44 Scotland Street (41 page)

Read 44 Scotland Street Online

Authors: Alexander McCall Smith

Tags: #Mystery, #Adult, #Contemporary, #Humour

That morning, as Dr Fairbairn ushered them into his consulting room, she noticed that there was a new copy of the

International Bulletin of Dynamic Psychoanalysis

lying on the top of his desk. The sight thrilled her, and she tried, by craning her neck, to make out the titles listed on the cover.

Mother as Stalin

, she read,

A New Analysis

. That looked interesting, even if the title was slightly opaque. It must have been all about the need that boys are said to feel to get away from the influence of their mothers. Yes, she supposed that this was true: there were boys who needed to get away from their mothers, but that was certainly not Bertie’s problem. She had a perfectly good relationship with Bertie, as Dr Fairbairn was no doubt in the process of discovering. Bertie’s problem was … well, she was not sure what Bertie’s problem was. Again, this was something that Dr Fairbairn would illuminate over the weeks and months to come. It was, no doubt, his anxieties over the good breast and what she had always referred to as Bertie’s

additional part

. Boys tended to be anxious about their additional parts, which was strange, as she would have imagined an additional part was something to which one might reasonably be quite indifferent, in the same way one was indifferent to other appendices, such as one’s appendix.

And then there was another, quite fascinating article:

Marian

Apparitions in Immediate Post War Italy: Popular Hysteria and the

Virgin as Christian Democrat

. That looked very interesting indeed; perhaps she could ask Dr Fairbairn whether she could borrow that once he had read it. The Virgin tended to appear in all sorts of places and at all sorts of times, but there was sometimes a question mark over those who saw her. Rome urged caution in such cases, as did Vienna …

Bertie sat down next to Dr Fairbairn’s desk while Irene sat on a chair against the wall, where Bertie could not see her while he was talking to the psychotherapist.

“How do you feel today, Bertie?” asked Dr Fairbairn. “Are you feeling happy? Are you feeling angry?”

Bertie stared at Dr Fairbairn. He noticed that the tie he was wearing had a small teddy-bear motif woven into it. Why, he wondered, would Dr Fairbairn wear a teddy-bear tie? Did he still play with teddy-bears? Bertie had noticed that some adults were strange that way; they hung on to their teddy bears. He had a teddy bear, but he was no longer playing with him. It was not that he was punishing him, nor that his teddy bear, curiously, had no additional part; it was just that he no longer liked his bear, who smelled slightly of sick after an unfortunate incident some months previously. That was all there was to it – nothing more.

“Do you like teddy bears, Dr Fairbairn?” asked Bertie. “You have teddy bears on your tie.”

Dr Fairbairn smiled. “You’re very observant, Bertie. Yes, this is a rather amusing tie, isn’t it? And do I like teddy bears? Well, I suppose I do. Most people think of teddy bears as being rather attractive, cuddly creatures.” He paused. “Do you know that song about teddy bears, Bertie?”

“

The Teddy Bears’ Picnic

?”

“Exactly. Do you know the words for it, Bertie?”

Bertie thought for a moment. “

If you go down to the woods

today

…”

“Y

ou’re sure of a big surprise!

” continued Dr Fairbairn. “

If you

go down to the woods today/ You’d better go in disguise

. And so on. It’s a nice song, isn’t it Bertie?”

“Yes,” said Bertie. “But it’s a bit sad, too, isn’t it?”

Dr Fairbairn leaned forward. This was interesting. “Sad, Bertie? Why is

The Teddy Bears’ Picnic

sad?”

“Because some of the teddy bears will not get a treat,” said Bertie. “Only those who have been good. That’s what the song says.

Every bear who’s ever been good/ Is sure of a treat today

. What about the other bears?”

Dr Fairbairn’s eyes widened and he scribbled a note on a pad of paper before him. “They get nothing, I’m afraid. Do you think that you would get something if you went on a picnic, Bertie?”

“No,” said Bertie. “I would not. The teddy bears who set fire to their Daddies’ copies of

The Guardian

will get nothing at that picnic. Nothing at all.”

There was a silence. Then Dr Fairbairn asked another question.

“Why did you set fire to Daddy’s copy of

The Guardian

, Bertie? Did you do that because guardian is another word for parent? Was

The Guardian

your Daddy because Daddy is your guardian?”

Bertie thought for a moment. Dr Fairbairn was clearly mad, but he would have to keep talking to him; otherwise the psychotherapist might suddenly kill both him and his mother. “No,” he said. “I like Daddy. I don’t want to set fire to Daddy.”

“And do you like

The Guardian

?” pressed Dr Fairbairn.

“No,” said Bertie. “I don’t like

The Guardian

.”

“Why?” asked Dr Fairbairn.

“Because it’s always telling you what you should think,” said Bertie. “Just like Mummy.”

98. Irene and Dr Fairbairn Converse

With Bertie sent off to the waiting room where he might occupy himself with an old copy of

Scottish Field

, Irene and Dr Fairbairn shared a cup of strong coffee in the consulting room, mulling over the outcome of Bertie’s forty minutes of intense conversation with his therapist.

“That bit about teddy bears was most interesting,” said Dr Fairbairn, thoughtfully. “He had constructed all sorts of anxieties around that perfectly simple account of a bears’ picnic. Quite remarkable.”

“Very strange,” said Irene.

“And as for that exchange over

The Guardian

,” went on Dr Fairbairn. “I was astonished that he should see you as overly directional. Quite astonished.”

“Absolutely,” said Irene. “I’ve never pushed him to do anything. All his little enthusiasms, his Italian, his saxophone, are of his own choosing. I’ve merely facilitated.”

“Of course,” said Dr Fairbairn hurriedly. “I knew as much. But then children misread things so badly. But it’s certainly nothing for you to worry yourself about.”

He paused, placing his coffee cup down on its saucer. “But then that dream he spoke about was rather fascinating, wasn’t it? The one in which he saw a train going into a tunnel. That was interesting, wasn’t it?”

“Indeed,” said Irene. “But then, Bertie has always had this thing about trains. He goes on and on about them. I don’t think there’s any particular symbolism in his case – he really is dreaming about trains

qua

trains. Other boys may be dreaming about … well about other things when they dream about trains. But not Bertie.”

“But what about tunnels?” asked Dr Fairbairn.

“We have one in Scotland Street,” said Irene. “There’s a tunnel under the road. But nobody’s allowed to go into it.”

“Ah,” said Dr Fairbairn. “A forbidden tunnel! That’s very significant!”

“It’s closed,” said Irene.

“A forbidden tunnel would be,” mused Dr Fairbairn.

They both thought about this for a moment, and then Dr Fairbairn, reaching out for his cup of coffee, returned to the subject of dreams. “I have never underestimated the revelatory power of the dream,” he said. “It is the most perfect documentary of the unconscious. The film script of both the id and the ego – dancing their terrible dance, orchestrated by the sleeping mind. Don’t you think?”

“Oh, I do,” said Irene. “And do you analyse your own dreams, Dr Fairbairn?”

“Most certainly,” he replied. “May I reveal one to you?”

“But, of course.” Irene loved this. It must be so lonely being Dr Fairbairn and having so few patients – perhaps none, apart from herself – with whom he could communicate on a basis of intellectual and psychoanalytical equality.

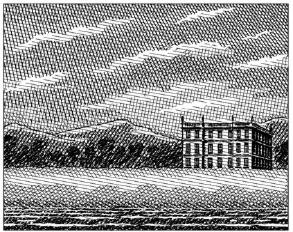

“My dream,” said Dr Fairbairn, “occurred some years ago – many years in fact, and yet my memory of it is utterly vivid. In this dream I was somewhere in the West – Argyll possibly – and staying in a large house by the edge of a sea loch. The house was a couple of hundred yards from the edge of the loch, and it was set about with grass of the most extraordinary verdant colour. And this grass was touched with the golden light, as of the morning sun.

“The woman who lived in this house had a name, unlike so many people who come to us in our dreams. She was called Mrs Macgregor – I remember that very distinctly – and she was kind to the guests. There were other people there too, but I did not know them. Mrs Macgregor was gentle and welcoming – she made a tray of tea and then took me gently by the hand and led me across the lawn to a shed beside the loch. And I can remember the smell of the air, which had that tangle of seaweed that you get in the West and that softness too. And I did not want her to let go of my hand.

“We came to the shed and she opened it for me, and do you know, there inside was a lovingly preserved art-nouveau typesetting machine. And I marvelled at this and turned round, and Mrs Macgregor was walking away from me, back towards the house, and I felt a great sense of loss. And that is when I awoke, and the house and the grass and the sea loch faded, but left me with the most extraordinary sense of peace – as if I had been vouchsafed a vision.

“Many years later, I was in a restaurant in Edinburgh, with a largish group of people after a meeting. We were sitting there waiting for our dinner to be served and the subject of dreams arose. I decided to narrate my dream, and there was a sudden hush in the restaurant. Everybody had started to listen to it – the other diners, the waiters, the Italian proprietor of the restaurant, Pasquale, as he was called – everybody.

“And there was a complete silence when I finished. Then, one of the other members of the party – a most distinguished Edinburgh psychiatrist, broke the silence. He said:

Mrs Macgregor is your mother!

“And of course Henry was right, and everybody in the restaurant started to talk again, loudly, with relief, perhaps, because they were reassured that their mothers were with them too – their mothers had not gone away.”

Irene was touched by this story, and she was silent too, as had been the diners in that restaurant. She wondered whether she dared tell Dr Fairbairn about her own dream, that had come to her only a few nights previously, in which she had been in the Floatarium, in the flotation tank, and there had been a knocking on the door, and she had opened the lid and seen a blonde child standing outside, like that figure of Cupid in the painting,

Love Locked Out

. And now she realised that BLONDE CHILD could be translated, in Scots, or half in Scots, to make FAIR BAIRN.

She could not tell him this, because this was dangerous, dangerous ground. So she closed her eyes instead, and thought

of her life. She was married to Stuart, and she was the mother of Bertie. And yet she was lonely, hopelessly lonely, because there was nobody with whom she could talk about these things that mattered so much to her. Perhaps things would change when Bertie went to the Steiner School, as he was due to do shortly. Then there would be other Steiner mothers, and she could talk to them. There would be coffee mornings and bring-and-buy sales in aid of the new personal development equipment for the school. And she would not have to go to the Floatarium and float in isolation but would be part of something bigger, and more vibrant, and accepting, as communities used to be, before our fall from grace, the shattering of our Eden.

99. Bruce Takes a Bath, and Thinks

In the bathroom of his flat at 44 Scotland Street, Bruce Anderson stood before the mirror, wearing only the white boxer shorts which his mother had given him for his last birthday. The light in the bathroom was perfect for such posing – light from a north-facing skylight which, although clear, was not too harsh. This light allowed for the development of interesting shadows – shadows which brought out the contours of the pectorals, which provided for shades and nuances in the shoulders and the sweep of the forearms.

Bruce was not unaware of his good looks. As a small boy he had become accustomed to the admiring glances which he attracted from adults. Elderly women would reach out and pat him on the head, ruffling his hair, and muttering

little angel

or

wee stunner

, and Bruce would reward them with a smile, an act of beneficence on his part which usually brought forth more exclamations from his admirers. As he became older, the women who patted his head began to desist (although they still felt the urge), as one does not pat every teenage boy on the head, no matter how strong the temptation to do so. The looks of adults were now supplemented with the wistful glances of coevals, particularly the teenage girls of Crieff, for whom Bruce seemed some sort of messenger of beauty – a sign that even in Crieff might one find a boy so transcendentally exciting that all limitations of place, all frustrations at the fact that one lived in Crieff and not in Edinburgh, or Newport Beach, or somewhere like that, might be overcome.