(1/20) Village School (12 page)

Read (1/20) Village School Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #Country life, #Country Life - England, #Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place), #Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place)

Jasmine Villa had been built some eighty years ago by a prosperous retired tradesman from Caxley. His grandson still ran the business there, but let this property to Mr and Mrs Pratt for a rental so small that it was next to impossible for him to keep the house in adequate repair.

It was square and grey with a slated roof. A verandah ran across its width, and over this in the summer-time grew masses of the shrub which gave the house its name. So dilapidated was this iron verandah that its curling trellis-work and the jasmine appeared to give each other much-needed mutual support. A neat black and white tiled path, edged with undulating grey stone coping, like so many penny buns in rows, led from the iron gate to the front door. It was an incongruous house to find in this village. It might have been lifted bodily from Finsbury Park or Shepherd's Bush and dropped down between the thatched row of cottages belonging to Mr Roberts' farm on the one side, and the warm red bulk of 'The Beetle and Wedge' on the other.

Mrs Pratt, a plain cheerful woman in her thirties, opened the door to us. Her face always gleams like a polished apple, so tight and shiny is her well-scrubbed skin.

'Come into the front room,' she invited us, 'I'm afraid the fire's not in—we live at the back mostly, and my husband's just having his tea out there.' An appetizing smell of grilled herring wreathed around us as she spoke.

I explained why I had come and introduced the two to each other. Mrs Pratt began to rattle away about cooked breakfasts, bathing arrangements, washing and ironing, retention fees, door keys and all the other technical details that landladies need to discuss with prospective tenants, while Miss Gray listened and nodded and occasionally asked a question.

The room was lit by a central hanging bulb. It was very cold and I was glad that Mrs Pratt's business methods were so brisk that I might reasonably get back to my fire within half an hour.

Against one wall stood an upright piano on which Mrs Pratt practised her church music. A copy of'The Crucifixion' was open on the stand. Mr Annett evidently started practising his Good Friday oratorio in good time. Two large photographs dominated the top. One showed a wasp-waisted young woman, with a bustle, leaning against a pedestal, in a sideways-bend position which must have given her ribs agony as her corsets could not have failed to dig in cruelly at the top. The same young woman appeared in the second photograph. She was in a wedding dress, and stood behind an ornately carved chair, in which sat a bewildered little man with a captured expression. One large capable hand rested on his shoulder, the other grasped the chair-back, and on her face was a look of triumph. Between the two photographs was a long green dish of thick china, shaped like a monstrous lettuce leaf, with three china tomatoes clustering at one end.

I turned my fascinated gaze to the sideboard as Mrs Pratt's voice rose and fell. Here there was more distorted pottery to the square foot of sideboard top than I have ever encountered. Toby jugs jostled with teapots shaped like houses, jam pots shaped like beehives, apples and oranges, jugs like rabbits and other animals, and one particularly horrid one taking the form of a bird—the milk coming from the beak as one grasped the tail for a handle. A shiny black cat, with a very long neck, supported a candle on its head and leered across at a speckled china hedgehog whose back bristled with coloured spills. A bloated white fish with its mouth wide open had ashes' printed down its back and faced a frog who was yawning, I imagine, for the same purpose. At any minute one imagined that Disneyish music would start to play and these fantastic characters would begin a grotesque life of their own, hobbling, squeaking, lumbering, hinnying—poor deformed players in a nightmare.

'I do like pretty things,' said Mrs Pratt complacently, following my gaze. 'Shall we go up and see the bedroom?'

It was surprisingly attractive, with white walls and velvet curtains—'bought at a sale,' explained Mrs Pratt—which had faded to a gentle blue. The room, like the one below it which we had just left, was big and lofty, but much less cluttered with furniture. Miss Gray seemed pleased with it. There were only three drawbacks, and they were all easily removed; a plaster statuette of a little girl with a pronounced spinal curvature and a protruding stomach, who held out her skirts winsomely as she gazed out of the window; and two pictures, equally distressing.

One showed a generously-proportioned young woman with eyes piously upraised. She was lashed securely to a stake set in the midst of a raging river, for what reason was not apparent. There were some verses, however, beneath this picture and I determined to read them when visiting Miss Gray in the future. The other picture was even more upsetting, showing a dog lying in a welter of blood, the whites of its eyes showing frantically. Its young master, in a velvet suit, was caressing it in farewell. I knew I should never hope for a wink of sleep in the presence of such scenes and only prayed that Miss Gray might not be so easily affected.

We followed Mrs Pratt down the stairs to the front door. Snowflakes whirled in as she opened it.

'I will let you know definitely by Monday,' said Miss Gray. 'Will that do?'

'Perfectly, perfectly!' answered Mrs Pratt happily, 'and we can always alter anything you know—I mean, if you want to bring your own books or pictures we could come to some arrangement——'

We nodded and waved our way through the snowflakes down to the gate and into the lane. The snow was beginning to settle and muffled the sounds of our footsteps.

'I suppose,' Miss Gray began diffidently, 'that there is nowhere else to go?'

'I don't know of any other place,' I replied, and went on to explain how difficult it is to get suitable lodgings for a single girl in a village. The cottages are too small and are usually overcrowded as it is, and the people who have large houses would never dream of letting a room to a schoolteacher. It is a very serious problem for rural schools to face. It is not easy for a girl to find suitable companionship in a small village, and if it is any considerable distance from a town there may be very little to keep her occupied and happy in such a restricted community. It is not surprising that young single women, far from their own homes, do not stay for any length of time in country schools.

'Those pictures must go!' said Miss Gray decidedly, as we stood sheltering against Mr Roberts's wall waiting for the bus.

'They must,' I agreed, with feeling.

'She's asking two pounds ten a week,' pursued Miss Gray, 'which seems fair enough I think.' I thought so too, and we were busy telling each other how much better it would all look with a fire going and perhaps some of the china tactfully removed 'for safety's sake,' and one's own books and possessions about, when the bus slithered to a stop in the snow. Miss Gray boarded it, promising to telephone to me, and was borne away round the bend of the lane.

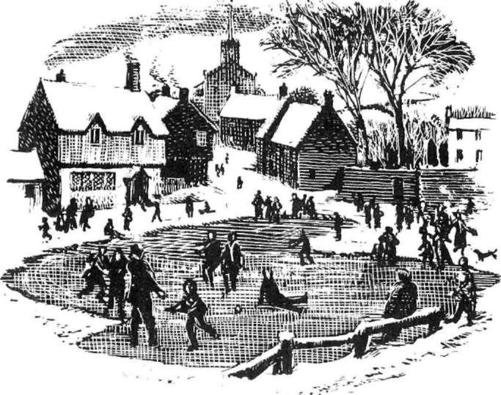

12. Snow and Skates

I

T

snowed steadily throughout the night and I woke next morning to see a cold pallid light reflected on the ceiling from the white world outside. It was deathly quiet everywhere. Nothing moved and no birds sang. The school garden, the playground, the neighbouring fields and the distant majesty of the downs were clothed in deep snow; and although no flakes were falling in the early morning light, the sullen grey sky gave promise of more to come.

Mrs Pringle was spreading sacks on the floor of the lobby when I went over to the school.

'Might save a bit,' she remarked morosely, 'though with the way children throws their boots about these days, never thinking of those that has to clear up after them, I expect it's all love's labour lost.' She followed me, limping heavily, into the schoolroom. I prepared for the worst.

'This cold weather catches my bad leg cruel. I said to Pringle this morning, "For two pins I'd lay up today, but I don't like to let Miss Read down." He said I was too good-hearted, always putting other people first—but I'm like that. Have been ever since a girl; and a good thing I did come!' She paused for dramatic effect. I knew my cue.

'Why? What's gone wrong?'

'The stove in the infants' room.' Her smile was triumphant. 'Something stuck up the flue, shouldn't wonder. That Mrs Finch-Edwards does nothing but burn paper, paper, paper on it! Never see such ash! And as for pencil sharpenings! Thick all round the fireguard, they are! Miss Clare, now, always sharpened on to a newspaper, and put it all, neat as neat, in the basket, but I wouldn't like to tell you some of the stuff I've riddled out of that stove at nights since madam's been in there!'

She buttoned up her mouth primly and gave me such a dark look that one might have thought she'd been fishing charred children's bones out of the thing. I assumed my brisk tone.

'It won't light at all?'

'Tried three times!' attested Mrs Pringle, with maddening complacency. 'Fair belches smoke, pardon the language! Best get Mr Rogers to it. Mr Willet's got no idea with machinery. Remember how he done in the vicar's lawn-mower?'

I did, and said we must certainly get Mr Rogers to come and look at the stove. Mrs Pringle noticed the use of the first person plural and hastened to extricate herself.

'If my leg wasn't giving me such a tousling I'd offer to go straight away, miss, as you well know. For as Pringle says, never was there such a one for doing a good turn to others, but it's as much as I can do to drag myself round now. As you can see!' she added, moving crabwise to straighten the fire-irons, and flinching as she went.

'The children will all have to be in here together this morning, so I shall go down myself,' I said. 'With this weather, and the epidemic still flourishing, I doubt if we shall get many at school in any case.'

'If only he was on the 'phone,' said Mrs Pringle, 'it would save you a walk. But there, when you're young and spry a walk in the snow's a real pleasure!'

She trotted briskly back to the lobby, the limp having miraculously vanished, as she heard children's voices in the distance.

'And don't bring none of that dirty old snow in my clean school,' I heard her scolding them. 'Look where you're treading now—scuffling about all over! Anyone'd think I was made of sacks.'

There were only eighteen children in school that day. Little wet gloves, soaked through snowballing, and a row of wet socks and steaming shoes lined the fire-guard round the stove in my room.

I left Mrs Finch-Edwards to cope with a test on the multiplication tables and set out to see Mr Rogers who is the local blacksmith and odd-job man.

His forge is near Tyler's Row and I walked down the deserted village street thinking how dirty the white paint, normally immaculate, of Mr Roberts' palings looked against the dazzle of the snow. I passed Mrs Pratt's house and 'The Beetle and Wedge,' where I caught a glimpse of Mrs Coggs on her knees, with a stout sack for an apron and a massive scrubbing-brush in her hand.

'Sut!' said Mr Rogers, when I told him. 'Corroded sut!' He was hammering a red-hot bar, as he spoke, and his words jerked from him to an accompanying shower of sparks. 'That's it, you'll see! Corroded sut in the flue-pipe!' He suddenly flung the bar into a heap of twisted iron in a dark recess, and drawing a very dirty red handkerchief from his pocket, he blew his nose violently. I waited while he finished this operation, which involved a great deal of polishing, mopping and finally flicking of the end of his flexible nose, from side to side. At last he was done, and he stuffed his handkerchief away, with some post-operative sniffs, saying:

'Be up there during your dinner hour, miss; clobber and all! Nothing but sut, I'll lay!'

The schoolroom was cheerful and warm to return to. There was a real family feeling in the air this morning, engendered by the small number of children and the wider range of age, from the five-year-olds like Joseph and Jimmy to the ten-year-old Cathy and John Burton.

They were sitting close to the stove, on which the milk saucepan steamed, with their mugs in their hands. After the bleak landscape outside this domestic interior made a comforting picture. They chattered busily to each other, recounting their adventures on the perilous journey to school, and tales grew taller and taller.

'Why, up Dunnett's there's a tractor buried, and you can't see nothing of it, it's that deep!'

'You ought to see them ricks up our way! Snow's right up the top, one side!'

'Us fell in a drift outside the church where that ol' drain is! Poor ol' Joe here he was pretty near up to his armpits, wasn't you? Didn't half make me laugh!'

'They won't run no more Caxley buses today, my dad said. It's higher'n a house atween here and Beech Green!'

Their eyes were round and shining with excitement as they sought to impress each other. Sipping and munching their elevenses, they gossiped away, heroes all, travellers in a strange world today, whose perils they had overcome by sheer intrepidity.

Playtime over, I brought out the massive globe from the cupboard and set it on the table. I told them about hot countries and cold, about tropical trees and steaming jungles, and about vast tracts of ice and snow, colder and more terrifying than any sights they had seen that morning. Together we ranged the world, while I tried to describe the diverse glories of tropic seas and majestic mountain ranges, the milling vivid crowds of the Indian cities and the lonely solitude of the trapper's shack; all the variety of beauty to be found in our world, here represented by this fascinating brass-bound ball in a country classroom.