60 Classic Australian Poems for Children (2 page)

Read 60 Classic Australian Poems for Children Online

Authors: Cheng & Rogers

The Ant Explorer

CJ Dennis

Once a little sugar ant made up his mind to roamâ

To fare away far away, far away from home.

He had eaten all his breakfast, and he had his Ma's consent

To see what he should chance to see; and here's the way he wentâ

Up and down a fern frond, round and round a stone,

Down a gloomy gully where he loathed to be alone,

Up a mighty mountain range, seven inches high,

Through the fearful forest grass that nearly hid the sky,

Out along a bracken bridge, bending in the moss,

Till he reached a dreadful desert that was feet and feet across.

'Twas a dry, deserted desert, and a trackless land to tread;

He wished that he was home again and tucked-up tight in bed.

His little legs were wobbly, his strength was nearly spent,

And so he turned around again; and here's the way he wentâ

Back away from desert lands, feet and feet across,

Back along the bracken bridge bending in the moss,

Through the fearful forest grass, shutting out the sky,

Up a mighty mountain range seven inches high,

Down a gloomy gully, where he loathed to be alone,

Up and down a fern frond and round and round a stone.

A dreary ant, a weary ant, resolved no more to roam,

He staggered up the garden path and popped back home.

A Book for Kids

, 1921

The Australian Slanguage

WT Goodge

'Tis the everyday Australian

Has a language of his own,

Has a language, or a slanguage,

Which can simply stand alone;

And a âdickon pitch to kid us'

Is a synonym for âlie,'

And to ânark it' means to stop it,

And to ânit it' means to fly.

And a bosom friend's a âcobber,'

And a horse a âprad' or âmoke,'

While a casual acquaintance

Is a âjoker' or a âbloke.'

And his lady-love's his âdonah'

Or his âclinah' or his âtart'

Or his âlittle bit o' muslin,'

As it used to be his âbart.'

And his naming of the coinage

Is a mystery to some,

With his âquid' and âhalf-a-caser'

And his âdeener' and his âscrum!'

And a âtin-back' is a party

Who's remarkable for luck,

And his food is called his âtucker'

Or his âpanem' or his âchuck.'

A policeman is a âjohnny'

Or a âcopman' or a âtrap,'

And a thing obtained on credit

Is invariably âstrap.'

A conviction's known as âtrouble,'

And a gaol is called a âjug,'

And a sharper is a âspieler,'

And a simpleton's a âtug.'

If he hits a man in fighting

That is what he calls a âplug,'

If he borrows money from you

He will say he âbit your lug.'

And to âshake it' is to steal it,

And to âstrike it' is to beg,

And a jest is âpoking borac'

And a jester âpulls your leg.'

Things are âcronk' when they go wrongly

In the language of the âpush,'

But when things go as he wants 'em

He declares it is âall cush.'

When he's bright he's got a ânapper,'

And he's âratty' when he's daft,

And when looking for employment

He is âout o' blooming graft.'

And his clothes he calls his âclobber'

Or his âtogs', but what of that

When a âcastor' or a âkady'

Is the name he gives his hat!

And our undiluted English

Is a fad to which we cling,

But the great Australian slanguage

Is a truly awful thing!

The Bulletin

, 1898

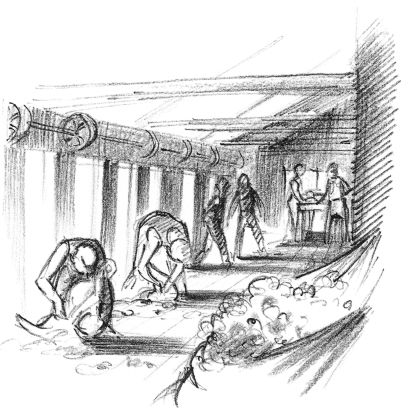

The bell is set a-ringing and the engine gives a toot,

There's five-and-thirty shearers here are shearing for the loot,

So stir yourselves, you penners-up, and shove the sheep along,

The musterers are fetching them a hundred-thousand strong;

And make your collie dogs speak upâwhat

would

the buyers say

In London if the wool was late this year from Castlereagh!

The man that rang the Tubbo shed is not the ringer here,

That stripling from the Cooma side can teach him how to shear;

They trim away the ragged locksâand

rip

the cutter goes

And leaves a track of snowy wool from brisket to the nose.

It's lovely how they peel it off with never stop nor stayâ

They're racing for the ringer's place this year at Castlereagh.

The man that keeps the cutters sharp is growling in his cage,

He's always in a hurry and he's always in a rage.

âYou clumsy-fisted mutton-heads, you'd make a fellow sick,

You

pass yourselves as shearersâyou were born to swing a pick;

Another broken cutter here, that's two you've broke to-dayâ

It's awful how such crawlers come to shear at Castlereagh.'

The youngsters picking up the fleece enjoy the merry din

They throw the classer up the fleece, he throws it to the bin.

The pressers standing in their box are waiting for the wool,

There's room for just a couple more, the press is nearly full.

Now jump upon the lever, lads, and heave and heave away,

Another bale of snowy fleece is branded âCastlereagh.'

From South and East the shearers come across the Overland,

Upon the slopes of Southern hills their little homesteads stand,

And all day long with desperate haste they're shearing for their lives,

The cheque they earn at Castlereagh brings comfort to their wives.

So may each shearer tally up a hundred sheep a day,

And every year obtain a shed as good as Castlereagh.

The Bulletin

, 1894

Bell-birds

Henry Kendall

By channels of coolness the echoes are calling,

And down the dim gorges I hear the creek falling;

It lives in the mountain, where moss and the sedges

Touch with their beauty the banks and the ledges;

Through brakes of the cedar and sycamore bowers

Struggles the light that is love to the flowers.

And, softer than slumber, and sweeter than singing,

The notes of the bell-birds are running and ringing.

The silver-voiced bell-birds, the darlings of day-time,

They sing in September their songs of the May-time.

When shadows wax strong, and the thunder-bolts hurtle,

They hide with their fear in the leaves of the myrtle;

When rain and the sunbeams shine mingled together

They start up like fairies that follow fair weather,

And straightway the hues of their feathers unfolden

Are the green and the purple, the blue and the golden.

October, the maiden of bright yellow tresses,

Loiters for love in these cool wildernesses;

Loiters knee-deep in the grasses, to listen,

Where dripping rocks gleam and the leafy pools glisten.

Then is the time when the watermoons splendid

Break with their gold, and are scattered or blended

Over the creeks, till the woodlands have warning

Of songs of the bell-bird and wings of the morning.

The first four lines of stanza four were printed in the

Australian Town and Country Journal

on 26 January 1889.

Welcome as waters unkissed by the summers,

Are the voices of bell-birds to thirsty far-comers.

When fiery December sets foot in the forest,

And the need of the wayfarer presses the sorest,

Pent in the ridges for ever and ever,

The bell-birds direct him to spring and to river,

With ring and with ripple, like runnels whose torrents

Are toned by the pebbles and leaves in the currents.

Often I sit, looking back to a childhood

Mixt with the sights and the sounds of the wildwood,

Longing for power and the sweetness to fashion

Lyrics with beats like the heart-beats of passionâ

Songs interwoven of lights and of laughters

Borrowed from bell-birds in far forest-rafters;

So I might keep in the city and alleys

The beauty and strength of the deep mountain valleys,

Charming to slumber the pain of my losses

With glimpses of creeks and a vision of mosses.

Poems of Henry Kendall

, 1886

Brumby's Run

Banjo Paterson

[

The Aboriginal term for a wild horse is âBrumby.'

At a recent trial in Sydney a Supreme Court Judge,

hearing of âBrumby horses', asked: âWho is Brumby, and

where is his Run?'

]

It lies beyond the Western Pines

Towards the sinking sun,

And not a survey mark defines

The bounds of âBrumby's run.'

On odds and ends of mountain land,

On tracks of range and rock,

Where no one else can make a stand,

Old Brumby rears his stockâ

A wild, unhandled lot they are

Of every shape and breed.

They venture out 'neath moon and star

Along the flats to feed;

But when the dawn makes pink the sky

And steals along the plain,

The Brumby horses turn and fly

Towards the hills again.

The traveller by the mountain-track

May hear their hoof-beats pass,

And catch a glimpse of brown and black

Dim shadows on the grass.

The eager stockhorse pricks his ears

And lifts his head on high

In wild excitement when he hears

The Brumby mob go by.

Old Brumby asks no price or fee

O'er all his wide domains:

The man who yards his stock is free

To keep them for his pains.

So, off to scour the mountain-side

With eager eyes aglow,

To strongholds where the wild mobs hide

The gully-rakers go.

A rush of horses through the trees,

A red shirt making play;

A sound of stockwhips on the breeze,

They vanish far away!

Ah, me! before our day is done

We long with bitter pain

To ride once more on Brumby's run

And yard his mob again.

The Bulletin

, 1895