90 Minutes in Heaven (7 page)

When Dr. Greider examined me, he faced a choice. He could use the Ilizarov frame or amputate. Even if he chose to use the Ilizarov frame, there was no guarantee that I would not lose the leg. In fact, at that stage, he wasn’t even certain I would pull through the ordeal. A less-skilled and less-committed doctor might have amputated, assuming it wouldn’t make much difference because I would die anyway.

Fifth, people prayed for me. I have thousands of cards, letters, and prayer-grams, many from people I don’t know in places I’ve never been who prayed for me because they heard of the accident. I’ve since had people tell me that this experience changed their prayer lives and their belief in the power of prayer.

On the night I entered Hermann Trauma Center, I was in surgery for eleven hours. During that operation, I had the broken bone in my right leg set. My left forearm had to be stabilized because two inches of each bone were missing. My left leg was put into traction because four and a half inches of femur were missing. During the operation, an air tube was mistakenly inserted into my stomach. This caused my stomach to inflate and my lungs to deflate. It would be several days before they discovered that this was the cause of the swelling in my stomach. Further complicating my breathing, I was unable to be elevated, and I developed pneumonia. I nearly died a second time.

Because of many bruises and the severity of my obvious wounds, my doctors hardly knew where to start. Other less serious problems became obvious weeks later. Several years passed before they discovered a fractured pelvis that they had missed initially.

I lay on my bed with needles everywhere, unable to move, dependent on the life-support apparatus. I could barely see over the top of my oxygen mask. During most of those days in the ICU, I was in and out of consciousness. Sometimes I’d wake up and see people standing in front of my bed and would wonder,

Am I really here or am I just imagining this?

Monitors surrounded me, and a pulse oximeter on my finger tracked my oxygen level. Because I wasn’t getting enough oxygen, the alarm went off often, bringing nurses racing into my room.

The ICU in Hermann is near the helipad; helicopters took off and landed at all hours of the day. When I was awake, I felt as if I were in a Vietnam movie. There were no clocks in the room, so I had no concept of time.

Other people lay in beds near me, often separated by nothing more than a curtain. More than once I awakened and saw orderlies carrying out a stretcher with a sheet over the body. As a pastor, I knew that many people don’t leave the ICU alive.

Am I next?

I’d ask myself.

Although I asked the question, the pain prevented my caring. I just wanted not to hurt, and dying would be a quick answer.

I had experienced heaven, returned to earth, and then suffered through the closest thing to hell on earth I ever want to face. It would be a long time before my condition or my attitude changed.

Nightmarish sounds filled the days and the nights. Moans, groans, yells, and screams frequently disrupted my rest and jerked me to consciousness. A nurse would come to my bed and ask, “Can I help you?”

“What are you talking about?” I’d ask. Sometimes I’d just stare at her, unable to understand why she was asking.

“You sounded like you’re in great pain.”

I am,

I’d think, and then I’d ask, “How would you know that?”

“You cried out.”

That’s when I realized that sometimes the screams I heard came from me. Those groans or yells erupted when I did something as simple as trying to move my hand or my leg. Living in the ICU was horrible. They were doing the best they could, but the pain never let up.

“God, is this what I came back for?” I cried out many times. “You brought me back to earth for this?”

My condition continued to deteriorate. I had to lie flat on my back because of the missing bone in my left leg. (They never found the bone. Apparently, it was ejected from the car into the lake when my leg was crushed between the car seat and dash-board.) Because of having to lie flat, my lungs filled with fluid. Still not realizing my lungs were collapsed, nurses and respiratory therapists tried to force me to breathe into a large plastic breathing device called a spirometer to improve my lung capacity.

On my sixth day, I was so near death that the hospital called my family to come to see me. I had developed double pneumonia, and they didn’t think I would make it through the night.

I had survived the injuries; now I was dying of pneumonia.

My doctor talked to Eva.

“We’re going to have to do something,” he told her. “We’re either going to have to remove the leg or do something else drastic.”

“How drastic?”

“If we don’t do something, your husband won’t be alive in the morning.”

That’s when the miracle of prayer really began to work. Hundreds of people had been praying for me since they learned of the accident, and I knew that. Yet, at that point, nothing had seemed to make any difference.

Eva called my best friend, David Gentiles, a pastor in San Antonio. “Please, come and see Don. He needs you,” she said.

Without any hesitation, my friend canceled everything and jumped into his car. He drove nearly two hundred miles to see me. The nursing staff allowed him into my room in ICU for only five minutes.

Those minutes changed my life.

I never made this decision consciously, but as I lay there with little hope of recovery—no one had suggested I’d ever be normal again—I didn’t want to live. Not only did I face the ordeal of never-lessening pain but I had been to heaven. I wanted to return to that glorious place of perfection. “Take me back, God,” I prayed, “please take me back.”

Memories filled my mind, and I yearned to stand at that gate once again. “Please, God.”

God’s answer to that prayer was “no.”

When David entered my room, I was disoriented from the pain and the medication. I was so out of it that first I had to establish in my mind that he was real.

Am I hallucinating this?

I asked myself.

Just then, David took my fingers, and I felt his touch. Yes, he was real.

He clasped my fingers because that was all he could hold. I had so many IVs that my veins had collapsed; I had a trunk line that went into my chest and directly to my heart. I used to think of my many IVs as soldiers lined up. I even had IVs in the veins in the tops of my feet. I could look down and see them and realize they’d put needles in my feet because there was no place left on my body.

“You’re going to make it,” David said. “You have to make it. You’ve made it this far.”

“I don’t have to make it. I’m not sure . . . I . . . I don’t know if I want to make it.”

“You have to. If not for yourself, then hold on for us.”

“I’m out of gas,” I said. “I’ve done all I can. I’ve given it all I can. I don’t have anything else to give.” I paused and took several breaths, because even to say two sentences sapped an immense amount of energy.

“You have to make it. We won’t let you go.”

“If I make it, it’ll be because all of you want it. I don’t want it. I’m tired. I’ve fought all I can and I’m ready to die.”

“Well, then you won’t have to do a thing. We’ll do it for you.”

Uncomprehending, I stared at the intensity on his face.

“We won’t let you die. You understand that, Don? We won’t let you give up.”

“Just let me go—”

“No. You’re going to live. Do you hear that? You’re going to live. We won’t let you die.”

“If I live,” I finally said, “it’ll be because you want me to.”

“We’re going to pray,” he said. Of course, I knew people had been praying already, but he added, “We’re going to pray all night. I’m going to call everybody I know who can pray. I want you to know that those of us who care for you are going to stay up all night in prayer for you.”

“Okay.”

“We’re going to do this for you, Don. You don’t have to do anything.”

I really didn’t care whether they prayed or not. I hurt too badly; I didn’t want to live.

“We’re taking over from here. You don’t have to do a thing—not a thing—to survive. All you have to do is just lie there and let it happen. We’re going to pray you through this.”

He spoke quietly to me for what was probably a minute or two. I don’t think I said anything more. The pain intensified—if that was possible—and I couldn’t focus on anything else he said.

“We’re going to take care of this.” David kissed me on the forehead and left.

An all-night prayer vigil ensued. That vigil marked a turning point in my treatment and another series of miracles.

The pneumonia was gone the next day. They prayed it away. And the medical staff discovered the error with the breathing tube.

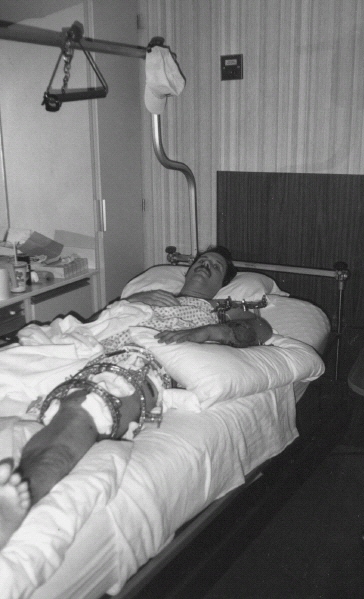

On that seventh day, in another long surgery, Dr. Greider installed the Ilizarov device so that I could sit up and receive

Don wearing the Ilizarov bone growth device.

breathing treatments. They also deflated my stomach, which allowed my lungs to inflate.

Normally, hospitals require six months of counseling before they will authorize the use of the Ilizarov frame. In my case, the medical staff could give Eva no guarantee that the experimental procedure would work. They also told her that using the Ilizarov frame would cause me considerable physical pain as well as extraordinary emotional and psychological distress. Worse, they warned that even after going through all of that, I might still lose my leg.

“This is extremely painful and takes months—maybe years—to recover,” the surgeon said to Eva. Again he reminded her of the worst that could happen—that I might still lose the leg. “However, if we don’t go this route, we have no choice but to amputate.”

He quietly explained that if they amputated they would fit me with a prosthesis, and I’d have to learn to walk with it.

Eva had no illusions about the extent of my injury or how long I would have to endure excruciating pain. She debated the pros and cons for several minutes and prayed silently for guidance. “I’ll sign the consent form,” she finally said.

The next morning, when I awakened after another twelve hours of surgery, I stared at what looked like a huge bulge under the covers where my left leg had been. When I uncovered myself, what I saw took my breath away. On my left leg was a massive stainless steel halo from my hip to just below my knee. A nurse came in and started moving around, doing things around my leg, but I wasn’t sure what she did.

I became aware of Eva sitting next to my bed. “What is that?” I asked. “What’s she doing?”

“We need to talk about it,” she said. “It’s what I agreed to yesterday. It’s a bone-growth device. We call it a fixator. It’s the only chance for the doctors to save your left leg,” she said. “I believe it’s worth the risk.”

I’m not sure I even responded. What was there to say? She had made the best decision she could and had been forced to make it alone.

Just then, I spotted wires leading from the device. “Are those wires going through my leg?”

“Yes.”

I shook my head uncomprehendingly. “They’re going

through

my leg?”

“It’s a new technique. They’re trying to save your leg.”

I didn’t know enough to comment. I nodded and tried to relax.

“I believe it will work,” she said.

I hoped she was right. Little did I know that nearly a year later I would still be staring at it.

Can anyone ever separate us from Christ’s love? Does it mean he no longer loves us if we have trouble or calamity, or are persecuted, or are hungry or cold or in danger or threatened with death? (Even the Scriptures say, “For your sake we are being killed every day; we are being slaughtered like sheep.”)

R

OMANS 8:35–36

O

ne of the most difficult things for me—aside from my own physical pain—was to see the reaction of my family members and close friends. My parents live in Louisiana, about 250 miles from Houston, but they arrived the day after my first surgery. My mother is a strong woman, and I always thought she could handle anything. But she walked into the ICU, stared at me, and then crumpled in a faint. Dad had to grab her and carry her out.