2 A Season of Knives: A Sir Robert Carey Mystery

Read 2 A Season of Knives: A Sir Robert Carey Mystery Online

Authors: P. F. Chisholm

Tags: #Mystery, #rt, #Mystery & Detective, #amberlyth, #Thriller & Suspense, #Historical, #Literature & Fiction

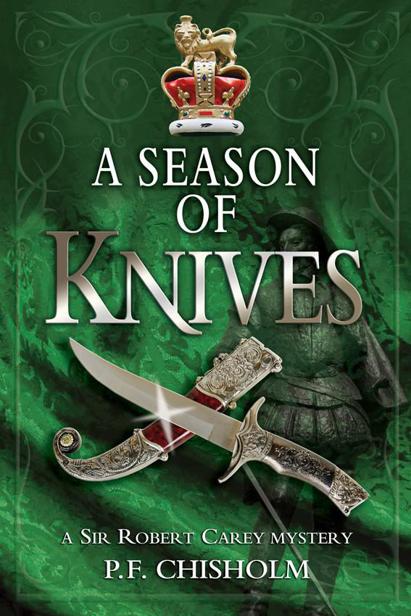

A Season of Knives

A Sir Robert Carey Mystery

P. F. Chisholm

www.Patricia-Finney.co.uk

Poisoned Pen Press

Copyright © 2000 by P. F. Chisholm

First Trade Paperback Edition 2000

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 99-068784

ISBN: 9781615954087 epub

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The historical characters and events portrayed in this book are inventions of the author or used fictitiously.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

Contents

To Melanie, with many thanks

Anyone who wants to know the true history of the Anglo-Scottish Borders in the Sixteenth Century should read George MacDonald Fraser’s superbly lucid and entertaining account: “The Steel Bonnets” (1971). Those who wish to meet the real Sir Robert Carey can read his Memoirs (edited by F.H. Mares, 1972) and some of his letters in the Calendar of Border Papers.

P.F. Chisholm writes You-Are-THERE! books.

A You-Are-THERE! book is a book that can make you feel the nap of Sir Robert Carey’s black velvet doublet beneath your fingertips. A You-Are-THERE! book can make you smell the sewer in the streets of Elizabethan Carlisle. A You-Are-THERE! book can make you taste the ale at Bessie Storey’s alehouse outside the Captain’s Gate at Berwick garrison, and a You-Are-THERE! book can make you hear the arquebuses firing at Netherby tower. A You-Are-THERE! book can make you feel like you’re ready to pack up and move THERE, if only you had a time machine.

THERE, in the case of P.F. Chisholm, is the nebulous and ever-changing border between Scotland and England in 1592, the thirty-fourth year of the reign of Good Queen Bess, five years after the Spanish Armada, fifty-one years after Henry VIII beheaded his last queen. Reivers with a high disregard for the allegiance or for that matter, the nationality of their victims roved freely back and forth across this border during this time, pillaging, plundering, assaulting and killing as they went.

Into this scene of mayhem and murder gallops Sir Robert Carey, the central figure of the mystery novels by P.F. Chisholm, including

A Famine of Horses

,

A Season of Knives

,

A Surfeit of Guns

and

A Plague of Angels

, brought to America (at last!) in paperback by Barbara Peters and the Poisoned Pen Press.

Sir Robert is the Deputy Warden of the West March, and his duty is to enforce the peace on the Border. Since everyone on the English side is first cousin once removed to everyone on the Scottish side, it is frequently difficult to tell his men which way to shoot. The first in the series,

A Famine of Horses

, begins with Sir Robert’s first day on the job and the murder of Sweetmilk Geordie Graham. In

A Season of Knives

Sir Robert is framed and tried for the murder of paymaster Jemmy Atkinson. On night patrol in

A Surfeit of Guns

, he uncovers a plot to smuggle arms across the Border. In the fourth book (and why hasn’t there been a fifth since, pray tell?),

A Plague of Angels

, Chisholm removes Sir Robert to London, where he encounters a bit player named Will Shakespeare involved in a plot that gives a whole new meaning to the phrase “bad actor.”

Sir Robert is as delightful a character as any who ever thrust and parried his way into the pages of a work of fiction, in this century or out of it. He is handsome, intelligent, charming, capable, as quick with a laugh as he is with a sword. He puts the buckle into swash. He puts the court into courtier; in fact, his men’s nickname for him is the Courtier.

The ensemble surrounding him is equally engaging. There is Sergeant Henry Dodd, Sir Robert’s second-in-command, who does “his best to look honest but thick.” There is Lord Scrope, Sir Robert’s brother-in law and feckless superior, who sits “hunched like a heron in his carved chair.” There is Philadelphia, Sir Robert’s sister, “a pleasing small creature with black ringlets making ciphers on her white skin.” There is Barnabus Cooke, Sir Robert’s manservant, who thinks longingly of the time when he “raked in fees from the unwary who thought, mistakenly, that the Queen’s favourite cousin might be able to put a good work in her ear.” And there is the Lady Elizabeth Widdrington, Sir Robert’s love and the wife of another man, who is “hard put to it to keep her mind on her prayers: Philadelphia’s brother would keep marching into her thoughts.” There is hand-to-hilt combat with villains rejoicing in names like Jock of the Peartree, and brushes with royalty in the appearance of King James of Scotland, who’s a little in love with Sir Robert himself.

And who can blame him? Sir Robert is imminently lovable, and these four books are a rollicking, roistering revelation of a time long gone, recaptured for us in vivid and intense detail in this series.

What is a You-Are-THERE! book?

It’s a book by P.F. Chisholm.

Dana Stabenow

email:

[email protected]

web site: http://

www.stabenow.com

Anyone who has read any history at all about the reign of Queen Elizabeth I has heard of at least one of Sir Robert Carey’s exploits—he was the man who rode 400 miles in two days from London to Edinburgh to tell King James of Scotland that Elizabeth was dead and that he was finally King of England. Carey’s affectionate and vivid description of the Queen in her last days is often quoted from his memoirs.

However, I first met Sir Robert Carey by name in the pages of George MacDonald Fraser’s marvellous history of the Anglo-Scottish borders,

The Steel Bonnets.

GMF quoted Carey’s description of the tricky situation he got himself into when he had just come to the Border as Deputy Warden, while chasing some men who had killed a churchman in Scotland.

“…about two o’clock in the morning I took horse in Carlisle, and not above twenty-five in my company, thinking to surprise the house on a sudden. Before I could surround the house, the two Scots were gotten into the strong tower, and I might see a boy riding from the house as fast as his horse would carry him, I little suspecting what it meant: but Thomas Carleton… told me that if I did not…prevent it, both myself and all my company would be either slain or taken prisoners.”

Perhaps you need to have read as much turgid 16th century prose as I have to realise how marvellously fresh and frank this is, quite apart from it being a cracking tale involving a siege, a standoff, and some extremely fast talking by Carey. And it really happened, nobody made it up; references in the

Calendar of Border Papers

suggest that Carey made his name with his handling of the incident.

It’s all the more surprising then that Robert Carey was the youngest son of Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon. Hunsdon was Queen Elizabeth’s cousin because Ann Boleyn’s older sister Mary was his mother. He was also probably Elizabeth’s half-brother through Henry VIII, whose official mistress Mary Boleyn was before the King clapped eyes on young Ann. (I have to say that one of the attractions of history to me is the glorious soap opera plots it contains.)

The nondescript William Carey who had supplied the family name by marrying the ex-official mistress, quite clearly did not supply the family genes. Lord Hunsdon was very much Henry VIII’s son—he was also, incidentally, Elizabeth’s Lord Chamberlain and patron to one William Shakespeare.

Robert Carey was (probably) born in 1560, given the normal education of a gentleman from which he says he did not much benefit, went to France for polishing in his teens, and then served at Court for ten years as a well-connected but landless sprig of the aristocracy might be expected to do.

Then in 1592 something made him decide to switch to full-time soldiering. Perhaps he was bored. Perhaps the moneylenders were getting impatient.

Perhaps he had personal reasons for wanting to be in the north. At any rate, Carey accepted the offer from his brother-in-law, Lord Scrope, Warden of the English West March, to be his Deputy Warden.

This was irresistable to me. In anachronistic terms, here was this fancy-dressing, fancy-talking Court dude turning up in England’s Wild West. The Anglo-Scottish Border at that time made Dodge City look like a health farm. It was the most chaotic part of the kingdom and was full of cattle-rustlers, murderers, arsonists, horse-thieves, kidnappers and general all-purpose outlaws. This was where they invented the word “gang”—or the men “ye gang oot wi’ “—and also the word “blackmail” which then simply meant protection money.

Carey was the Sheriff and Her Majesty’s Marshall rolled into one—of course, I had to give him a pair of pistols or dags, but they only fired one shot at a time. He was expected to enforce the law with a handful of horsemen and very little official co-operation. About the only thing he had going for him was that he could hang men on his own authority if he caught them raiding—something he seems to have done remarkably rarely considering the rough justice normally meted out on the feud-happy Border.

Even more fascinating, he seems to have done extremely well—and here I rely on reports and letters written by men who hated his guts. By 1603 he had spent ten years on the Border in various capacities, and got it quiet enough so he could take a trip down to London to see how his cousin the Queen was doing. Unfortunately for him, Carey also seems to have been too busy doing his job to rake in the cash the way most Elizabethan office-holders did.

So when Carey made his famous ride, he was a man of 42 with a wife and three kids, no assets or resources, facing immediate redundancy and possible bankruptcy. As he puts it himself with disarming honesty, “I could not but think in what a wretched estate I should be left… I did assure myself it was neither unjust nor unhonest for me to do for myself…. Hereupon I wrote to the King of Scots.”

What Carey did after his ride will have to wait for future books—or you could read his memoirs, of course. As GMF says, “Later generations of writers who had never heard of Carey found it necessary to invent him… for he was the living image of the gallant young Elizabethan.”