3 Among the Wolves (21 page)

Read 3 Among the Wolves Online

Authors: Helen Thayer

I wondered how prevalent such sharing was. It is generally believed that animals defend their kills from other species and even from each other, and that sharing is not a survival skill in the wild. But we had seen something different.

Throughout North America, wolves and bears share the same territory. Bears have been known to kill pups, but usually only when a bear stumbled onto a den defended by a single wolf. Although bears' sharp claws, powerful shoulders, and massive teeth that can crush a skull are formidable weapons, and evidence of bears killing adult wolves does exist, biologist David Mech has found that the species usually avoid each other.

As we returned to camp, Bill wondered aloud. “Is it possible that some species instinctively understand, at a primitive level, that they're just a single link in the environmental chainâthat to survive, everyone must survive?” We hoped to explore such questions further in the winter, when we would travel farther north to encounter arctic foxes and polar bears as well as wolves.

Close to camp, we startled a group of caribou grazing on spruce boughs. In an instant they raced away, almost without a sound. Because the wolf family's territory was situated in the northern region of the Porcupine caribou herd's wintering grounds, the supply of prey would remain adequate throughout the winter. For thousands of years the herd of about 240,000 has continued a pattern of migration four hundred miles north

across the Porcupine River to the coastal plain of Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Reserve, where their calves are born. In August, with new calves at their side, they migrate back to overwinter in their traditional grounds.

across the Porcupine River to the coastal plain of Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Reserve, where their calves are born. In August, with new calves at their side, they migrate back to overwinter in their traditional grounds.

The annual migration is the basis of sustenance for the Gwich'in people, a native culture of about 7,000 who live along the migratory route. Calling themselves “the people of the caribou,” the Gwich'in have a lifestyle that is traditionally interwoven with that of the Porcupine caribou herd.

My journal writing prompted some interesting interactions with the wolves. One day a loose page from my journal fluttered on the breeze to land ten feet over the wolves' boundary line. The page contained my notes carefully describing a howling session.

Without thinking, I crossed the invisible scent boundary and bent to pick up the page, but looked up just as my hand reached the paper. Alpha had silently approached and stood three feet away. He glanced at the page for a moment and then, with his head cocked to one side, his yellow eyes met mine with a soft but inquiring expression.

I straightened slowly and stepped back. Alpha came forward, took the page in his mouth, and turned toward the rendezvous site. I hoped I could get him to drop the notes. They represented many hours of work, and I wasn't about to give them up without protest. I forced myself to extend my hand. “Alpha, that page is mine,” I said softly.

At the sound of my voice, he stopped and looked back. His steady eyes gave me a look of understanding. Keeping my hand extended, I continued to speak to him in quiet, even tones. With his gaze still fixed on mine, he dropped the paper and then strolled to a shady rock with a barely perceptible fanning of his tail.

I retrieved the page, hoping I appeared more at ease than I felt as I walked back to the tent. Bill returned from washing

a shirt in the stream, having watched the entire episode. We agreed that it was another signal of acceptance. Alpha could easily have kept my precious notes, or even urinated on them in a display of dominance, but he chose to treat me as a friend instead.

a shirt in the stream, having watched the entire episode. We agreed that it was another signal of acceptance. Alpha could easily have kept my precious notes, or even urinated on them in a display of dominance, but he chose to treat me as a friend instead.

During an eight-day spell of unusually mild weather, the mosquito swarms that had survived the early August frost blossomed again. Seeking to escape them, we decided to flee to the windy ridges. Bill and Charlie climbed eastward to explore, while I chose a spot closer to camp to catch up on my journal. I sat on a just-right rock, one with a backrest conveniently carved by nature.

Shortly my attention turned to Denali, who was hurrying up the trail toward me to seek refuge from the mosquitoes. The trail passed within two feet of me. I bent over my notes, pretending not to notice him. He hustled by without so much as a pause or a sideways look, ignoring my existence entirely. He had places to go, and this human he had studied for so long didn't warrant his attention anymore.

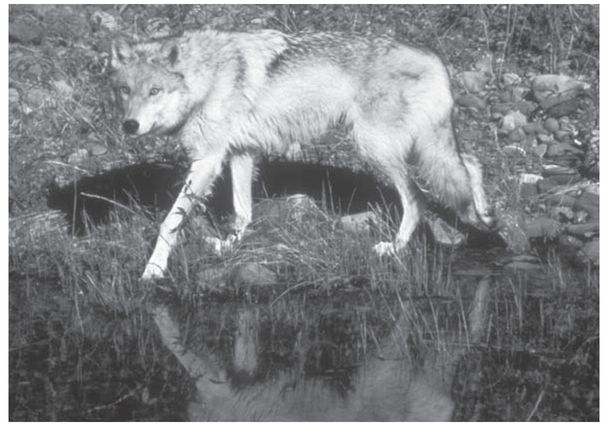

Denali endures mosquitoes by the stream. Breezy ridgetops are the wolves' only escape.

I expected him to continue on to a place of his own choosing. Instead, with his back to me, he sat down directly behind me on the path, twenty feet away. We were two friends sharing the same desire to escape the whining pests. Later Omega passed by, also without visible reaction. Some sign of recognition would have been nice, I thought, but then again, I had been paid a compliment. I was so trusted there was no need to keep an eye on me.

I wrote in my journal, describing this new and surprising event, for another hour. Before returning to camp, I tossed a small rock a few feet along the ridge to see if I could gain the wolves' attention. Denali opened a sleepy eye but, seeing that it was only me, went back to sleep.

That night I read my journal notes to Bill. The last entry read, “Today these wolves taught me the real meaning of unconditional trust. To be so trusted is an experience I shall never forget.”

Parting

A

HARD SEPTEMBER WIND Swept through the mountains from the north to signal the first blast of winter. Heavier frosts blanketed the tundra, and a skim of ice covered the ponds, while the shallow pools were frozen solid. Temperatures dropped into the 20s. Snow showers blanketed Wolf Camp One every few days, covering the mountains in a white mantle. Yellow willow leaves drifted to earth, and fiery red tundra plants disappeared beneath the snow. The shimmering greens, pinks, and blues of the aurora borealis, or northern lights, were visible in the lengthening darkness. An Arctic winter's deep cold had begun its slow spread across the land.

HARD SEPTEMBER WIND Swept through the mountains from the north to signal the first blast of winter. Heavier frosts blanketed the tundra, and a skim of ice covered the ponds, while the shallow pools were frozen solid. Temperatures dropped into the 20s. Snow showers blanketed Wolf Camp One every few days, covering the mountains in a white mantle. Yellow willow leaves drifted to earth, and fiery red tundra plants disappeared beneath the snow. The shimmering greens, pinks, and blues of the aurora borealis, or northern lights, were visible in the lengthening darkness. An Arctic winter's deep cold had begun its slow spread across the land.

Although the pups now traveled longer distances, they still had not joined the pack in a hunt of large animals. They caught lemmings and other rodents close to home and now and then returned with a hare.

One mid-September morning, more than five months after we first arrived at Wolf Camp One, we explored an area three miles away. We crossed ridges dusted with snow and traversed valleys where drifts had accumulated in pockets of willow thickets. Inches-deep surface water lay frozen in the 24-degree air.

After a two-hour trek, we climbed to the top of a ridge and walked along its crest above a deserted beaver swamp. A quarter mile beyond we saw a picturesque lake, rich in aquatic plants, no more than two feet deep and two hundred feet wide, nestled in the tundra at the edge of a taiga forest. Animal tracks in the scant snow cover radiated from the water's edge.

As we approached the lake, a startled lynx scurried to the protection of willows and spruce.

As we approached the lake, a startled lynx scurried to the protection of willows and spruce.

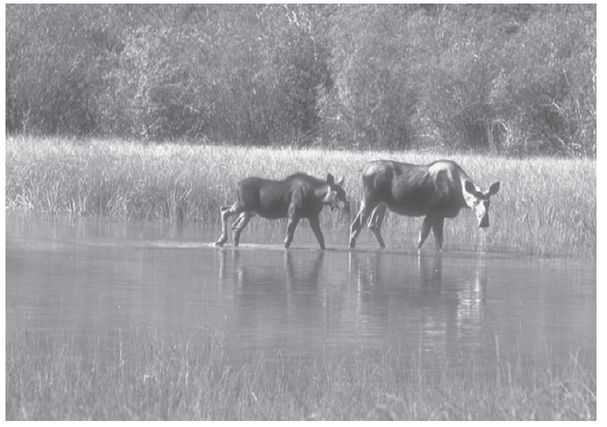

At my approach the mother raises her head with a loud snort, warning me that my unexpected interruption to their foraging is unwelcome.

At the sight of two hares hopping past the far shore, Charlie tried to give chase. We pulled him back. Disgruntled, he barked in protest. The shadowy form of a female moose, barely visible through the branches on the far side of the lake, quickly withdrew into the dense undergrowth.

“A perfect place to live,” I said, soaking up the tranquil scene.

“But a bit far to walk out for groceries,” Bill quipped.

We followed a trail to the far side. At an abrupt turn, we saw a flicker of motion as another lynx silently retreated into the brush.

After a lunch break under a weak sun, we headed back to camp. Storm clouds had built on the horizon. Just as we crossed

the ridge, I remembered a lens cap I had left at our picnic spot. Bill agreed to wait with Charlie while I went back.

the ridge, I remembered a lens cap I had left at our picnic spot. Bill agreed to wait with Charlie while I went back.

At the lake I was surprised to encounter a hulking mother moose and her calf grazing on the near side, pulling up chunks of aquatic plants. At my approach, the mother moose raised her head with a loud snort, warning me that my unexpected interruption to their foraging was unwelcome. Both animals' highly sensitive ears pointed in my direction, tuned to the slightest sound. Their dark eyes watched me intently.

Concerned that the mother might charge in defense of her calf, I waited, motionless. After a long minute of appraisal, mother and calf finally relaxed. The mother bent to pull another mouthful of grass. The calf reached beneath her belly to suckle.

Congratulating myself for stumbling across such an excellent photo opportunity, I slowly reached for my camera and became engrossed in finding just the right angle. After shooting two frames, I bent to change the film. I didn't notice that the female had once more turned toward me. Only when she picked up speed and splashed through the shallows in my direction did I realize the danger.

Terrified, still clutching my camera, I raced back the way I had come, finding speed I didn't know I was capable of. But I was no match for her anger and long legs. As I frantically reached for every bit of acceleration I could muster, she quickly caught up and, with a tremendous, bone-shaking thump, smashed me to the ground with her thick-boned forehead.

Immediately I covered my head, expecting her to strike with her lethal front hooves, but my racing heart and mind met only silence. I dared not move and prayed as never before.

After several minutes that seemed like hours, the moose turned and splashed into the lake. I looked carefully over my shoulder in time to see her rejoin her calf. I shakily rose to my feet as the two evaporated into the surrounding brush and trees.

Now the only sign of the entire incident was a few ripples on the water.

Now the only sign of the entire incident was a few ripples on the water.

Still shaking, but relieved to have suffered only bruises, I returned to Charlie and Bill, who was unsympathetic. “That was a stupid thing to do,” he said succinctly.

He was right. Moose cows with calves are notoriously cantankerous and aggressive. I would never forget this lesson.

We arrived in camp just as a frigid wind picked up and the first snowflakes fell. The fast-moving storm passed in an hour, leaving our site bathed in sunlight. But the light contained little heat and couldn't melt the inch of new snow.

Due to the increased hours of darkness, nighttime observation of hunts was now impossible. Just before daylight in the second week of September, we hiked to our lookout above the junction in hopes of watching the pack leave to hunt. The entire family, except the pups and Beta, trotted our way. They paused to scent-mark the rock and the old snag at the junction, then paralleled our ridge before cutting through a low pass to a valley just beyond.

We quickly trekked along and took a shortcut to a high knoll. Below us, the wolves stopped just as they reached the edge of the scrub trees. Prey was just ahead, judging by their excited milling about and tail wagging. In moments they fanned out. Denali and Omega swept to the left, racing ahead through the cover of the surrounding brush, while Alpha, Yukon, and Klondike stayed back. Suddenly Denali and Omega cut right and chased four Dall sheep out of the undergrowth, back across a clearing, and toward the three crouching wolves, who remained concealed on the edge of thick vegetation beneath spruce trees.

Other books

Take a Chance by Annalisa Nicole

The Burning by Jonas Saul

Queen of the North (Book 3) (Songs of the Scorpion) by James A. West

Emancipating Andie by Glenn, Priscilla

Wheel Wizards by Matt Christopher

Learning to Love Again by Kelli Heneghan, Nathan Squiers

Call to Treason by Tom Clancy, Steve Pieczenik, Jeff Rovin

Sold Out by Melody Carlson

Cedilla by Adam Mars-Jones