1968 (56 page)

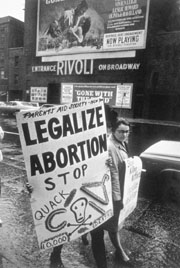

In 1968 NOW took on a variety of issues, including a key battle in New York over changing state law to legalize abortion. At the same time, they wanted Congress to produce an amendment to the Constitution guaranteeing equal rights for women. Such an amendment, the ERA, had been proposed and rejected by every Congress since 1923.

The feminist movement, like all the great movements of 1968, was rooted in the civil rights movement. Laws that enforced separate female status, a principle repeatedly upheld in the courts, were referred to as “Jane Crow laws.” Many feminists referred to NOW as the women’s NAACP, leading others to insist it was more radical—the women’s CORE or SNCC. Betty Friedan referred to women who pandered to male sexism as Aunt Toms.

Demonstration for abortion rights, New York, 1968

(Photo by Elliott Landy/Magnum Photos)

“There are striking parallels,” insisted Florence Henderson, a New York lawyer best known at the time for her defense of SNCC leader H. Rap Brown. “In court you often get a more patronizing attitude to blacks and women than white men: ‘Your Honor, I’ve known this boy since he was a child, his mother worked for my family. . . .’ ‘Your Honor, she is just a woman, she has three small children. . . .’ And I think white male society often takes the same attitude toward both: ‘If we want to give power to you O.K. But don’t act as if you are entitled to it.’ That’s too manly, too . . . white.”

The second wave of feminism might have broken sooner except that in the late 1950s and early 1960s the most talented, courageous, and idealistic women had joined the civil rights movement. Later in the sixties, the New Left was focused on ending the war, while white women in the civil rights movement for a long time felt it unseemly to raise issues of women’s rights, in the face of the far more serious abuse of blacks. Women, after all, were not being lynched or shot.

Among those white women from church backgrounds who went south and risked their lives with SNCC were Mary King and Sandra Cason—later to marry and divorce Tom Hayden and become Casey Hayden. Some of the older female SNCC workers, notably Ella Baker, were tremendous influences on the younger women. Baker, an important inspiration for Mary King and others, had started with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference as an adviser to Martin Luther King. But in 1960 she switched to SNCC. She said this about the SCLC:

I was difficult. I wasn’t an easy pushover. Because I could talk back a lot—not only could but did. And so that was frustrating to those who never had certain kinds of experience. And it’s a strange thing with men who were supposed to be “men about town”; if they had never known a woman who knew how to say No, and No in no uncertain terms, they didn’t know what to do sometimes. Especially if you could talk loud and had a voice like mine. You could hear me a mile away sometimes, if necessary.

In fact, Martin Luther King had a number of important issues in his own marriage completely aside from his womanizing. Coretta complained bitterly of being kept out of the movement. “I wish I was more a part of it,” she said in an interview. She envisioned a significant role for herself in the civil rights movement, and he had denied her that. This was a source of continual anger in their marriage and, according to some aides, often led to his being unable to go home at the end of a day. Dorothy Cotton, who worked closely with Martin Luther King in the SCLC, said, “Martin . . . was absolutely a male chauvinist. He believed that the wife should stay home and take care of the babies while he’d be out there in the streets. He would have a lot to learn and a lot of growing to do. I’m always asked to take the notes. I’m always asked to go fix Dr. King some coffee. I did it too.” To her it was the times. “They were sexist male preachers and grew up in a sexist world. . . . I loved Dr. King but I know that that streak was in him also.” Only after King’s death was Coretta Scott King free to emerge as an important voice for civil rights.

All of the 1960s movements—until NOW and other feminist groups became active—were run by men. Women in the SDS talked of how intimidating Tom Hayden and other male leaders were. An SDS brochure read, “The system is like a woman. You’ve got to fuck it to make it change.” Hayden in a recent interview said that part of the problem had been that “the women’s movement was dormant at the time SDS was started.” But he attributed the problem largely to his own “ignorance” and that of other leaders. Suzanne Goldberg, a leader in the Free Speech Movement and later Mario Savio’s first wife, said:

I was on the executive committee and the steering committee of the FSM. I would make a suggestion and no one would react. Thirty minutes later Mario or Jack Weinberg would make the same suggestion and everyone would react. Interesting idea. I thought maybe I’m not saying it well enough. I thought that for years. But then at the twenty-fifth anniversary of FSM, I ran into Jackie Goldberg and she said, “No, you were fine. It was classic. I used to use it in my street theater. Suzanne being ignored.”

Bettina Aptheker, another leader in the Free Speech Movement, said, “Women did most of the clerical work and fund-raising and provided food. None of this was particularly recognized as work, and I never questioned this division of labor or even saw it as an issue!”

Probably no group had a more equal distribution of labor than SNCC. SNCC work was physically arduous and always dangerous, and though it was sometimes argued that the leaders who got the media attention were all men, the work and the danger were equally divided. By 1968 SNCC’s problem was no longer attracting violence and media attention, it was surviving the violence. Once SNCC members realized, as did the Janet Rankin Brigade later, that less violence was used against them if they had women present, they wanted a strong female presence. Though they were constantly scared, beaten, arrested, intimidated, shot at, and attacked by snarling dogs—the women had to acknowledge that they were in less danger than the men, and the white women in less danger than the black women. The black men were in the most danger always. In October 1964 in the state of Mississippi, the civil rights movement suffered fifteen killings, four woundings, thirty-seven churches bombed or burned, and more than one thousand arrests.

In this one aspect, at least, SNCC was less sexist than the antiwar movement. David Dellinger was shocked, when organizing peace marches in 1967 and 1968, to find that pediatrician-turned–antiwar activist Benjamin Spock, and even Women’s Strike for Peace, one of the early women’s antiwar groups, urged that women and children not participate in demonstrations because of the threat of violence.

Among the books that were passed around SNCC, along with works by Frantz Fanon and Camus, one book that grew dog-eared, wilted, and coverless was Simone de Beauvoir’s condemnation of marriage and critique of women’s role in society,

The Second Sex.

Feminist ideas were slowly drifting into the movement. As Bettina Aptheker pointed out, before exposure to de Beauvoir and Friedan and a few others, a woman did not have the vocabulary to articulate her vague feelings of injustice.

In 1964 Mary King and Casey Hayden coauthored a memo to SNCC workers on women’s status in the movement. It was the SNCC style to float ideas in this way and later have meetings and talk them through. The memo consisted of a list of meetings from which women were excluded and projects in which eminently qualified women were overlooked for leadership roles.

Undoubtedly this list will seem strange to some, petty to others, laughable to most. The list could continue as far as there are women in the movement. Except that most women don’t talk about these kinds of incidents, because the whole subject is not discussable. . . .

The memo was anonymous because they feared ridicule. Bob Moses and a few others expressed admiration for it. Julian Bond smiled wryly about it, “non committal with his sidelong glance.” But by and large it was ridiculed. Mary King said that some who had figured out that she authored it “mocked and taunted” her. Late one moonlit night, King, Hayden, and a few others were sitting around with Stokely Carmichael. A compulsive entertainer, Carmichael was on, delivering a monologue ridiculing everyone and everything, keeping his audience laughing. Then he got to that day’s meeting and then to the memo, and staring at Mary King, he said, “What is the position of women in SNCC?” He paused as though waiting for an answer and said, “The position of women in SNCC is prone.” Mary King and the others doubled over with laughter.

In the decades since, the Carmichael quote is often cited as evidence of the sexist attitude in the radical civil rights movement. But the women who first heard it insist that it was intended and was received as a joke.

In 1965 they wrote another memo:

There seem to be many parallels that can be drawn between treatment of Negroes and treatment of women in our society as a whole. But in particular, women we’ve talked to who work in the movement seem to be caught up in a common-law caste system that operates, sometimes subtly, forcing them to work around or outside hierarchical structures of power which may exclude them. Women seem to be placed in the same position of assumed subordination in personal situations too. It is a caste system which, at its worst, uses and exploits women.

This second one that they signed became an influential document in the feminist movement, but of the forty black women, civil rights activists, friends, and colleagues to whom they sent it, not one responded.

The founding members of NOW—such as Friedan; East; Dr. Kathryn Clarenbach, a Wisconsin educator; Eileen Hernandez, a prominent lawyer; Caroline Davis, a Detroit United Auto Workers executive—were women with successful careers. Of their 1,200 members in 1968, many were lawyers, sociologists, and educators. There were also one hundred men, almost all of them lawyers. They hoped to reach out to women who did not have careers, to housewives and women working at low-status, underpaid jobs. But the new wave, much like the antiwar movement, was starting among a well-educated elite who had shed the conventional prejudice of society.

In 1968 a feminist was still denigrated, a woman with a problem, something wrong with her, probably unattractive. Feminists—bra burners—it was believed, were bitter women who opposed beauty because they didn’t have it. Disturbing that stereotype was the head of the New York chapter of NOW, Ti-Grace Atkinson, a twenty-nine-year-old unmarried woman from Louisiana who, it was unfailingly pointed out in every newspaper account, was “attractive,” “good-looking,” or, in the words of

The New York Times,

“softly sexy.”

In 1968 the least attempts at reforming marriage were considered radical by the general population. It was still considered a radical feminist act for a married woman not to take her husband’s name. Like Simone de Beauvoir, the tremendously influential French feminist who lived with, but never married Sartre, many of the sixties feminists were at best distrustful of the institution of marriage. Atkinson said, “The institution of marriage has the same effect the institution of slavery had. It separates people in the same category. It disperses them, keeps them from identifying as a class. The masses of slaves didn’t recognize their condition either. To say that a woman is really ‘happy’ with her home and kids is as irrelevant as saying that the blacks were ‘happy’ being taken care of by the ol’ Massa. She is defined by her maintenance role. Her husband is defined by his productive role. We’re saying that all human beings should have a productive role in society.” Her own views on marriage were shaped by having been married at seventeen. She divorced, got an arts degree at the University of Pennsylvania, became the first director of the Philadelphia Institute of Contemporary Art, got a graduate degree at Columbia in philosophy. She said de Beauvoir’s

The Second Sex

“changed my life.” She wrote to de Beauvoir, who suggested she get involved with an American group. That was when Atkinson found the nascent NOW.

In France, land of de Beauvoir, the feminist movement is also said to have been born in 1968. Yet de Beauvoir’s

The Second Sex

was first published in France in 1949 and by 1968 had influenced a large part of an entire generation of women whose daughters were now reading it. The year 1968 was when activists formed groups pressuring the government to legalize abortion and widen access to the pill, which was available only by prescription. Women were refused prescriptions by doctors for a variety of reasons, including the arbitrary verdict that they were too young.

In Germany, too, the feminist movement can be traced to 1968, to a Frankfurt conference of the German SDS, when Helke Sander declared the equality of the sexes and demanded that future planning take into account the concerns of women. When the conference refused to have an in-depth discussion of Sander’s proposal, angry women began pelting men with tomatoes. But in fact women’s groups had been founded in several cities before this incident, the first one in Berlin in January 1968.

De Beauvoir, with her famously long and deep relation with Sartre, said that people should be joined by love and not legal sanctions. Atkinson and many other American feminists in 1968 were saying that in order for women and men to have equal status, children would have to be raised communally. The commune was becoming a popular solution. Communes were springing up all over the United States. Some child development experts who had studied the kibbutz system in Israel were unimpressed. Dr. Selma Fraiberg at the University of Michigan’s Child Psychiatric Hospital told

The New York Times

in a 1968 interview that her studies of children raised on a kibbutz produced what she called “a bunch of cool cookies”—cold, unfriendly people. But women in communes began to complain that there was a gender-based caste system there as well, that the women would do the cleaning while the men meditated.