29 - The Oath (2 page)

Authors: Michael Jecks

The idea for this book has had a lengthy gestation. It all began when I picked up an Everyman edition of

The Old Yellow Book

, which was the source for Robert Browning’s

The Ring and the Book

. It is not an easy book to read, because it revolves around a series of legal documents, but for a novelist it is sheer gold dust!

Browning’s piece is a poetic reworking of a story he discovered while staying in Florence in 1860. As he tells it, he was wandering round the Piazza of San Lorenzo, past a bookseller in a booth, when the soiled old yellow tome caught his eye. He bought it and took it home, where he devoured it, translating the full story over a number of days.

The book gave the record of an astonishing murder case from 1698 – the assassination of an entire family. The vile behaviour of both groom and father-in-law, set beside the misery of the poor girl-bride and her pathetic lover, were as absorbing as any Shakespearean tragedy, and I could not put it out of my mind, trying to figure out how best to use it in one of my novels.

However, it was only when looking at that other wonderfully dysfunctional family – that of King Edward II and his wife Queen Isabella – that the comparison between the two families struck a chord, and I had to go and look up Browning’s source again. Pretty soon it was clear to me that this was the book I wanted to write. There are changes, however, so anyone familiar with Browning’s work can relax – there is no way they will guess how my story ends!

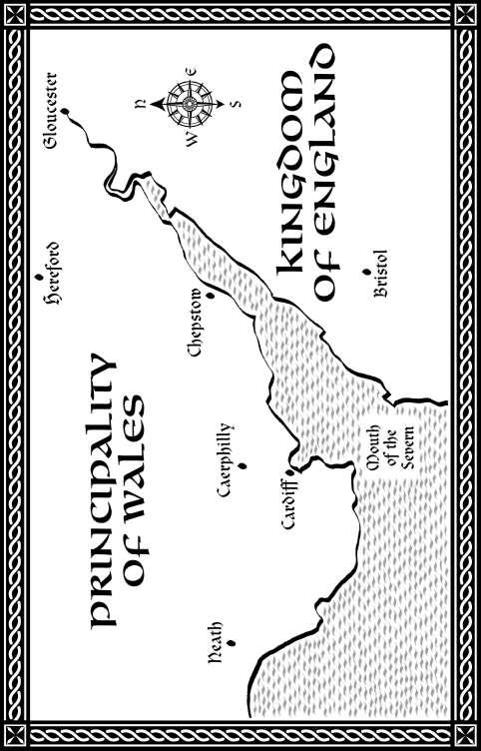

While I have tried, as usual, to be as true to history as I possibly can be, it’s always the small details that give me the biggest headaches. For example, we know that the King set off from London in October 1326 with a small force of men, on the run from Sir Roger Mortimer and the Queen. He may have only had a few men with him, but he had barrels of money, somewhere in the region of £20,000. That was more than the income of England’s king in a year, so he must have had guards. How many? Don’t know.

Likewise, he set off towards Cardiff with even fewer men. He still had his money, but we know that his men were going AWOL and that no one was coming to replace them and fill the ranks. But when he quitted Caerphilly, he left behind a garrison, and still had a force of men about him with whom to travel to Margam and Neath Abbey. How many? Again, I don’t know.

The tale of Despenser’s decline and death is pretty well documented. I am especially grateful to Jules Frusher for the pointer on Edward being, perhaps, at Hereford during Despenser’s execution. No one else has spotted this, but the King’s journey was to Kenilworth Castle, with Lancaster guarding him. Yet Lancaster was present at Hugh Despenser’s hearing and execution. If so, where was the King? It’s perfectly logical to think that Lancaster came with the King and Despenser to Hereford, and at the time, it would have been thought perfectly acceptable to force the King to watch his favourite being executed.

I refer in this book to Edward’s son as the Duke of Aquitaine, which may confuse some readers. Why don’t I call him Prince Edward and be done with it? Well, young Edward had been made Earl of Chester by the King only a short while after his birth, and he was known as such throughout his childhood. Later, at the age of almost thirteen, he was sent to France to pay homage to the French King, in his father’s place, for the English territories in France. For that, he received the gift of Aquitaine, and became a duke. However, he was never actually made Prince of the Realm. To become a prince was not automatic, it was an honour that the King alone could grant. So I use the most senior title that Edward was given.

For that last detail, I am grateful to Ian Mortimer. His

The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer

, and

The Perfect King: The Life of Edward III

, and also his excellent

The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England

have been regularly referred to. I often have to flick through Harold F. Hutchinson’s

Edward II

, as well as Mary Saaler’s book, and that of Roy Martin Haines – all with the same title! Among my more esoteric sources, Terry Brown’s

English Martial Arts

ranks highly, as does

The Medieval Coroner

by R.F. Hunnisett, and

John Leland’s Itinerary

, which is wonderful for those who want to see a landscape through the eyes of someone who was alive 500 years ago. I am also hugely indebted to Jules Frusher for her website ‘Lady Despenser’s Scribery’ at http://despenser.blogspot.com. Jules has given me enormous help.

Which is why I have to quickly add that no matter how good all these, and other individuals are, the errors are sadly still all my own.

But errors and omissions aside, I hope that this tale, which is still thrilling to me, nearly 700 years after the events I describe, will take you back in time to a period when life was undoubtedly nastier, colder, wetter, more painful and more dangerous. And in so many ways, still extremely attractive.

Michael Jecks

North Dartmoor

November 2009

Bristol

Her nightmare always began in the same way.

It started with the urgent cry.

‘Cecily? Cecily, help me!’

Cecily hurried to her mistress’s door as soon as she heard the summons. A maid of almost thirty, short and mousy-haired under her wimple, she had an oval-shaped face and smiling green eyes. She walked in to find Petronilla Capon sitting on her bed’s edge, waving a hand in the direction of the cot, from which all the screaming emanated.

‘Good Cecily, can

you

do anything with him?’

Her mistress was almost eighteen years old. Quite tall, she had the sort of figure that men eyed with unconcealed lust, their wives with simple jealousy. Her face was unmarked with fear or sadness, which was a miracle after the last four years, but now there was an expression of mild panic on it which did not so much mar her beauty as add to it.

‘Let me, mistress,’ Cecily said comfortably, crossing the floor.

Cecily had been her maid for years now and was as much a part of Petronilla’s life as the cross which hung from the silver chain about her neck. Everyone who knew Petronilla knew how devoted Cecily was to her and, since the birth of Little Harry, the maid had grown still more attentive.

Little Harry looked up at Cecily with his blue-black eyes still fogged with despair. ‘Hush, little one,’ Cecily said, beginning to wipe away the worst of the vomit with his slavering clout

1

.

‘I did what you said,’ Petronilla stated with weary conviction. ‘He had finished feeding, and I just had him over my shoulder . . .’

‘You should have stopped feeding him a little earlier, mistress. Then, perhaps, you could have burped him

before

he was sick.’

Petronilla gave her a wretched smile. ‘I don’t understand the boy. He cries all night, sleeps all day, and when he whimpers and I try to feed him, he does this to me. Ungrateful little monster, aren’t you? Oh no, what now? Why is he crying

now

, Cecily?’

In answer, her maid picked him up and sniffed at his backside before pulling a face. ‘Why do you think?’

Her mistress often behaved as though she was a child herself still, thought Cecily. When she had married and moved to her husband’s house near Hanham, despite the fact that it was only some three miles outside Bristol, the girl had reacted as if it were the edge of the world. Cecily had looked after Petronilla from her eighth year, and when the girl had married Squire William de Bar nearly four years ago, Cecily had gone to Hanham with her. When Petronilla’s husband had evicted Cecily, forcing her from his young bride’s side, the maid had been distraught.

It had been an awful time. When Cecily was dismissed and sent back to Bristol, Arthur Capon was reluctant to give her house room, seeing her as a waste of space.

Cecily carefully unwrapped the boy, taking off the swaddling-bands then cleaning him with the old tail-clout

2

. The soiled bands were dropped into the bucket ready for soaking and washing, and then she massaged his limbs tenderly with a little oil of myrtle. It was hideously expensive, but there was nothing too costly for the young master. She wrapped him in fresh swaddling bands, then, cooing and shushing, she cuddled him close.

Petronilla watched her with a wan smile. The birth had been easy enough, but like so many new mothers, she was exhausted after too little sleep in the last two weeks.

‘Mistress, sit and rest. I can look after the little master for you. He just wants company, I’ll be bound.’

‘All

I

want is my sleep,’ Petronilla said with some acid. ‘Harry keeps me awake all night.’

Cecily said nothing. There was no need – both knew that it was Cecily who most often went to the baby in the watches of the night.

Taking the little mite with her as she left her mistress, Cecily quietly closed the door. Petronilla was already on her bed, her eyes closed, and young master Harry snuffled and nuzzled against Cecily’s breast. He seemed happy to accept her as a surrogate mother.

She murmured to him as she walked through the passageway to the hall. Little Harry looked up at her with those wide, trusting eyes, and she smiled as he burped.

Cecily had sworn to serve his mother and protect Harry, and she would not break that vow.

*

That part of her dream was always so happy. She had been content, then, easy in her mind. Before that, while Petronilla was away in Hanham, her life had been empty, her existence anxious, because unnecessary servants were easily discarded. Now, with Petronilla back once more, it seemed that Cecily could count on a secure future.

Later that same morning, Cecily respectfully ducked her head to Petronilla’s parents as she passed through the hall on her way towards the screens.

Arthur Capon sat near the fire, ignoring Cecily as he spoke with his wife who was sitting in the light near the window’s bars and working on a fine cap for her grandson, peering closely with her poor eyesight.

Cecily went to the little pantry near the front door. Here she could dandle the boy on her knee while chatting to the bottler. It was always best to keep a child busy. Just as he needed his arms and legs restrained so that they might grow firm and straight, there were other risks: a child might stare too long at a single bright light, and that would produce a squint in later years. Or a babe set to sleep in a hanging cot might wriggle free of the bindings, and fall and hang himself. There were so many dangers. But at least people tried to protect children. No one would hurt a child on purpose, would they? That would be wicked.

So she had believed, in her innocence.

In her dream, she remembered the knocking at the door, reminding her of her failure, her dishonour.

She had sworn to protect Harry. And instead . . .

The rapping was insistent. Cecily had remained sitting while the bottler rose from his stool and walked to the screens. There was nothing unusual in visitors coming to the house, for Arthur Capon was a successful merchant, and also a money-lender. Men often called by to speak with him, and so, as the bottler opened the door, Cecily did not look up. It was just a normal morning.

Except then it ceased to be normal.

There was a shout: full of malice, it was enough to startle Cecily and make her look up. The door was suddenly thrust wide, and the bottler remonstrated, only to make a strange noise, a watery, gurgling sound like Little Harry, and then he stepped back, falling hard on his rump. Seeing him, Cecily almost laughed aloud. He was so proud of himself and his position in the world, that to stumble like that would mortify him. But the smile was struck from her face as she saw the blood.

And then the men entered.

She told the jury at the inquest, held that same afternoon, that first inside was the squire, Petronilla’s husband.

Squire William de Bar was like a man made of steel that day, she said. His blue eyes were cold and uncaring, and as he strode over the threshold, his sword was already dripping with the bottler’s gore. He kicked the body aside before marching into the hall towards Arthur Capon and, as the older man demanded to know what he was doing in the house unannounced, he thrust his sword into his father-in-law’s breast. Capon stared at the man disbelievingly, his mouth working, but no words came. He tried to stand, but that merely forced his body further onto the blade, and the blood gushed from his nostrils and mouth as he attempted to cry for help.