1968 (20 page)

Now established as one of the leading “hippies” of New York’s East Village, Hoffman joined a group called the Diggers, founded by a group of actors from San Francisco, the San Francisco Mime Troupe. He explained the difference between a Digger and a hippie in an essay titled “Diggery Is Niggery” for a publication called

Win.

Diggers, he said, were hippies who had learned to manipulate the media instead of being manipulated by them. “Both are in one sense a huge put-on,” he wrote.

The Diggers were named after a seventeenth-century English free land movement that preached the end of money and property and inspired the idea of destroying money and giving everything away for free as revolutionary acts. Hoffman staged a “sweep-in” on Third Street in the East Village, usually one of Manhattan’s dirtiest streets. The police did not know how to respond when Hoffman and the Diggers took to the block with brooms and mops. One even walked up to a New York City cop and started polishing his badge. The policeman laughed. Everyone laughed, and the

Village Voice

reported that the “sweep-in” was “a goof.” Later that year Hoffman staged a “smoke-in” in which people went to Tompkins Square Park and smoked marijuana, which was pretty much what everyone had been doing anyway.

“A modern revolutionary group,” Hoffman explained, “headed for the television station, not for the factory.”

Hoffman’s partner and competitor was Jerry Rubin, born in 1938 1968 of Rubin and Hoffman rolling on the floor in drug-induced stupors while founding the Yippie! movement is exactly the opposite of what it appears to be. Instead of being the embarrassing reality leaked to the press by some disloyal insider, it was in fact a planted story. In reality, Rubin and Hoffman had given a great deal of sober thought to the creation of the movement. Hoffman, in his “free” period, wanted to call the group the Freemen. In fact, his first book,

Revolution for the Hell of It,

was published in 1968 under the nom de plume Free. But after long discussion, the Freemen lost out to Yippie! It wasn’t until later in the year that it occurred to them to say it stood for Youth International Party.

No one was certain how seriously to take Abbie Hoffman, and that was his great strength. One story tells much about the elusive clown of the sixties. In 1967, Hoffman got married for a second time. The June 8 “wed-in” was also publicized in the

Village Voice,

which said, “Bring flowers, friends, food, fun, costumes, painted faces.” The couple was to be joined “in holy mind blow”—dressed in white with garlands in their hair. The I Ching, the Chinese Book of Change that was used to interpret the future three thousand years ago and in 1968 reemerged as popular mysticism, was read at the ceremony. The groom was visibly under the influence of marijuana and giggled uncontrollably.

Time

magazine covered the wed-in for its July 1967 issue on hippies but did not mention the “beflowered couple” by name. Abbie Hoffman was not a widely known name until 1968. But after the wed-in, without any publicity, the bridal couple went off to the decidedly bourgeois Temple Emanu-El on Manhattan’s affluent Upper East Side, where Rabbi Nathan A. Perilman quietly performed a traditional Reform Jewish wedding.

Jews in disproportionate numbers were active in student movements in 1968 not only in Poland, but in the United States and France. At Columbia and the University of Michigan, two of SDS’s most active campuses, SDS was more than half Jewish. When Tom Hayden first went to the University of Michigan, he noted that the only political activists were Jewish students from leftist families. Two-thirds of the white Freedom Riders were Jewish. Most of the leaders of the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley were Jewish. Mario Savio, the notable exception, said:

I’m not Jewish, but I saw those pictures. And those pictures were astonishing. Heaps of bodies. Mounds of bodies. Nothing affected my consciousness more than those pictures. And those pictures had on me the following impact, which other people maybe came to in a different way. They meant to me that everything needed to be questioned. Reality itself. Because this was like opening up your father’s drawer and finding pictures of child pornography, with adults molesting children. It’s like a dark, grotesque secret that people had that at some time in the recent past people were being incinerated and piled up in piles. . . . Those pictures had an impact on people’s lives. I know they had an impact on mine, something not as strong but akin to a “never again” feeling which Jews certainly have had. But non-Jews had that feeling, too.

People born during and directly after World War II grew up in a world transformed by horror, and this made them see the world in a completely different way. The great lesson of Nazi genocide for the postwar generation was that everyone has an obligation to speak up in the face of wrong and that any excuse for silence will, in the merciless hindsight of history, appear as pathetic and culpable as the Germans in the war crimes trials, pleading that they were obeying orders. This was a generation that as children learned of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Children who were told constantly throughout their childhood that at any moment the adults might decide to have a war that would end life on earth.

While an older generation justified the nuclear bombing of Japan because it had shortened the war, the new generation once again, as children, had seen the pictures and they viewed it very differently. They had also seen the mushroom clouds of nuclear explosions on television because the United States still did aboveground testing. Americans and Europeans, both Eastern and Western, grew up with the knowledge that the United States, which was continuing to build bigger and better bombs, was the only country that had ever actually used one. And it talked about doing it again, all the time—in Korea, in Cuba, in Vietnam. The children born in the 1940s in both superpower blocs grew up practicing covering themselves up in the face of nuclear attack. Savio recalled being ordered under his desk at school: “I ultimately took degrees in physics so even then I asked myself questions like ‘Will this actually do the job?’ ”

Growing up during the cold war had the same effect on most of the children of the world. It made them fearful of both blocs. This was one of the reasons European, Latin American, African, and Asian youth were so quick and so resolute in their condemnation of U.S. military action in Vietnam. By and large, theirs was not a support of communists, but a distaste for either bloc imposing its power. To American youth, the execution of the Rosenbergs, the lives ruined by Senator Joseph McCarthy’s hearings, taught them to distrust the U.S. government.

Youth around the globe saw the world being squeezed by two equal and unsavory forces. American youth had learned that it was important to stand up to both the communists and the anticommunists. The Port Huron Statement recognized that communism should be opposed: “The Soviet Union, as a system, rests on the total repression of organized opposition, as well as a vision of the future in the name of which much human life had been sacrificed, and numerous small and large denials of human dignity rationalized.” But according to the Port Huron Statement, anticommunist forces in America were more harmful than helpful. The statement cautions that “an unreasoning anti-Communism has become a major social problem.”

This first started to be expressed in the 1950s with the film characters portrayed by James Dean, Marlon Brando, and Elvis Presley, and the beat generation writings of Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. But the feeling grew in the 1960s. The young invested hope in John Kennedy, largely because he too was relatively young—the second youngest president in history replacing Eisenhower, who at the time was the oldest. The inauguration of Kennedy in 1961 was the largest change of age ever at the White House, with almost thirty years’ difference between the exiting and entering presidents. But even under Kennedy, young Americans experienced the Cuban missile crisis as a terrifying experience and one that taught that people in power play with human life even if they are young and have a good sense of humor.

Most of the people who arrived at college campuses in the mid-1960s had a deep resentment and distrust of any kind of authority. People in positions of authority anywhere on the political spectrum were not to be trusted. That is why there were no absolute leaders. The moment a Savio or Hayden declared himself leader, he would have lost all credibility.

There was something else that was different about this generation. They were the first to grow up with television, and they did not have to learn how to use it, it came naturally, the same way children who grew up with computers in the 1990s had an instinct for it that older people could not match with education. In 1960, on the day of Eisenhower’s last news conference, Robert Spivack, a columnist, asked the president if he felt the press had been fair to him during his eight years in the White House. Eisenhower answered, “Well, when you come down to it, I don’t see much what a reporter could do to a president, do you?” Such a sentiment would never again be heard in the White House. Kennedy, born in 1917, was said to have understood television, but it was really his brother Robert, eight years younger, who was the architect of the Kennedy television presidency.

By 1968 Walter Cronkite had reached what for him was a disturbing conclusion, that television was playing an important part not only in the reporting of events, but in the shaping of them. Increasingly around the world, public demonstrations were being staged, and it seemed clear to him that they were being staged for television. Street demonstrations are good television. They do not even need to be large, they need only enough people to fill the frame of a television camera.

“You can’t put that as the only reason they were in the streets; demonstrations took place before television, but this was an added incitement to demonstrate,” Cronkite reflected decades later. “Particularly as television communications in the world showed them that this was successful in different communities, they obviously felt, well, that’s the way you do it. And so it was epidemic around the world.”

This generation, with its distrust of authority and its understanding of television, and raised in the finest school of political activism, the American civil rights movement, was uniquely suited to disrupt the world. And then they were offered a war they did not want to fight and did not think should be fought. The young people of the generation, the ones who were in college in 1968, were the draftees. The Haydens and Savios, and Abbie Hoffmans, too young for Korea and too old for Vietnam, had not faced a draft. These younger members of the sixties generation, the people of 1968, had a fury in them that had not been seen before.

CHAPTER 6

HEROES

Let us decide not to imitate Europe; let us combine our muscles and our brains in a new direction. Let us try to create the whole man, whom Europe has been incapable of bringing to triumphant birth.

—F

RANTZ

F

ANON,

The Wretched of the Earth,

1961

1968

WAS SUPPOSED TO BE

Johnson’s year. As winter thawed toward spring, every one of the numerous men who were dreaming of the White House was calculating his chances of beating the incumbent president. And in every one of those hypothetical contests, Johnson was favored to win. But even those not running for president were running against Johnson. Martin Luther King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference announced a plan to have hundreds of thousands of poor people, white and black, march on Washington in the spring. Poverty, instead of being hidden, would be displayed openly and put on television. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy, the number two leader in the movement, said, “We’re going up there to talk to LBJ, and if LBJ doesn’t do something about what we tell him, we’re going to put him down and get us another one who will.”

But by March 12, 1968 was no longer necessarily Johnson’s year. That day Johnson won his first primary, an easy contest in New Hampshire in which the incumbent was opposed only by the improbable senator Eugene McCarthy, the candidate

Life

magazine one month earlier had labeled “a conundrum.” The shock was that the president on that snowy New Hampshire day had defeated the conundrum by a mere 230 votes. Around the world, the news was reported as though the unknown senator had just been elected president, or at the very least had defeated Johnson. While Warsaw students were fighting police in the streets and Czechs were drifting ever further from Soviet control, the Soviet Party newspaper,

Pravda,

said that the primary results showed that the Vietnam War “has become the main and decisive question of the 1968 presidential election.” In Spain, where the University of Madrid was closed, the Catholic newspaper

Ya

predicted that the November elections would “turn upside down for Johnson.” In Rome, where students had shut down the university, the left-wing press was declaring a victory for the antiwar movement.

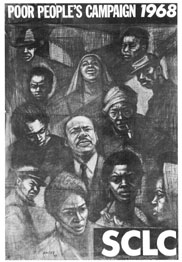

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, last campaign, 1968

(Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture)

Nelson Rockefeller, governor of New York, who was not on the Republican ballot in New Hampshire, conducted a disappointing write-in campaign in which he garnered only 10 percent of the vote. After the primary, he announced his decision not to run, leaving the Republican field open to what to many was the unthinkable: another Nixon nomination. Nixon had little time to gloat, because Robert Kennedy announced that he too was a candidate, raising the terrifying specter in Nixon’s mind of a rerun of the campaign that had almost ended his career—another Nixon-Kennedy showdown. But first Kennedy would have to unseat the incumbent. On March 31 came the bombshell: President Johnson went on television and announced, “I shall not seek and I will not accept the nomination of my party as your president.”

Suddenly the front-running Democratic incumbent was out of the race, and no one was sure what would happen next. “It was America that was on a trip; we were just standing still,” said Abbie Hoffman. “How could we pull our pants down? America was already naked. What could we disrupt? America was falling apart at the seams.”

Historians have debated Johnson’s reasons ever since. McCarthy supporters and antiwar activists claimed victory—that they had convinced the president he could not win. In subsequent years, it has been revealed that Johnson’s hawkish cabinet had advised him that escalation of the war was politically impossible and the war was militarily unwinnable. Johnson did, along with his resignation, announce a limited halt to bombing and the intention to seek peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese. But the president was not acting like the well-known LBJ. There had been good reasons to believe he might have won reelection. It could have been that the snowstorm had kept overconfident Johnson supporters home the day of the primary and the narrowness of his victory was only a fluke. Even if New Hampshire did mean real trouble ahead, Johnson did not usually avoid tough political contests. After the New Hampshire primary,

The Times

of London predicted the result would “anger” Johnson and “should activate the politician within him.” Some have said that his wife urged him not to run.

The New York Times

speculated that the primary inducement was that the war was going badly.

From March 8 to 14, the world experienced yet another international debacle caused by the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. The war was costing the United States about $30 billion annually. And the $3.6 billion balance of payments deficit was considered so enormous that such measures as travel curbs were viewed as pointless Band-Aids. The United States was financing the war with gold reserves, which were now at only half of their post–World War II high of $24.6 billion. The value of the dollar was fixed to gold, and speculators looking at these figures concluded that the United States would not be able to maintain the fixed price of gold at $35 an ounce. The United States, according to the theory, would not have sufficient reserves to sell at $35 to all buyers, which would force up the price of gold. Those who held gold would make enormous profits. The same thing had happened to sterling in November 1967 when the British devalued the pound. Gold speculators went on a buying spree that set off a panic that the press called “the biggest gold rush in history.” More than two hundred tons of gold worth $220 million changed hands on the London gold market, setting a new single-day record. So much gold was going into Switzerland that one bank had to reinforce its vaults for the added weight. Economists around the world were predicting disaster. “We’re in the first act of a world depression,” said British economist John Vaizey.

While the world angrily watched America’s Vietnam spending destabilize the global economy, the war itself ground on uglier than ever. On March 14 the U.S. command reported that 509 American servicemen were killed and 2,766 had been wounded in the past week, bringing total casualties since January 1, 1961, to 139,801, of whom 19,670 had been killed. This did not approach the 33,000 dead in three years of fighting in Korea. But for the first time the total casualties, including wounded, was higher in Vietnam than in Korea.

On March 16 the 23rd Infantry Division, the so-called Americal Division, was fighting in central Vietnam along the murky brown South China Sea in the village of Son My, where they slaughtered close to five hundred unarmed civilians that day. Much of the killing was in one hamlet called My Lai, but the action took place throughout the area. Elderly people, women, young boys and girls, and babies were systematically shot while some of the troops refused to participate. One soldier missed a baby on the ground in front of him two times with a .45-caliber pistol before he finally hit his target, while his comrades laughed at what a bad shot he was. Women were beaten with rifle butts, some raped, some sodomized. The Americans killed the livestock and threw it in the wells to poison the water. They threw explosives into the bomb shelters under the houses where villagers had tried to escape. Those who ran out to avoid the explosives were shot. The houses were all burned. Tom Glen, a soldier in the 11th Brigade, wrote a letter to division headquarters reporting the crimes and waited for a response.

Whatever the reason for Johnson’s withdrawal from the presidential race, it created a strange political reality. The Democrats had Minnesota’s Eugene McCarthy, the peace candidate who had barely bothered to articulate any program beyond the single issue, and New York senator Robert Kennedy, who, according to the February issue of

Fortune

magazine, was more disliked by business leaders than any other candidate since the 1930s. The youth of 1968, famously alienated and removed from conventional politics, suddenly had two candidates they admired vying for the nomination of the ruling party. The fact that these two politicians, both from the traditional political establishment, had managed to earn the faith and respect of young people who scoffed at the labels “Democrat” and “liberal” was remarkable. No one believed they would have the field to themselves for long. The political establishment would run its own candidate, no doubt Vice President Hubert Humphrey, but for the moment it was exhilarating. A McCarthy ad showing the senator surrounded by youth carried the headline

OUR CHILDREN HAVE COME HOME.

Suddenly there’s hope among our voting people.

Suddenly they’ve come back into the mainstream of American life. And it’s a different country.

Suddenly the kids have thrown themselves into politics, with all their fabulous intelligence and energy. And it’s a new election.

When the following year Henry Kissinger became Nixon’s security adviser, he gave an interview to

Look

magazine in which he demonstrated his extraordinary ability to speak with authority while being completely wrong.

I can understand the anguish of the younger generation. They lack models and they have no heroes, they see no great purpose in the world. But conscientious objection is destructive of a society. The imperatives of the individual are always in conflict with the organization of society. Conscientious objection must be reserved for only the greatest moral issue, and Vietnam is not of this magnitude.

It was clear that Kissinger was incapable of understanding “the anguish of the younger generation.” To begin with, this was a generation with a long list of heroes, though neither Kissinger nor those he admired were to be found on this list. For the most part, the list did not include politicians, generals, or leaders of state. Young people all over the world had these heroes in common, and there was an excitement about the discovery that like-minded people could be found all over the world. For Americans, this was an unusually international perspective. It could be argued that because of the birth of satellite communications and television, this was the first global generation. But subsequent generations have not been this cosmopolitan.

What was also unusual for Americans was that so many of the revered figures were writers and intellectuals. This is perhaps because to a very large extent theirs was a movement from the universities. Perhaps the single most influential writer for young people in the sixties was Algerian-born French Nobel Prize laureate Albert Camus, who died in 1960 in an automobile crash at age forty-seven, just as what should have been his best decade was beginning. Because of his 1942 essay, “The Myth of Sisyphus,” in which he argued that the human condition was fundamentally absurd, he was often associated with the existential movement. But he refused to consider himself part of that group. He was not a joiner, which is one of the reasons he was more revered than the existentialist and communist Jean-Paul Sartre, even though Sartre lived through and even participated in the sixties student movements. Camus, who worked with the Resistance against the Nazi occupiers of France editing an underground newspaper,

Le Combat,

often wrote from the perspective of a moral imperative to act. His 1948 novel,

The Plague,

is about a doctor who risks his life and family to rid his community of a sickness he discovers. In the 1960s, students all over the world read

The Plague

and interpreted it as a call to activism. Mario Savio’s famous 1964 speech, “There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious . . . you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears . . . and you’ve got to make it stop,” sounds like a line from

The Plague.

“There are times when the only feeling I have is one of mad revolt,” Camus wrote. American civil rights workers read Camus. His books were passed from one volunteer to the next in SNCC. Tom Hayden wrote that he considered Camus to be one of the great influences in his decision to leave journalism and become a student activist. Abbie Hoffman used Camus to explain in part the Yippie! movement, referring to Camus’s words in

Notebooks

: “The revolution as myth is the definitive revolution.”

By 1968 there was another intellectual it seemed everybody wanted to quote: Marxist-Hegelian revisionist revolutionary Herbert Marcuse. His most appealing idea was what he called “the great refusal,” the time to say “No, this is not acceptable”—another idea that was expressed in Savio’s “odious machine” speech. Marcuse, a naturalized American citizen who had fled the Nazis, was on the faculty of Brandeis when Abbie Hoffman had been a student there, and Hoffman was enormously influenced by him, especially by his book

Eros and Civilization,

which talked about guilt-free physical pleasure and warned about “false fathers, teachers, and heroes.” The most talked-about Marcuse book of the late sixties,

One-Dimensional Man,

was published in 1964. It denounced technological society as shallow and conformist and put into the carefully orchestrated discipline of German philosophy all of the sentiments of the 1950s James Dean–style rebels and the 1960s student revolutionaries.

The New York Times

called Marcuse “the most important philosopher alive.”