(11/20) Farther Afield (16 page)

Read (11/20) Farther Afield Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Pastoral Fiction, #Crete (Greece), #Country Life - England, #General, #Literary, #Country Life, #England, #Fiction, #Villages - England

'Of course, it will have its brighter side for you,' said Mrs Partridge. 'There won't be so many children next term, which will be a help with Mrs Pringle laid up.'

'I suppose I'd better look for someone else to stand in.'

'Well, Minnie Pringle won't be able to come. There's a new baby due, any minute now.'

'That's a relief. I shan't feel obliged to ask her. After ten minutes of Minnie's company, I'm nearly as demented as she is.

'If the worst comes to the worst,' said the vicar, 'the older children must just turn to and help with the cleaning. Do it yourself, you know,' he added, beaming with pride at being so up-to-the-minute.

Mr and Mrs Mawne, it appeared, were in Scotland for a holiday, and I felt somewhat relieved. It would give me a breathing space before having to confess that I had no photographs of the Cretan hawk. The new people at Tyler's Row were repainting their house. Miss Waters' bad leg was responding to Dr Martin's liniment, and her sister had offered to embroider a new altar cloth.

At this stage, an enormous yawn engulfed me, which I did my best to hide, without success.

'It's time you were in bed,' said Mrs Partridge, looking over the top of the blameworthy glasses. 'You've had two busy days.'

It was true that I was almost asleep, but I did my best to look vivacious as I thanked her for a truly lovely evening, and departed into the rain.

Some poor baby, I thought, as I tottered home, was going to have a very odd bootee. Ah well, we all have to come to terms with life's imperfections, and one may as well begin young.

As might be expected, the minute I climbed into bed sleep eluded me, and I lay awake thinking about possible substitutes for Mrs Pringle, without success. I was going to visit her the next day, and hoped that she might have someone in mind. Otherwise, it looked as though the vicar's suggestion might have to be put into action.

After two hours or so of fruitless worrying, I heard St Patrick's clock chime, and then one solitary stroke. Very soon after this I must have fallen asleep, for I had a vivid dream in which the vicar was officiating at a marriage ceremony, clad in an improbable pale blue surplice. The bride was my importunate friend on the flight from Crete, and the groom was the monk from Toplou. Neither appeared to be interested in the ceremony, but were engrossed in a chess set which was lodged on the font.

I wonder what a psychiatrist would make of this?

The next morning I rang the hospital to enquire after my school cleaner. Mrs Pringle, I was not surprised to learn, was comfortable, and would be ready to receive visitors between two and four in the afternoon.

This was my first attempt at driving since the accident, and I was mightily relieved to find that I could do all that was necessary with my arm and foot.

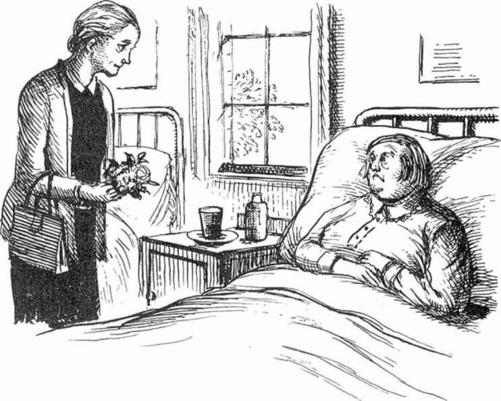

Mrs Pringle, regal among her pillows, greeted me with unaccustomed warmth, and admired the roses I had cut for her.

'A good thing I was handy for the hospital when it happened,' she told me. 'If I'd been slaving away at your place with nobody to call upon, I doubt if I'd be alive to tell the tale.'

I expressed my concern, and took the opportunity of thanking her for all the hard work she had put in at the school house, but I don't think she heard. Her mind was too full of more recent events.

'Ready to burst!' she told me with relish. 'Ready to burst! A mercy I didn't have to be jolted all the way to the County. I'd never have lasted out.'

She looked around her. Patients in neighbouring beds had fallen silent and were presumably listening to the saga. Mrs Pringle lowered her voice to a conspiratorial whisper.

'I'll tell you all about it when I'm back home,' she promised. 'There's some things you don't like to mention in mixed company.'

'Quite, quite,' I said briskly, thanking my stars for the postponement. It seemed a good opportunity to ask when she might be back in Fairacre.

'They don't tell you nothing here,' she grumbled. 'But I heard one of the nurses say something about next week, if all goes well. It don't look as though I'll be fit for school work for a bit. I've been thinking about it, and you know our Minnie's expecting again?'

I said I had heard.

'How she does it, I don't know,' sighed Mrs Pringle. I assumed that this was a rhetorical question, and forbore to respond.

'To tell you the truth, Miss Read, I've lost count now, what with his first family, and hers out of wedlock, and then these others. Then of course his eldest two are married and having families of their own. When I visit there – which isn't often I'm glad to say – there are babies all over the place, and I'm hard put to it to say whose are whose. Sometimes I wonder if Minnie knows herself.'

'No other ideas, I suppose?'

'There's Pringle's young brother, if you're really driven to it. He's quite handy at housework, but of course he'd have to come out from Caxley on the bus, and he's a bit simple. Nothing violent, I don't mean, but you'd have to watch your handbag and the dinner money.'

'It would be better to get someone in the village,' I said hastily, 'if we can find one.'

'There's no one,' said Mrs Pringle flatly, 'and we both knows it. How many wants housework these days? And specially school cleaning! Thankless job, that is, everlasting cleaning up after dozens of muddy boots. I sometimes think I must be soft in the head to keep the job on.'

Mrs Pringle's face was assuming its usual look of disgruntled self-pity, and I felt it was time to go.

'You're a marvel,' I told her, 'and keep the school beautifully. You deserve a good rest. We'll find someone, you'll see, and if the worst comes to the worst we shall have to do as the vicar suggested.'

'What's that?' asked Mrs Pringle suspiciously, on guard at once.

'Do it ourselves.'

'God help us!' cried Mrs Pringle, rolling her eyes heavenwards.

I made my farewells rapidly, before she had a total relapse.

Mr Willet turned up in the evening to cut the grass.

'I meant to have it all ship-shape for you when you got back,' he apologised, 'but what with the rain, and choir practice, and giving the Hales a hand with their outside painting when the rain let up – well, I never got round to it.'

I assured him that all was forgiven.

'That chap Hale,' he went on, 'got degrees and that, and a real nice bloke for a schoolmaster, but to see him with a paint brush is enough to make your hair curl! Paint all down the handle, paint all down his arm, drippin' off of his elbow – I tell you, he gets more on hisself than the woodwork! You could do out the Village Hall with what he wastes.'

He paused for breath.

'And how's the old girl?' he enquired, when he had recovered it. 'Still laughing fit to split?'

I said she seemed pretty bobbish, and told him about the dearth of supplementary school cleaners.

Mr Willet grew thoughtful.

'One thing, she did the place all through before she was took bad. I reckons we can keep it up together till she's fit again. After all, we shouldn't need to light them ruddy stoves she sets such store by. They're the main trouble. Won't hurt some of the bigger kids to lend a hand.'

'That's what the vicar said.'

'Ah!' nodded Mr Willet, setting off to fetch the lawn mower, 'and he said right too! Our Mr Partridge ain't such a fool as he looks.'

A minute later he wheeled out the mower. Above the clatter I heard him in full voice.

He was singing:

God moves in a mysterious way,

His wonders to perform.

15 Term Begins

A

S

always, the last week of the school holidays flew by with disconcerting speed. I had time to put the garden to rights, and to do a little shopping, but a great many other things, mainly school affairs, were shelved.

Nevertheless, I found time to call on Mrs Pringle, now at home and convalescent, and discovered, as we had all thought, that it would be two or three weeks before the doctor would allow her to resume work.

There was simply no one to be found who could take on her job, even temporarily. A fine look-out, I told myself, for the future, when Mrs Pringle finally retired. She obviously greeted my do-it-yourself plans with mixed feelings.

'It's a relief not to have our Minnie messing about with things,' she announced. 'Or anyone else, for that matter. I likes to know where to lay my hands on a piece of soap or a new dish-clorth, and where to hide the matches out of Bob Willet's way. I don't say he thieves. I'm not one to speak ill of anybody, but he sort of

borrers

them to light that filthy pipe of his, and pockets 'em absentminded. It's better there's no stranger trying to run the place.'

'I'm glad you like the idea,' I said. I was soon put straight.

'I

don't

like the idea!' boomed Mrs Pringle fortissimo. She spoke with such vehemence that I trembled for the safety of her operation scar.

'But what can I do?' she continued. 'Helpless, that's what I am, and I must just stand aside and watch them stoves rust, and the floor turn black, and the windows fur over with dust, while you and Bob Willet and the children turns a blind eye to it all.'

I said, humbly, that we would do our best, and that Mrs Willet had offered to oversee the washing-up at midday.

Mrs Pringle looked slightly mollified.

'Yes, well, that's something, I suppose. A drop in the ocean really, but at least Alice Willet knows what's what, and rinses out the tea clorths proper. Tell her I always hangs 'em on that little line by the elder bush to give 'em a bit of a blow, and then they finishes off draped over the copper.'

I promised to do so, and made a hasty departure.

'And tell Bob Willet not to lay a finger on them stoves,' she called after me. 'There's no need to light them for weeks yet.'

I let her have the last word.

Certainly, there was no need for the stoves on the first day of term. As so often happens, it dawned soft and warm, the morning sky as pearly as a pigeon's wing, and the children appeared in their summer clothes.

They all seemed to be in excellent spirits as I passed through the throng from my house to the school, and as far as I could see, attendance would not be appreciably lower, despite the measles epidemic.

A few were disporting themselves on the pile of coke, as usual, and came down reluctantly when so ordered. Unseasonably, a number of the girls were skipping together in the remains of someone's clothes line.

They were chanting:

'

Salt, mustard, vinegar',

And then, with an excited squeal: '

Pepper?

At which, the line twirled frenziedly, and some of the skippers were vanquished.

Three mothers waited with new children by the door, and I ushered them all in to enter the children for school.

Two I knew well, for both had sisters at the school, but the third was a stranger, a well-dressed dark-eyed boy of about nine.

'We're living at the cottage opposite Miss Waters,' his mother told me. 'My husband is at the atomic energy station.'

I remembered Mrs Johnson, who had lived there before, and prayed that the present tenant would not be such a confounded nuisance. She certainly seemed a pleasant person, and it looked as though Derek would be an intelligent addition to my class.

'Show Derek where to put his things, and look after him,' I said to Ernest, who was hovering near the door, anxious not to miss anything.

His mother made her farewells to the child briskly, smiled at us all and departed – truly an exemplary mother, I thought, and the boy went willingly enough with Ernest.

The other two would be entering the infants' class, and their mothers were rather more explicit in their farewells.

'Now, don't forget to eat up all your dinner, and ask the teacher if you wants the lavatory, and play with Susie at play time, and keep off of that coke, and use your hanky for lord's sake, child, and I'll see you at home time.'

Thus adjured, the children were taken into the infants' room, and I went out to call in the rest of my flock.

By age-old custom, the children are allowed to choose the hymn on the first morning of term. Weaning Patrick from 'Now the day is over', at nine in the morning, and Linda Moffat from 'We plough the fields and scatter', as being a trifle premature, we settled for 'Eternal Father, strong to save', for although we are about as far inland at Fairacre, as one can get in this island, we have a keen admiration for all sea-farers, and in any case, this majestic hymn is one of our favourites.

The new child, Derek, was standing near the piano and sang well, having a pure treble which might perhaps earn him a place at a choir school one day, I thought.

After prayers, we settled to the business of the day. Only five children were absent from my class, three with measles, one with ear-ache, and Eileen Burton for a variety of reasons supplied by her vociferous class-mates.

'Gone up her gran's,' said Patrick.

'No, she never then,' protested John. 'She's gone to Caxley with her mum about something on her foot.'