20 Master Plots (9 page)

Authors: Ronald B Tobias

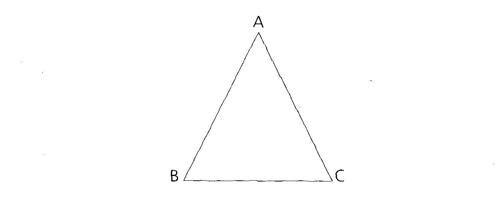

Add a third major character, Chuck (C). Beatrice loves Chuck, not Alfred. The character dynamic in this case is not three, but

six,

because there are six possible emotional interactions:

• A's relationship to B;

• B's relationship to A;

• A's relationship to C;

• B's relationship to C;

• C's relationship to A;

• C's relationship to B.

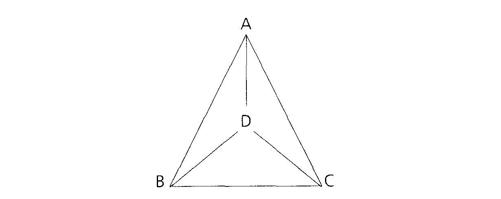

Now add a fourth major character, Dana (D). Chuck loves Dana, not Beatrice or Alfred. The character dynamic is now

twelve,

with twelve emotional interactions possible:

• A's relationship to B, and B's to A;

• A's relationship to C, and C's to A;

• A's relationship to D, and D's to A;

• B's relationship to C, and C's to B;

• B's relationship to D, and D's to B;

• C's relationship to D, and D's to C.

As a writer, you certainly aren't obliged to cover

every

angle of all the possible relationships. But you'll find that the more characters you add to the mixture, the more difficult it will become to keep up with all of them and to keep them in the action. If you include too many characters, you may "lose" them from time to time—in effect, forget about them—and when you try to bring them back into the action it will seem forced and artificial. Pick the number of characters that you feel comfortable with. That number should allow maximum interaction between characters to keep the reader interested, but not so many that you feel like you're in the middle of an endless juggling act.

Don't even think of adding a fifth major character. If you did, the character dynamic would be

twenty.

(Sounds like a nineteenth-century Russian novel, doesn't it?)

Obviously it would be hard if not impossible to keep up with the emotional relationships and interactions with a dynamic of

twenty. Think of the incredible burden on the writer trying to juggle twenty character interactions simultaneously. Juggling twelve is possible, but it takes great skill: You'd have major characters going in and out of phase constantly, with usually no more than three majors in a scene at any one time, except for big confrontation scenes and the climax.

Now let's go to the other extreme and look at the original scenario of two major characters with a dynamic of two. We're confined to seeing how Alfred acts in the presence of Beatrice and how Beatrice acts in the presence of Alfred. The situation doesn't offer us the flexibility we need to be comfortable developing their characters. Of course it's been done, and done well, particularly on the stage. But having just two major characters limits what you can do with those characters, and you'll need to be a strong, inventive writer to overcome the handicap.

This brings us to the Rule of Three. If you pay attention to the structure—whether it's the classic fable or fairy tale or folktale, or a B-movie on television—you'll notice that the number three holds strong sway. Character

triangles

make the strongest character combination and are the most common in stories. Events also tend to happen in threes. The hero tries three times to overcome an obstacle. He fails the first two times and succeeds the third.

This isn't a secret numerology thing. There's actually a rather obvious reason for it: balance. If the hero tries to do something the first time and actually does it, there's no tension. If the hero tries to do it twice and succeeds the second time, there is some tension, but not enough to build on. The third time is the charm. Four times and it gets boring.

The same is true with characters. One person isn't enough to get full interaction. Two is possible, but it doesn't have a wild card to make things interesting. Three is just right. Things can be unpredictable but not too complicated. As a writer, think about the virtues of the number three. Not too simple, not too complicated—just right.

Which brings us to the classic triangle: three major characters with a dynamic of six. Now you'll have room to move. The romantic comedy

Ghost,

with Patrick Swayze, Whoopi Goldberg and Demi Moore, gives us a clear model. In the story Swayze and

Moore's characters are in love; he's killed during a mugging. He becomes a ghost but can't communicate with her.

Enter Goldberg, a fake psychic, who learns (to her surprise more than anyone's) that she really

can

communicate with the dead (Swayze). This is more than she can take, and she wants no part of it. But Swayze convinces her she must talk to Moore because she's in danger (from the man who had him killed).

If the story had been set up that Swayze's character could talk directly to Moore's from the beyond, the story wouldn't have any real tension to it. But since he must talk through a third and thoroughly unlikely person (we find out she's got a record for being a con artist), the plot suddenly takes on greater depth and comic possibilities:

1. Swayze must convince Goldberg that he's a ghost and is talking to her from the great beyond, then

2. Goldberg must convince Moore that she really can talk to her dead boyfriend.

All six character interactions take place in the story:

• Moore relates directly to Goldberg and indirectly (through Whoopi) to her dead boyfriend;

• Swayze relates directly to Goldberg and indirectly (again through Whoopi) to his living girlfriend;

• And Goldberg (as the medium) relates directly to both Swayze and Moore.

The character triangle looks like this:

It's a tight package with a twist that works well.

Or take another ghost story, the Gothic romance

Rebecca

by Daphne du Maurier (later made into a film by Alfred Hitchcock).

The setup is simple: Dark, brooding and mysterious Maxim de Winter brings back a naive, head-over-heels-in-love bride to his estate, where the memory of his dead wife Rebecca still looms very large, especially through the character of the housekeeper, a sinister woman who was (and still is) entirely dedicated to the dead woman. De Winter is haunted by his beautiful, dead wife and cannot return the love his new wife lavishes on him.

In

Rebecca,

the ghost of the dead wife doesn't literally stalk the halls of the mansion, but she does figuratively. Reminders of her are everywhere. The new wife (who curiously never has a name in the film) cannot overcome the presence of the old wife. To make matters worse, the housekeeper plots the new wife's destruction.

All three points of the triangle are developed:

• Maxim de Winter's relationships to the housekeeper and his new wife (both of which are affected by Rebecca);

• The housekeeper's relationships to de Winter and his new wife (again both affected by Rebecca); and

• The new wife's relationships with her husband and the housekeeper (you guessed it, all affected by Rebecca).

Rebecca, whom we never see in flashback or ghostly vision, affects everyone and everything in this story. So the triangle looks different because all three major characters are affected by a fourth character

who never appears.

The triangle then, would look like this:

In terms of sophistication of plot,

Rebecca

is the better story.

Ghost

is simple and straightforward and clever, but it lacks depth of character. We enjoy it mainly because of its cleverness, which is manifested through humor.

Rebecca,

on the other hand, even with its Gothic coloring (cliffs and storms and huge, hollow castles) deals more with people.

So when you develop your opposing forces in your deep structure, decide which level of character dynamic you want in your book. Ask yourself how many major characters best suits your story: two? three? four? And understand the consequences of having two, three or four major characters.

THE DYNAMIC DUO

Plot and character. They work together and are inseparable. As you develop your story, remember that the reader wants to understand why your major characters do what they do. That is their motivation. To understand why a character makes one particular choice as opposed to another, there must be a logical connection (action/reaction). And yet you shouldn't have the character behave predictably, because then your story will be predictable (a nice way of saying

boring).

At times the character's behavior should surprise us ("Why did she do

that?"),

but then, upon examining the action, we should understand why it happened. Just because there's a logical connection between cause and effect doesn't mean it has to be obvious.

Aristotle felt that characters became happy or miserable as a result of their actions. The process of becoming happy or miserable is plot itself. The events that happen to the protagonist change her. That change will probably leave her happier or sadder (and perhaps wiser). Aristotle put plot before character. Today we don't agree that must be the case. But it is true that we understand

who

a person is by what he

does.

Action equals character. What a character says about himself isn't that important. Paddy Chayefsky, the author of such films as

Network

and

Hospital,

said that the writer is first obligated to create a set of incidents. Once you've established those incidents (plot beats), you should create

characters who can make those incidents happen. "The characters take shape in order to make the story true," said Chayefsky.

Your character will come to life by doing, not by sitting around and telling us what she feels about life or about the crisis of the moment.

Do,

don't just

say.

Then your major characters will develop in relation to the other characters in your story.

There's a short scene in

Lawrence of Arabia

that gives insight into the main character. The point of the scene is to show that Lawrence is determined to achieve his goal, whatever the personal cost. He harbors an almost pathological fear that he's too weak to accomplish his goal of uniting a fractured Arabia. He's not your typical macho type out to conquer the world; in fact, Lawrence is afraid of any kind of pain. It would be easy for him to sit around with some of his buddies and say, "Gee, fellas, I'm not sure I'm really up to this task." Talk is cheap.

The scene in the film is far more intense and doesn't have a single word of dialogue. Pure action. Alone, Lawrence lights a match and holds it between his fingers until the flame burns him. In the context of the story this isn't bravado. We know Lawrence is afraid of pain, so we understand when he tries to overcome that fear by letting the match burn his fingers. This scene becomes important later in the film, when Lawrence is captured and tortured by the Turks.

Plot, then, is a function of character, and character is a function of plot. The two can't be divided in any meaningful way. Action is their common ground. Without action there is no character, and without action there is no plot.