A 1950s Childhood (4 page)

Authors: Paul Feeney

Window cleaners were plentiful, with their stepladder and bucket anchored onto their pushbike. Sometimes window cleaners would carry their stuff in a homemade wooden box (like a sidecar) attached to the side of their bike. Most people didn’t have the money to pay for window cleaning and so they did it themselves. It wasn’t beyond a window cleaner’s cheek to knock and ask for a bucket of clean water, even if he hadn’t cleaned your windows!

The gas and electric meter men would come regularly to empty the meter-boxes of cash. Most people paid for their gas and electric as they went, via ‘shilling in the meter’ boxes, which the meter men padlocked and sealed with wire and wax. The meters were set to overcharge and so you would usually get cash refunded when the meter was read. Fish and chips tonight!

Paperboys were a common sight in the early mornings. Paperboy jobs were highly valued as a source of extra pocket money, but the paper rounds were usually quite big and widespread because most people would buy their newspapers on the way to work. It was unusual to see a girl doing a paper round.

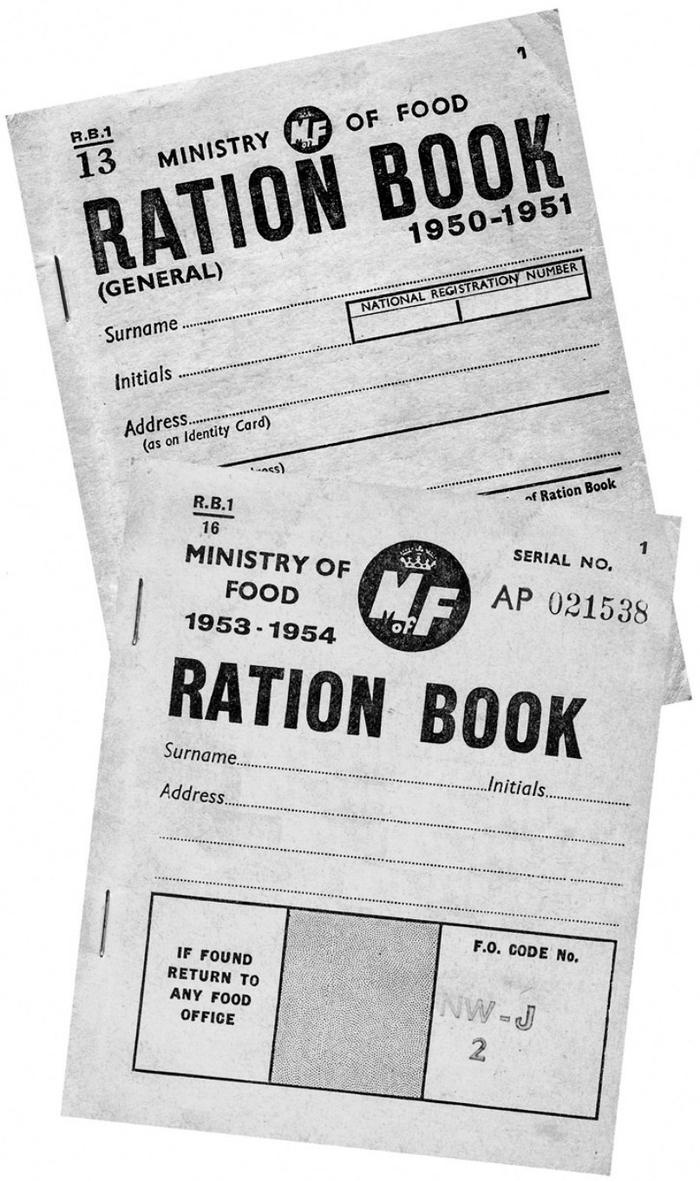

Food ration books issued by the Ministry of Food. Rationing of foodstuffs finally ended in July 1954.

Most homes had a few basic medical supplies on hand to treat the little warriors’ cuts and grazes, fevers or infections. Aspirin, Beecham’s Powders, Veno’s cough mixture (at least a year old), a bottle of smelling salts, a tin of plasters, tincture of iodine antiseptic, and Germolene antiseptic cream with its distinctive hospital smell that reassured you of its remedial powers.

As a young child in the early 1950s, you ate quite healthily with high calcium and iron intakes through eating foods like bread and milk, red meat, greens and potatoes, and you drank very few sugary drinks. You were also very fit with all those exhausting and dangerous games you played, but you still couldn’t escape the childhood illnesses. Chicken Pox, Measles, Whooping Cough, German Measles, Mumps and Tonsillitis; you got them all. In the early 1950s, before immunisation started in 1955, there was a great fear of catching polio. It was a horrible disease that crippled thousands of children and, sadly, killed many. It wasn’t unusual to see children with crutches, leg callipers or corrective shoes after contracting polio. Diphtheria was a big killer prior to the introduction of nationwide immunisation in the 1940s, which resulted in a dramatic fall in the number of reported cases. In 1940, there were 3,283 deaths in the UK, compared with just six deaths from the disease in 1957. Tuberculosis (TB) was also a big concern in Britain up until the BCG vaccination was introduced in 1953; but even then TB didn’t disappear entirely.

Winter always brought the misery of colds and flu, and minor infections like earache were common, as were

involuntary nosebleeds and fight-inflicted bloody noses. The walking wounded were to be seen everywhere; a child with his or her arm or leg in plaster, a temporary eye patch, or a leather fingerstall tied around the wrist, were all familiar sights.

If you needed to see the doctor, it seemed easy. You didn’t have to make an appointment; you just turned up at the surgery and waited your turn. Doctors’ waiting rooms were small intimate places, simply furnished with rows of hardback wooden chairs. There was no receptionist to manage the patients and doctors would retrieve patients’ notes from filing cabinets themselves. Apart from the wooden chairs, the only accessory in the waiting room was the bell or buzzer to summon the next patient into the surgery. Doctors did a lot of home visits; if your mum said you were ill in bed, the doctor came out without any fuss. It all seemed very efficient and free of paperwork. In the early 1950s, you definitely didn’t want to hear the doctor say that you needed an injection. They were still using re-usable needles then, and they were so big! The doctor would ask your mum to boil the needle in a saucepan of water for a few minutes to sterilise it. That would add to the trauma, with so much more time for the patient to think about it. The injections made a huge hole in the fleshy part of your tiny arm or backside, and they really hurt.

If you were confined to bed with some dreaded lurgy, then you had to have a bottle of Lucozade and a bunch of grapes next to the bed, even if you didn’t like grapes. The Lucozade was supposed to give you energy and most kids loved it. You had to drink it while you could because it was expensive and was only bought when someone was ill.

Although we had free healthcare under the newly created National Health Service (established 1948), from 1952 it cost your mum a shilling to get a doctor’s prescription form filled in at the chemist, and this charge was increased to one shilling per item in 1956.

There was also a charge of

£

1 introduced for dental treatment in 1952. No child of the ’50s will ever forget the dreaded visits to the dentist. It was the stuff of nightmares! That horrible cube of dry wadding that the dentist would shove under your back teeth to keep your mouth open, and the awful smell of the black rubber face-mask that was held over your nose and mouth to administer the anaesthetic gas that would send you to sleep and into a world of hallucinatory nightmarish dreams. Afterwards, you drifted back into consciousness tasting the disgusting mix of bleeding gums and residual gas in your mouth, and the nausea inevitably brought on bouts of uncontrollable vomiting. The horrendous experience didn’t end at the dentist’s door because the soreness, nausea and dizziness could last for several hours. Who could question why a child of the ’50s would often need to be dragged screaming and shouting to the dentist’s chair?

Any child that was hospitalised in the 1950s will remember the Nightingale wards, named after Florence Nightingale, with rows of beds each side of a long room and large tables in the middle where the nurses did their paperwork and held meetings. The nurses were always so clean and smart in their uniforms, with white starched bib-front pinafore dresses and caps, and blue elasticated belts with a crest on the buckle. Most had an upside-down watch pinned to the top of their pinafore for use when they checked patients’

pulses. Was there ever a boy with a slow pulse reading? Most young girls wanted to be a nurse and the boys wanted to marry one! The smell of ether was ever present throughout hospital buildings, but if you were an inpatient you soon got used to it. For young kids, hospitals were lonely places and you could feel abandoned. You were often placed in adult wards and up until 1954, children in hospital were only allowed to see their parents on Saturdays and Sundays, and only for a short time. The hospitals were run very formally, with Matron’s daily inspections sending every nurse into a panic, but you were very well looked after, and the doctors and nurses were wonderful.

There you are, out in the street wearing your new Davy Crockett fur hat and a belt with double holsters strapped to your legs, looking down the barrel of a Roy Rogers silver six-shooter cap-gun, and you have just run out of caps for your Wyatt Earp style long barrel shotgun. Nothing for it but to run home and get your spud-gun and one of mums big baking potatoes for ammunition.

‘Come on, get out of that bed, it’s eight o’clock and you can’t lie there all day!’ Blimey, you can’t even get a lie-in on a Saturday morning! You turn over and curl up again for another minute’s shut-eye while you try to pick up the threads of your broken dream. No, you haven’t really got the latest six-shooter cap-gun with matching holsters, but you’ve seen one in your local Woolworths store and you dream of having it, along with all the other trappings of your big-screen cowboy heroes. You have got a Davy

Crockett fur hat that your mum made for you, but sadly, your cowboy adventures are usually played out with guns and rifles made from sticks and lumps of wood that you have whittled into shape with your penknife, and the sound effects are just primitive ‘bang-bangs’ that you shout as you aim your deadly weapon at the escaping bandits.

‘Come on, get out of that bed, it’s a quarter past eight and your mates will be knocking for you soon!’ Yes, I must get up or I’ll be late for Saturday Morning Pictures at the Odeon!

If you lived in, or near to, a town in the 1950s then the highlight of your week was Saturday Morning Pictures at the local cinema

.

Other than that, weather permitting, most of your spare time would have been spent outside enjoying the thrills and spills of childhood.

Many towns and cities across the country were badly damaged during the Second World War ‘Blitz’ bombing by Nazi Germany, with over a million houses destroyed or damaged in London alone. More than a decade later the evidence was still clear to see, with dilapidated houses and bomb ruins everywhere. These, together with derelict land created through the post-war slum clearance programmes, became the forbidden playgrounds of the post-war baby boomers. The local council housing estates and tenement buildings usually had their own concrete playgrounds or play areas, but these were characterless places, and local kids would usually venture out onto the streets to find adventure and mischief away from prying eyes. The local parks had children’s play areas or ‘swing gardens’, as they were called. These always had a park keeper or warden dressed in full uniform with a peaked cap. The

park keepers, who often walked with a limp from an old war injury and were cruelly mimicked by the kids, would officiate in military style and it wouldn’t be long before someone was being thrown out of the park for messing around on the equipment.

A busy children’s playground in Ayr in 1954, with lots of children playing on all sorts of equipment, including a roundabout, swings and slides.

There were certain places that you would go to play depending on what you were planning to do. A derelict house used for a game of swashbuckling pirates would act as your ship, and the local woods might either be your jungle for playing Tarzan or your forest for playing Robin Hood.

Sometimes, you gave these places special code names; the alleyway for a game of Tin Tan Tommy would be called Tin Can Alley, a fenced-in bomb ruin used for a game of cowboys and Indians might be The Fort, and an old air-raid shelter used to plan the next adventure could be The Hideout. Many of the games and escapades were handed down from elder siblings, but time spent on the streets stimulated the imagination of younger siblings and they would often adapt an old idea to create a new game. Kids often had their own set of rules and values without really knowing it; word would get around about the places that were really dangerous to go to, or areas that you should only go to in a group. Gangs were just a group of kids that played together. There were no territorial divides and newcomers were always welcome to join in. Most kids were very streetwise and would steer clear of adults they didn’t know. You knew all the comings and goings in the neighbourhood, and even how to avoid the local Bobbies on their beats. You were also very fit and could run away from trouble! Policemen were respected and feared; you might give them a bit of cheek from a safe distance but if you got caught then you would get a clip around the ear. You wouldn’t dare tell your dad because he was likely to give you another wallop for having been up to mischief and for getting into trouble with the police.

Spring and summer were great because of the mild weather, long days and light evenings. A single day could encompass a great number of activities. Nothing was planned for; what you did was dependent upon who was around. If someone had a ball, it would only take seconds to start a game of football in the middle of the road, with

jumpers for goalposts. A game could start with just two kids and end with fifteen. There were no rules; kids would just join in as they arrived in the street, but the game would always belong to the owner of the ball. If he got injured or threw a tantrum then it was likely that he would take his ball home and the game would end. Girls would often gather on the pavements to watch and shout encouragement, and the bravest of these would even attempt a kick or two of the ball.

Pushbikes were a luxury and so it was only the lucky few that had them. However, there was always the desire to have ‘wheels’ and much fun was had on home-made wooden go-karts, made out of old crates, lumps of wood and discarded pram wheels. You fixed an upright stick to the side, which you pulled back to scrape against the wheel and act as a brake, and there was a piece of rope tied to the front axle for steering. In winter, if you had snow, you would turn your hand to making wooden sledges and head for the nearest hill.

If you were bored, you could always go spotting car number plates on the main road, and wonder at some of the strange place names sign-written on the side of lorries. Then there were the train-spotting anoraks that would head off to the local railway station on a weekend with fish-paste sandwiches and a flask. But if that wasn’t your idea of fun, as long as there was someone around for you to play with you rarely got bored. There were hundreds of different games you could play in any available location

.

You were fortunate if your mum and dad gave you your own pocket money to spend on whatever you wanted. Money was scarce and most kids got just enough to buy a few sweets and a comic. If you got a shilling a week then you were lucky; the

Beano

and

Dandy

cost tuppence each, and by the time you bought a few sweets you weren’t left with much to do anything else. You didn’t really need a lot because most of your free time was spent playing games or hanging-out with your mates, but sometimes, particularly during the holidays, you did need money for bus fares, or to get into the pictures or to go swimming. Fortunately, there was no peer pressure on kids to have the latest toy or to wear certain clothes, or anything like that. You could always bunk in to the pictures but usually you got caught and chucked out. Sometimes, one or two of you might get let in through one of the side exit doors by a mate on the inside who had already paid, but it was risky because you would all get chucked out if you were caught, so mostly you paid.

This was the money we were using in the 1950s, long before Britain went decimal. The picture shows an old pound note, ten-shilling note, and all of the old coins, including a farthing, halfpenny, penny, three-penny piece, sixpence, shilling, two shilling or florin, and a half-crown.

Enterprising kids found legitimate ways to earn extra money, but there was a lot of competition for anything money-earning. The newspaper rounds at the local newsagents were snapped up very quickly. Kids would team up to knock on doors and ask for any old newspapers, cardboard, rags and metal, and take them in an old pram or homemade cart to the scrap yard to be weighed and exchanged for cash. You could only do this every few weeks because it would take people time to acquire more of the same unwanted stuff in their houses. Neighbours never had a problem in getting something they had forgotten at the

shops, usually a packet of fags (cigarettes), because there was always an eager child ready to run errands for a couple of pennies. Collecting beer and lemonade bottles was a real money-spinner! When beer and fizzy drinks were sold, the price included a deposit of between one and three-pence on the bottle to get people to take the empties back for reprocessing, but many people discarded the bottles, much to the joy of little mercenaries. Quart bottles of beer were the most profitable: sometimes you could nip into the yard at the back of the pub, pick up a couple of empties and return them to a pub down the road that was owned by the same brewery. Kids learned from a young age that when adults drank alcohol, it not only loosened their tongues but it also made them more generous with their cash. On a Saturday or Sunday lunchtime, you could sit on the doorstep of the local pub with one or two of your mates, all looking dejected, and it wouldn’t be long before one of the neighbours would emerge from the pub with lemonade and crisps for all. Remember those old Smith’s potato crisp packets? You always had to rummage around to find the blue twist wrapper of salt at the bottom of the bag? There were no flavoured crisps back then; we had to wait until 1961 before we could experience the first taste of flavoured crisps, which was chicken. Then there were the long narrow 2d packets of KP nuts; pitiful when compared to the huge packs of peanuts sold in the shops today.

In the summer, lots of local corner pubs had their annual pub beanos, when regulars took a coach or charabanc daytrip to the nearest seaside resort. The coach would be stocked with crates of beer and everyone would be in a good mood. All the local kids would gather around for the

traditional ‘coin chucking’, which involved the occupants of the coach throwing any loose change they had out of the coach windows as the coach pulled away. It was mostly ‘coppers’ that they threw but there was always some silver coins. As the coach moved off, there was a mad scramble in the road to collect as many coins as possible.

Kids did all sorts of unofficial work to get extra pocket money, like helping local shopkeepers and tradesmen; and of course the local milkman usually had a little helper. This was all slave labour, but kids had loads of energy and didn’t understand the true value of the work they did. If you could earn sixpence down the market for moving a few boxes then that’s what you did! In winter, kids even pooled their money to buy coal from the local coal merchant and then sold it door-to-door from an old pram or pushcart. Unfortunately, there was no money to be earned out of babysitting. With so many large families around, there wasn’t much call for paid babysitters. There was always an elder sibling to look after the baby, or a neighbour would do it for nothing.

To manage your pocket money you first needed to learn the complicated calculations of pounds, shillings and pence. Most kids picked this up quickly from a very young age, and even had a reasonable understanding of the pre–1954 ration books. The coins and notes that we all used in the 1950s have been referred to as ‘old money’ since decimalisation took place in 1971. The ‘old money’ was written down using the LSD symbols

£

s d, which were abbreviations for ‘pounds, shillings and pence’. An example of how it was written would be

£

4 3s 6d (four pounds, three shillings, and six pence, or four pounds three-and-six). The ‘

£

’ symbol was used for the pound and comes from the Latin word

librum

(a Roman unit of weight derived from the Latin word for ‘scales’). The ‘s’ symbol was used for the shilling and comes from the Latin word

solidus

(a Roman gold coin derived from the Latin word for ‘whole’). The ‘d’ symbol was used for pence and comes from the Latin word

denarius

(a common Roman coin). There were some peculiarities about the way we used and spoke about money. Sometimes, expensive items would be sold in units of one guinea, which was equal to twenty-one shillings, but the coin itself no longer existed in the 1950s – in fact, the guinea coin had not been struck since 1799. Money was often referred to by slang names such as brass, dosh, dough, folding stuff, lolly, moola or readies. A group of farthings, halfpennies and pennies were called ‘coppers’, meaning a small amount of money as in ‘just a few coppers’. Something costing one and a half pennies would be called ‘threehaypence’ or ‘threehaypenny worth’, as in ‘three halfpennies’. It was quite normal for a shop to only use shillings and pence when pricing up low-value goods, so a pair of shoes might be advertised at 49/11d rather than

£

2 9s 11d. There was no two pence coin but the words ‘tuppence’ or ‘tuppenny’ were regularly used by everyone. Money would sometimes be used to describe people, as in the term ‘not quite the full shilling’.