(4/13) Battles at Thrush Green (9 page)

Read (4/13) Battles at Thrush Green Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrush Green (Imaginary Place), #Pastoral Fiction, #Country Life - England

'Just before the war, I believe. They intended to plant a hedge between the old and new graveyards, but war interfered with the work, and in any case, the feeling was that it should all be thrown into one.'

'Would it matter?'

The rector stroked his chin thoughtfully.

'We should have to get a faculty, of course, and I've a feeling that it would be simpler if we only had the old graveyard to deal with as, obviously, they have had here. But I must go into it. I shall find out all I can as soon as we return.'

'So you like the idea?'

'Like it?' cried Charles, his face pink with enthusiasm. 'Like it? Why, I can't wait to get started!'

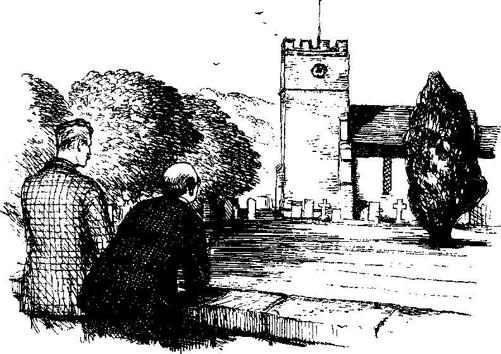

He threw his arms wide, as though he would embrace the whole beautiful scene before him.

'It's an inspiration, Harold. It's exactly what I needed to give me hope. If it can be done here, then it can be done at Thrush Green. I shall start things moving as soon as I can.'

Harold began to feel some qualms in the face of this precipitate zeal.

'We can't rush things, Charles. We must have some consultations with the village as a whole.'

'Naturally, naturally,' agreed Charles. 'But surely there can be no opposition to such a scheme?'

'I think there's every possibility of opposition.'

The rector's mouth dropped open.

'But if that is so, then I think we must bring the doubters to see this wonderful place. We could hire a coach, couldn't we? It might make a most inspiring outing –'

Harold broke in upon the rector's outpourings.

'Don't go so fast, Charles. We must sound out the parochial church council first. I must confess that I didn't think you would wax quite so enthusiastic, when I suggested this trip.'

'But why not? It's the obvious answer to our troubles. Even Piggott could keep the grass cut once the graves were levelled. A boy could! Why, even young Cooke could manage that! And we could get rid of those appalling railings at the same time as we put the stones against the wall. It's really all so simple.'

'It may seem so to you, Charles, but I think you may find quite a few battles ahead before you attain a churchyard as peaceful as this.'

Charles turned his back reluctantly upon the scene, and the two men returned to the car.

'You really must have more faith,' scolded the rector gently. 'I can't think of anyone who could have a sound reason for opposing the change.'

'Dotty Harmer might,' said Harold, letting in the clutch. 'And her hungry goats.'

'Oh, Dotty!' exclaimed Charles dismissively. 'Why bring her up?'

'Why indeed?' agreed Harold. 'Keep a look out for a decent pub.'

At that very moment, Dotty Harmer was driving into Lulling High Street.

She was marshalling her thoughts – no easy job at the best of times – but doubly difficult whilst driving. She had a parcel to post and stamps to buy. The corn merchant must be called upon to request that seven pounds of oats and the same of bran be delivered within the next week. And it might be as well to call at the ladies' outfitters to see if their plated lisle stockings had arrived.

After that, she was free to keep her luncheon engagement with the Misses Lovelock, three silver-haired old sisters whose lavender-and-old-lace exteriors hid unplumbed depths of venom and avarice. Their Georgian house fronted the main street, which gave them an excellent vantage point for noting die activities of the Lulling inhabitants. Any one of the Lovelock sisters could inform you, without hesitation, of any peccadilloes extant in the neighbourhood. Dotty looked forward to her visit.

Halfway along the High Street Dotty stopped, as she had so often done, outside the draper's, and prepared to alight. A short procession of vehicles, which had accumulated behind her slower-moving one, swerved out to pass her, the drivers muttering blasphemies under their breath. Dotty was blissfully unconscious of her unpopularity, and was about to open the door into the pathway of an unwary lorry driver, when a young policeman appeared.

'Can't stop here, ma'am,' he said politely.

'Why not?' demanded Dotty. 'I have before. Besides, I have to call at the draper's.'

'Sorry, ma'am. Double yellow lines.'

'And what, pray, do they signify?'

The young policeman drew in his breath sharply, but otherwise remained unmoved. He had had a spell of duty in the city of Oxford, and dealt daily there with eccentric academics of both sexes. He recognised Dotty as one of the same ilk.

'No parking allowed.'

'Well, it's a great nuisance. I have a luncheon engagement at that house over there.'

'Sorry, ma'am. No waiting here at all. Try the car park behind the Corn Exchange. You can leave it there safely for two or three hours.'

'Very well, very well! I suppose I must do as you say, officer. What's your name?'

'John Darwin. Four-two-four-six-nine-police-constable-stationed-at-Lulling, ma'am.'

'Darwin? Interesting. Any relation to the great Charles?'

'Not so far as I know, ma'am. No Charles'es in our lot.'

He beckoned on a line of traffic, and then bent to address Dotty once more.

'This is just a caution, ma'am. Don't park by yellow lines. Take the car straight to the car park. You'll find it's simpler for everyone.'

'Thank you, Mr Darwin. As a law-abiding citizen I shall obey you without any further delay.'

She let in the clutch, bounded forward, and vanished in a series of jerks and minor explosions round the bend to the car park.

'One born every minute,' said P.C. Darwin to himself.

The luncheon party was a great success. Bertha, Ada and Violet owned many beautiful things, some inherited, some acquired by years of genteel begging from those not well-acquainted with the predatory ladies of Lulling, and a few – a very few – bought over the years.

The meal was served on a fine drum table. The four chairs drawn up to it were of Hepplewhite design with shield backs. The silver gleamed, the linen and lace cloth was like some gigantic snowflake. Nothing could be faulted, except the food. What little there was, was passable. The sad fact was that the parsimonious Misses Lovelock never supplied enough.

Four wafer-thin slices of ham were flanked by four small sausage rolls. The sprig of parsley decorating this dish was delightfully fresh. The salad, which accompanied the meat dish, consisted of a few wisps of mustard and cress, one tomato cut into four, and half a hard-boiled egg chopped small.

For the gluttonous, there was provided another small dish, of exquisite Meissen, which bore four slices of cold beetroot and four pickled onions.

The paucity of the food did not dismay Dotty in the least. Used as she was to standing in her kitchen with an apple in her hand at lunchtime, the present spread seemed positively lavish.

Ada helped her guest to one slice of ham, one sausage roll and the sprig of parsley, and invited her to help herself from the remaining bounty. Bertha proffered the salad, and Dotty, chatting brightly, helped herself liberally to mustard and cress and two pieces of tomato. Meaning glances flashed between the three sisters, but Dotty was blissfully unaware of any contretemps.

'No, no beetroot or onion, thank you,' she said, waving away the Meissen dish. There was an audible sigh of relief from Bertha.

The ladies, who only boasted five molars between them, ate daintily with their front teeth like four well-bred rabbits, and exchanged snippets of news, mainly of a scurrilous nature.

'I saw the dear vicar and Mr Shoosmith pass along the street this morning. And where were they bound, I wonder? And what was dear Dimity doing?'

'The washing, I should think,' said Dotty, eminently practical. 'And I can't tell you what the men were up to. Parish work, no doubt.'

'Let's hope so,' said Violet in a tone which belied her words. 'But I

thought

I saw a picnic basket on the back seat, with a

bottle

in it.'

'Of course, it's racing today at Cheltenham,' said Ada pensively.

The conversation drifted to the death of Donald Bailey, and even the Misses Lovelock were hard put to it to find any criticism of that dear man. But Winnie's future, of course, occasioned a great deal of pleasurable conjecture, ranging from her leaving Thrush Green to making a second marriage. 'Given the chance!' added Violet.

The second course consisted of what Bertha termed 'a cold shape', made with cornflour, watered milk and not enough sugar. As it had no vestige of colour or flavour, 'a cold shape' seemed a fairly accurate description. Some cold bottled gooseberries, inadequately topped and tailed, accompanied this inspiring dish, of which Dotty ate heartily.

'Never bother with a pudding myself,' she prattled happily, wiping her mouth on a snowy scrap of ancient linen. 'Enjoy it all the more when I'm given it,' she added.

The Misses Lovelock murmured their gratification, and they moved to the drawing-room where the Cona coffee apparatus was beginning to bubble.

What with one thing and another, it was almost a quarter to four before Dotty became conscious of the time.

She leapt to her feet like a startled hare, grabbing her handbag, spectacle case, scarf and gloves which she had strewn about her en route from one room to another.

'I must get home before dark. The chickens, you know, and Ella will be calling for her milk, and Dulcie gets entangled so easily in her chain.'

The ladies made soothing noises as she babbled on, and inserted her skinny arms into the deplorable jacket which Lulling had known for so many years.

Hasty kisses were planted on papery old cheeks, thanks cascaded from Dotty as she struggled with the front door, and descended the four steps to Lulling's pavement.

The three frail figures, waving and smiling, clustered in their doorway watching the figure of their old friend hurrying towards the car park.

'What sweet old things!' commented a woman passing in her car. 'Like something out of

Cranford.

'

Needless to say, she was a stranger to Lulling.

The overcast sky was beginning to darken as Dotty backed cautiously out of the car park and set the nose of the car towards Thrush Green.

The High Street was busier than usual. Housewives were rushing about doing their last-minute shopping. Mothers were meeting young children from school, and older children, yelling with delight at being let out of the classroom, tore up and down the pavements.

Some of them poured from the school gateway as Dotty chugged along. Several were on bicycles. They swerved in and out, turning perilously to shout ribaldries to their friends similarly mounted.

Dotty, still agitated at the thought of so much to do before nightfall, was only partly conscious of the dangers around her. She kept to her usual thirty miles an hour, and held her course steadily.

Unfortunately, one of the young cyclists did not. Heady with freedom, he tacked along on a bicycle too big for him, weaving an erratic course a few yards ahead of Dotty's car.

The inevitable happened. Dotty's nearside wing caught the boy's back wheel. He crashed to the ground, striking the back of his head on the edge of the kerb whilst Dotty drove inexorably over the bicycle.

She stopped more rapidly than she had ever done in her life, and hurried back to the scene. A small crowd had collected in those few seconds, expressing dismay and exchanging advice on the best way to deal with the injured child.

'You take 'is legs. I'll 'old 'is 'ead!' shouted one.

'You'll bust 'is spine,' warned another. 'Leave 'im be.'

'Anyone sent for the ambulance?'

'Where's the police?'

Amidst the hubbub stood the rock-like figure of a stout American boy, known vaguely to Dotty. His face was impassive. His jaws worked rhythmically upon his chewing gum.

He was the first to address Dotty as she arrived, breathless and appalled.

'He's dead, ma!' he said laconically, and then stood back to allow

P.C.

John Darwin

42469,

stationed unfortunately – for him – at Lulling, to take charge.

8 Dotty Causes Concern

E

LLA

Bembridge was in her kitchen, her arms immersed in the sink.

She was soaking cane. It had occurred to her, during the week, that she had a large bundle of this material in her shed, and with Christmas not far off she had decided to set to and make a few sturdy articles as a change from the usual ties she manufactured for presents.

This sudden decision had been made whilst examining some flimsy containers in the local craft shop in Lulling High Street. Ella picked up waste-paper baskets, roll baskets, gimcrack bottle holders and the like and was more and more appalled at the standard of work as she took her far from silent perambulation about the display.

'Some are made in Hong Kong,' explained the arty lady in charge, in answer to Ella's protestations.

'So what? As far as I can see, the things from there compare very favourably with this other rubbish.'

The arty lady fingered her long necklace and looked pained.

'There's nothing here that would stand up to a week's use,' proclaimed Ella forthrightly. 'Look at this object! What is it, anyway?'