2 Death Makes the Cut

Read 2 Death Makes the Cut Online

Authors: Janice Hamrick

To my parents James and Joyrene Pope and to my daughters Jennifer and Jacqueline Hamrick with all my love

Acknowledgments

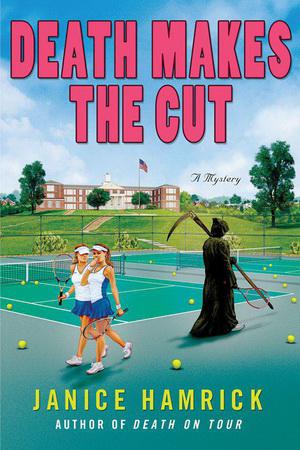

I am deeply indebted to the many people who made this book possible. My heartfelt thanks go to my editor, Matt Martz, not only for his precision editing, but also for his guidance, encouragement, and enthusiasm, to my agent, David Hale Smith, for his ongoing support and advice, to Anna Chang for her amazing copyediting skills, and to artist Ben Perini and designer David Baldeosingh Rotstein for another brilliant cover that made me laugh out loud. I am more grateful than I can express to author Stefanie Pintoff for her generous and much-needed words of wisdom. I would like to thank the many others who have made my first year in the business so much fun: Sarah Ann Robertson, Scott Montgomery, John Kwiatkowski, Anne Kimbol, Barbara Peters, Frank Campbell, Hopeton Hay, and Kaye George. I am also grateful to my friends at Get Up ’n Go Toastmasters who taught me to breathe and who make me look forward to Monday mornings. And finally, my thanks go to Cindy Marszal for reading my first drafts and introducing me to the ’burgh (FTC).

Contents

Chapter 1

FIGHTS AND FINES

The shouting started just after lunch, angry and loud enough to make me spring down from the chair that I’d been standing on to hang posters and race for the door of my classroom. I burst into the hallway, then stopped confused. Farther down the corridor, a couple of teachers peered out of their rooms like meerkats on alert, ready to scatter at the first hint of danger. Otherwise, the hall was empty.

A furious male voice boomed through the air, echoing along gray concrete floors and walls, coming from everywhere and nowhere. In the open building, sounds carried from the first floor to the second and from one corridor to the next without hindrance. When two thousand kids were on the move, the sound of feet on stairs, the talking, giggling, shouting, and the clang of lockers became an indescribable din. On this day, the last day of summer vacation, the school was all but deserted, and, until a moment ago, the halls had been silent.

White-knuckled, I grasped the railing of the stairwell and leaned out ever so slightly, trying to see movement on the first floor far below without really looking. I loathed heights. Even behind a firm rail, the drop made me feel a little queasy. A second shout made me turn. This time I had it. The argument was coming from the classroom directly across the hall. Fred Argus’s room. Dashing around the intervening stairwell, I threw open the door with a bang.

Two men turned startled faces in my direction. Fred Argus, my fellow history teacher, stood behind his desk as though poised to flee, open hands raised to his adversary as though in supplication. The other guy was a stranger, a big man with the thick neck of a fighter, black-eyed and red-faced. He turned a malevolent gaze on me, and I felt an unexpected stab of fear. An aura of rage, barely contained and menacing, flowed from him. Alarmed, I stood a little straighter.

“What’s going on, Fred?” I asked, trying to keep my tone light but not taking my eyes off the newcomer.

“Nothing that concerns you,” the stranger answered for him. His was the voice that had been doing the shouting, a deep bullhorn of a voice, the kind that could carry across a crowded room or shout down a mob.

I ignored him. “Fred?”

Fred gave me a look of mingled fear and hope, like a beaten dog receiving a pat from his master. He didn’t quite come out from behind the shelter of his desk, but he did straighten a little from his crouching position.

“Mr. Richards has concerns about the tennis team,” he said, shooting a nervous look at the stranger.

“The tennis team?” I repeated blankly.

Of course I knew that Fred was the tennis coach, something I’d always found a little ironic, considering he was on the wrong side of sixty and smoked at least two packs of cigarettes a day. The sight of the white toothpicks that he called legs flashing from beneath a pair of spandex shorts had been known to cause convulsions in even the strongest of women. I also knew that our tennis team, although possibly the worst in the league, was one of the few high school teams which every kid, regardless of experience, was welcome to join. What I didn’t know was why anyone would need to raise his eyebrows, much less his voice, for anything remotely related to the Bonham Breakpoints.

Mr. Richards took a step toward me, and again I felt a small flash of fear, so out of place in a bright classroom on an August afternoon. I knew from Fred’s return to full flight-or-fight stance that he felt it too—this man was very close to violence.

“Is your child thinking of joining the team, Mr. Richards?” I asked quickly, trying to keep him talking so that he would focus on something, anything other than his anger. He reminded me of a bull at a rodeo. He’d thrown his cowboy and was now waiting for the clown to get a little closer.

His eyes narrowed, and he shot a glance at Fred that could have stripped paint from a wall.

“My son IS the team. The only real player you’ve got. And this old son of a…”

I cut him off. “Did you know Coach Fred started the tennis program here at Bonham, Mr. Richards?”

This distracted him for an instant. He looked at me like I was crazy. I went on in the most cheerful voice I could manage.

“Yes indeed, Coach Fred is the reason we have a tennis team at all. He was the one who lobbied to get the courts built. And he did all the paperwork and lobbying to get us into the league. We wouldn’t have tennis at this school if it weren’t for him.”

I could have gone on like this forever. I was watching Mr. Richards’s face, hoping to see the redness vanish or at least fade, but he drew in a deep breath in preparation for another tirade. Where in the world were those other teachers?

“Get out!” he shouted in a voice that practically blew my hair back from my face. He took another step toward me, and I felt a chill run down my spine.

“No.” I stood my ground, holding his gaze with one of my own. My best teacher look, in fact, complete with the all-powerful lifted eyebrow. It was a look that could quell thirty teenage boys, and now it made this arrogant bully pause. I seized the moment.

“It’s time for you to leave, Mr. Richards. If you have anything further you’d like to discuss about the tennis team or any other subject, I’d suggest you make an appointment with Mr. Gonzales, our principal, who will be happy to address your concerns.”

For a moment none of us moved. In the silence a clock somewhere in the room ticked out the seconds. Mr. Richards hesitated another instant, then erupted with a bellow, kicking a desk out of his path. It toppled over with a crash. I jumped but held my ground.

Glaring at me, he halted inches from my face, at the last instant deciding not to strike me. He tried to stare me down. I stared back, partly in defiance, mostly just frozen with shock. Either way, it finally worked. He backed down.

“I’ll do that. This isn’t the end of this conversation,” he said to Fred. “You fucking bitch,” he added to me as he stomped by.

“Mr. Richards,” I said, my voice quiet.

He half turned.

“Don’t come back. If I see you in this hall again, I’ll call the police first and ask questions later.”

He didn’t bother to reply. Cautiously, I followed him out the door, watching to make sure he actually went down the steps and out the double doors to the quadrangle. He did. I heard the crash the double doors made as he slammed through them, sending them banging in unison against their doorstops. He was halfway across the courtyard before the springs drew the doors shut again with a muffled clang. Silence returned to the hall. Not one teacher bothered to look out again, the cowards. I drew a deep, shaky breath, then returned to the classroom.

Fred had collapsed into the chair behind his desk, looking curiously shrunken and defeated. He stroked the smooth wood of his little desk clock with fingers that trembled as though with cold. The clock had been a parting gift from his coworkers when he’d left his original career to become a teacher some twenty years earlier. I wondered if he was feeling sorry he’d made the job switch. Noticing my glance, he set the clock back in its usual place on the corner of his desk, then let his hands drop into his lap.

“You know, I thought he was going to hit me,” he said in a wondering tone.

I pulled up a chair and sank into it, taking the clock into my own hands, admiring it. It was a pretty little thing made of polished mahogany, about the size of my two fists held together, standing upright like a miniature grandfather clock. Along the bottom was a small drawer complete with lock and tiny key, and on the back an engraved plaque.

Now that the argument was over, I could feel a reaction of my own setting in. My fingers trembled enough that I decided to put the clock down.

“So what did he want anyway?” I asked.

Fred answered slowly, as though puzzled. “I’m not even sure. Something about wanting his boy, Eric, to be team captain. Which is ridiculous because I don’t have anything to do with that. The kids vote for team captain. I don’t think Eric even signed up to be in the running.”

“What does the team captain do?” I asked.

I didn’t care, but I didn’t want to leave him just yet. I didn’t like the gray hue of his face or the way he slumped in his chair—it made me wonder about the condition of his heart for the first time. For years he had been the head of our team of history teachers, a vibrant, passionate man, completely dedicated to his students and to the school. He and I argued occasionally over things like lesson plans, but I usually deferred to him in the end. I liked to tell him it was because I figured he’d been an eyewitness to most of the things we taught. But until now, I’d never thought of him as being old.

He didn’t answer for a long moment. Then finally he looked up as though confused. “I’m sorry. What did you ask?”

I repeated the question.

“Ah, that. It’s nothing much. The captain is responsible for little things like maintaining the calling chain and acting as my assistant for the away games. It’s mostly just an indication of the other players’ respect. I suppose it might look good on a résumé,” he added as an afterthought.

I frowned. “Then I don’t see what he wanted. If he tries to bully you again, Fred, you need to call someone. Preferably the police.”

“Oh, I don’t think that will be necessary,” he said, not quite meeting my eyes. “A one-time occurrence, tempers getting a bit out of hand. Nothing to worry about.”

“Nothing to worry about? Fred, that guy was two seconds from hauling off and hitting you. What exactly is going on?”

“Nothing. No, it’s nothing.” He rose abruptly, glancing one last time around his classroom, taking in the rows of desks, the whiteboards, the newly hung maps and posters on the walls. Everything appeared neat, clean, and ready for the first day of class tomorrow. Even the air held the scent of lemon polish and new books, the smell of a new school year, sweet with promise. “I’m going home. Nothing left to do that can’t be done tomorrow.”