(20/20)A Peaceful Retirement (12 page)

Read (20/20)A Peaceful Retirement Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #England, #Country life, #Pastoral Fiction, #Country Life - England

Meanwhile I started to work on the church pamphlet. Basically, I decided, it provided useful facts about the building, but needed a few additions. For instance, a rather attractive stained-glass window in memory of twin sons killed in the First World War had no mention at all, which seemed a pity. The family was an ancient and honourable one whose seat had been at Beech Green for centuries. The last of the family had left in the fifties, and it was now a nursing home. (Perhaps it was this one Mr Lamb had in mind for me?)

There was also a fine Elizabethan tomb in the Lady Chapel, with rows of little kneeling children mourning their recumbent parents. This had been dismissed in the present leaflet with: 'The Motcombe tomb is to be found in the Lady Chapel.' I decided to give it more prominence in my version.

To this end I spent a happy morning in Caxley Library looking up the history of both families, and was surprised at how quickly the time passed whilst engaged on my simple researches.

Driving home I began to wonder if this sort of gentle activity was what I needed to fill my days in the future. I began to wax quite enthusiastic and wondered if a small book about local history would prove a worthwhile project. It could have maps in it, I thought delightedly. I like maps, and I imagined myself poring over old maps and new ones, and deciding how large an area I would cover, and what scale I should choose for reproducing them.

Caxley itself could provide a wealth of material for a volume of local history, but I decided that other people had done this before me, and in any case I had no intention of burdening myself with trips to the crowded streets of our market town to check facts and figures.

No, I shall concentrate on something simpler, Beech Green, say, or Fairacre. I remembered some of dear Miss Clare's memories of her thatcher father and his work, and of the way of life she had known as a child in the house which was now mine. If only I had written them down at the time!

Such pleasurable musings accompanied me as I went about my daily affairs. When at last I settled down one wet afternoon to write up my notes about the two families commemorated in my parish church, I began to have second thoughts.

This writing business was no joke. Both accounts were much too long. I did some serious cutting and editing, then began to wonder if my predecessor had discovered the same difficulty in describing the earlier tomb, which accounted for his terse advice to visit the Lady Chapel.

I put down my pen and went to make a pot of tea. I needed refreshment. Perhaps it would be better to devote my energies to recording people's memories, as I had first thought, and writing my own diary next year. I was beginning to realize that historical research and, worse still, writing up the results was uncommonly exhausting.

I had a chance to broach the subject of recording memories when Bob Willet arrived with Joe Coggs the next Saturday.

'We've come to split you up,' announced Bob.

I was not as alarmed as one might imagine. Translated it meant that he and Joe were about to divide some hefty clumps of perennials which had been worrying Bob for some time.

They went down the garden bearing forks and chatting cheerfully, while I went indoors to make some telephone calls.

I could hear them at their task. Bob was busy instructing his young assistant on the correct way to divide plants.

'You puts 'em back to back, boy. Back to back. Them forks. Pretty deep. Put your foot on 'em, so's they gets well down. That's it. Now give 'em a heave like.'

I could hear the clinking of metal as the operation got under way, then a yell.

'Well, get your ruddy foot out o' the way, boy! You wants to watch out with tools.'

I hoped I should not be called upon to rush someone to hospital, and was relieved to hear no more yells, just Bob's homely burr as he continued his lesson.

Some time later, their labours over, we all sat down at the kitchen table with mugs of tea before us, and a fruit cake bought from the WI stall in the middle.

My two visitors did justice to it and Bob congratulated me.

'You always was a good hand at cake-making. My Alice said so.'

This was high praise indeed as Mrs Willet is a renowned cook. However, common honesty made me confess that I had not made this particular specimen.

I broached the subject of Bob's early memories, and drew some response.

'Well now, I don't really hold with raking up old times, but there's a lot I could tell you about Maud Pringle in her young days as'd make you sit up.'

The dangers of libel suddenly flashed before me. Perhaps old memories were not going to be as fragrant and rosy as I imagined.

'I wasn't thinking of

people

so much,' I began carefully, 'as different ways of farming, perhaps, or household methods which have changed.'

Bob looked happier.

'You can't do better than to talk to Alice. She remembers clear-starching and goffering irons and all that sort of laundry lark. She sometimes did a bit for old Miss Parr. She had white cambric knickers with hand-made crochet round the legs. They took a bit of laundering, I gather.'

I said I should love to hear Alice's reminiscences, and meant it.

'I could put you wise to old poaching methods,' said Bob meditatively. 'Josh Pringle, over at Springbourne, he was the real top-notcher at poaching. He'd be a help too, but I think he's in quod at the moment. He's as bad as our ...'

Here he broke off, having recalled that young Joe was the son of the malefactor he had been about to mention.

'As I was saying,' he amended with a cough, 'Josh is as bad as the rest of them, but he'd remember a lot about poaching times, and dodging the police.'

I began to wonder if I had better abandon my plans for enlightening future generations. Danger seemed to loom everywhere.

'Then there was that chap that worked for Mr Roberts' old dad,' went on Bob, now warming to the subject. 'Can't recall his name, but Alice'd know.'

'What about him?'

'He hung himself in the big barn.'

This did not seem to me to be a very fruitful subject for my project. Dramatic, no doubt, but too abrupt an ending.

"What about the clothes you wore as a child? Or the games you played?' I said, trying to steer the conversation in the right direction.

'Ah! You'd have to ask my Alice about that,' said Bob rising.

I said I would.

When they had departed, Bob with a message to Alice to ask if I might call to have a word with her about my literary hopes and Joe with the remains of the WI cake, I decided to ring John Jenkins.

I told him about my conversation with Bob Willet and my plan to visit Alice. Would it be convenient to borrow the tape recorder after I had seen her?

'Have it now,' urged John. 'I never use the thing, and if you've got it handy you may get on with the job.'

It sounded as though he doubted my ability to go ahead with the project.

'I'll bring it over straight away,' he said briskly, 'and show you how it works.'

He was with me in twenty minutes. I was relieved to see that the equipment was reassuringly simple, just a small oblong box which, I hoped, even I could manage.

'I think this plan of yours is ideal,' he said when he saw that I had mastered the intricacies of switching on and off. 'It's the sort of thing you can do in your own time, and there must be masses of material.'

'If it's suitable,' I commented, and told him about Bob Willet's memories of Mrs Pringle's youthful escapades and Josh Pringle's brushes with the law. He was much amused.

'Yes, I can see that a certain amount of editing will be necessary.'

He was silent for a moment and then added: 'You could tackle another local subject, I suppose. I mean some historical event like the Civil War. There were a couple of splendid battles around Caxley, and one of the Beech Green families played a distinguished part.'

This I knew from the church pamphlet I was altering, but I expressed my doubts about my ability to do justice to such a theme.

'I never know,' I mused, 'which side I should have supported.'

'As Sellar and Yeatman said in

1066 and All That

, the Royalists were Wrong but Wromantic, and the Cromwellians were Right but Repulsive.'

'Exactly. On the whole I think I'd have been a Royalist. Their hats were prettier.'

'So it's no-go with a historical dissertation?'

'Definitely not. I'll try my more modest efforts.'

I looked at the clock.

'Heavens! It's half past seven. You must be hungry.'

I mentally reviewed the state of my larder. A well-run pantry should surely have a joint of cold gammon ready for such emergencies. Mine did not.

'I could give you scrambled eggs,' I ventured.

'My favourite dish,'John said gallantly. "You do the eggs and I'll do the toast.'

And so we ended the evening at the kitchen table, and were very merry.

The next time I saw Bob Willet he brought a message from his wife.

'Alice says could you put off this interview lark until after Christmas? What with the shopping and all the parties she's helping at, she can't see her way clear to think about old times.'

I said I quite understood and I would try my luck in the New Year.

In a way I was relieved. I too had a good many things to do before Christmas, and it would give me time to collect my thoughts about the proposed work.

'You're putting it off,' said Amy accusingly, when I told her.

'I know that, but the world seems to have managed without my literary efforts so far, and I reckon another few months won't make much difference.'

Meanwhile, much relieved, I finished my Christmas cards, decorated a Christmas tree for the window-sill, and looked forward to the party at Fairacre school.

Fog descended overnight, and the last day of term when the party was to take place, was so shrouded in impenetrable veils of mist that it seemed unlikely to clear.

Everything was uncannily still. Not a breath of wind stirred the branches or rustled the dead leaves which still spangled the flower beds.

There were no birds to be seen, and no sound of animal life anywhere.

There was something eerie about this grey silent world. One could easily imagine the fears that plagued travellers abroad in such weather. It was not only the fear of evil-doers, the robbers, the men who snatched bodies from graves, the boys who picked pockets, but the feeling of something mysterious and all-pervading which made a man quake.

By midday, however, the fog had lifted slightly. It was possible to see my garden gate and the trees dimly across the road. No sun penetrated the gloom, but at least the drive to Fairacre would not be hazardous.

I wore my new suit and set off happily. This would be my first Christmas party as a visitor, and I looked forward to seeing all my Fairacre friends.

I was not disappointed. There were the Willets, the Lambs, Mrs Pringle with her husband Fred in tow, and of course the vicar and Mrs Partridge and a host of others.

Jane Summers, resplendent in a scarlet two-piece, and Mrs Richards in an elegant navy blue frock greeted us warmly, and I had a chance to admire the look of my old quarters in their festive adornment.

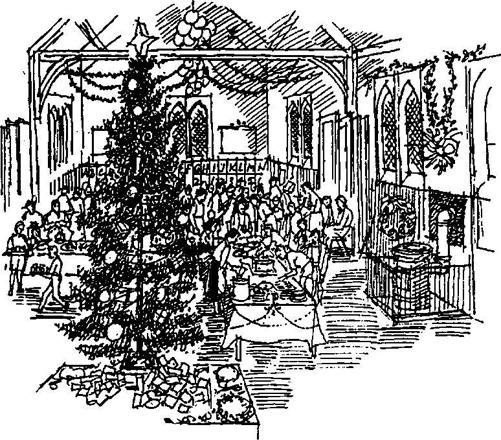

I was glad to see that the infants' end of the building still had paper chains stretched across it. The partition between the two classrooms had been pushed back to throw the two into one, and Miss Summers' end was decorated in a much more artistic way than ever it was in my time.

Here were no paper chains, but lovely garlands of fresh evergreen, cypress, ivy and holly. The splendid Christmas tree was glittering with hand-made decorations in silver and gold, and the traditional pile of presents wrapped in pink for girls, and blue for boys lay at its base.

I was pleased too to see that Mrs Willet had made yet another of her mammoth Christmas cakes, exquisitely iced and decorated with candles.

The vicar gave his usual kindly speech of welcome, and we were all very polite at first, but gradually the noise grew as tea was enjoyed. We were waited on, as usual, by the children and it was good to see how happy and healthy they looked.

The hubbub grew as we all moved about after tea, greeting friends and catching up with all the news.