Horace sang the silly song he always sang for her: Stella Stella

,

Bo-Bella. “But we have to go help these folks first.”

“Why do you got to help them?”

Daddy laughed, his smoky voice booming and big. “Why? ’Cause helpin’ folks is what men do when they grow up.”

Stella shut the front door tight like Daddy said, and ran down the stairs to the cellar, where it was warm and cozy and Mama had a plate of pecan sandies and a cup of Kool-Aid ready for her

.

By the next morning, Uncle Horace was dead. A shard of metal window casing broke off one of the trailers in the whipping wind, flew through the air, and pierced his heart

.

ONE

This’ll put hair on your chest,” Sheriff Goat Jones said, handing Stella a little spice jar. His legs were so long that his knees brushed against hers under the old pine table, causing a feathery quiver to flutter through her body.

“Hot … pepper flakes,” Stella Hardesty read, squinting at the label as she accepted the uncapped jar. Her reading glasses were home on the bedside table. She wasn’t planning on needing them tonight. She’d had her eye on the sheriff for just about as long as he’d lived in Prosper, and she figured she had his fine form just about memorized.

“Yeah. Really, go ahead.” Goat gestured at the steaming plate of chicken and dumplings, silky sauce pooling next to bright green beans tossed with slivered almonds. “Whenever dinner seems like it needs a little something extra, that does the trick. Gets the eyes to smartin’, you know?”

Stella nodded, but she didn’t know, not really. Her dead husband, Ollie, had never cooked so much as a can of franks and beans, though he’d spent the twenty-six years of their marriage complaining about

her

cooking. A man in an apron was still a novelty to Stella, but she thought she might be able to get used to it.

Three years, six months, and three days after Ollie died, here she was having dinner with a man who cooked, cleaned, didn’t pick his teeth, and had never hit a woman in his life. Things could hardly get any better, so why was she so nervous?

Stella hadn’t reached the half-century mark without seeing a little of the world. She had been to Kansas City. She’d eaten in a damn four-star restaurant. She knew which fork to pick up when, and she could fake her way through a wine list, and it had been several decades since she’d felt obliged to leave her plate clean.

But closing her fingers around the little bottle, brushing the sheriff’s broad-knuckled, strong fingers with her own, she more or less forgot how to make words into sentences and found herself shaking the jar in rhythm with her own pounding heart, all the while unable to look away from those blue-blue eyes, which even in candlelight spelled

t-r-o-u-b-l-e

in spades.

“Damn, Stella. … I guess you like it hot,” Goat said, watching the pile of pepper flakes accumulate on top of her chicken.

Stella felt the blood rush to her face and set the jar down on the table with a thud. Goat had been having that effect on her since the first time she laid eyes on him, but the difference nowadays was that instead of giving her a rosy glow, blushing turned the network of scars on her face bright pink.

It had been three months since her last case sent her to the hospital with a couple of bullet wounds and sixty-eight stitches—most of them in her face—but the other guys had fared far worse. Three fewer scumbags polluted Sawyer County, Missouri—four, if you counted the wife-beating husband of Stella’s client Chrissy Shaw, who’d practically died of sheer stupidity. Well, that and a Kansas City mobster in a bad mood.

Stella had healed up mostly fine, and even managed to drop fifteen pounds from eating hospital food, and just last week Sheriff Goat Jones had invited her to dinner to celebrate her return to health.

All of which was great. Except for one little tiny problem: though Goat had done some creative fact-spinning on her behalf to ensure that all the potentially incriminating loose ends were tied up after her bloody bout of justice-wreaking, the fact remained that he was a shield-wearing, rights-reading, example-setting enforcer of the law, which put him just about exact opposite Stella where it mattered.

Stella dealt in matters of crime and punishment, too. Only her methods weren’t exactly endorsed by the Police Union. Her brand of justice was doled out in secret, in back alleys and secluded shacks, in the dead of night, far away from any citizens who might be startled by the screams of the latest woman-abusing cretin who was having his attitude adjusted.

Because that woman was Stella Hardesty, who’d taken her own husband out with a wrench those three and a half years ago—and who never intended to let another woman get smacked around if she could help it.

And usually, Stella

could

help it. Could help the woman who heard about her in a whispered conversation, who tucked her name away in a far corner of her mind, until the day came when things finally got so bad that there were no other options. When the courts failed, when the restraining order didn’t manage to restrain anything, when the man who promised he’d never do it again at ten o’clock forgot his promise by midnight. When a beaten woman finally picked herself up the floor and washed off the blood and took inventory of the latest bruises and something snapped and she decided

this

time was the

last

time—when that day came, she knew where to go, and who to see: Stella was ready for the job.

“So…” Goat lowered his fork to his plate and regarded her expectantly.

Stella smiled wildly, casting about for something clever to say. It was ridiculous; never, during the many times their paths had crossed in a professional capacity, had she had any trouble talking to the man. Even when she was trying to keep him from figuring out exactly what the hell she was up to. Which, now that she thought about it, described nearly all their conversations.

“Seems like it’s raining even harder,” she settled on, immediately regretting it. Jeez—she couldn’t come up with anything better than that? They’d already discussed the tornado that had come blowing through town earlier in the day. That had seen them through the appetizer—how she’d heard on the radio on the way over that it was a four on the EF scale, enough to pull up trees and toss around cars. In fact, the announcer reported that the twister had taken out some utility sheds and a snack shack out at the fairgrounds.

They didn’t use the EF scale back when she was little. Stella didn’t know what the tornado that killed her uncle Horace had been rated. But the memories from that night stayed fresh—the waiting, the sounds of the winds beating at the house above them … the terrible heaviness of her father’s tread on the stairs when he finally returned.

“You okay there, Dusty?” Goat said, peering at her closely.

Stella took a breath. The memories still made her catch her breath, made her heart beat a little faster.

“I’m fine. Just … I wonder if there’s gonna be another one coming through.”

“Well, there might,” Goat said. “They didn’t downgrade from the Tornado Warning to a Watch yet—least, not before I turned the scanner off. They got a wall cloud over in Ogden County, looked to be going almost thirty miles an hour northeast. Guy on the radio said they had a report of a waterspout over the lake, down by Calhixie Cove—that was right before you got here.”

Stella’s eyes flicked over to the scanner on the kitchen counter. It was a sleek, compact thing, a far cry from the clunky NOAA weather radio her daddy owned when she was a little girl. Buster Collier turned it on the minute the sky darkened, and listened to the storm reports like other men followed the Cardinals. How many times had her mother scolded her father to turn off the radio when she put dinner on the table? That was her dad, though—especially after Uncle Horace was killed. It was like he couldn’t bear not knowing, like if he turned away from the radio, the storm might rage out of control and snatch away something else dear to him.