Read 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series) Online

Authors: Gary Provost

100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series) (6 page)

BOOK: 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series)

10.65Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

A transition in writing is a word or group of words that moves the reader from one place to another. The “place” might be the location of a scene, a spot in time, or an area of discussion. The transition should be quick, smooth, quiet, reliable, and logical. And it should bring to itself a minimum of attention.

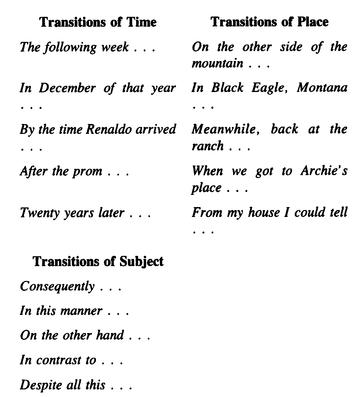

Transitions are important because they represent passage through a “danger zone” where you risk losing your reader. You use a transition to show the reader the connection between what he has just read and what he is about to read by implying the relationship between those two bodies of information. Here are some common transitional phrases:

100 WAYS TO IMPROVE YOUR WRITING

One other type of common transition occurs without words. It is the use of spaces, such as skipping lines, starting new chapters, etc.

Writers often write long-winded and unnecessary transitions because they are afraid that the short phrase hasn’t said enough. In the example below, you can see how the writer slows down the story by trying to

explain

how Sam got to the church when all he needs to do is

acknowledge

that Sam got from his apartment to a church:

explain

how Sam got to the church when all he needs to do is

acknowledge

that Sam got from his apartment to a church:

Sam moved slowly down the stairs of the apartment building. He walked across the street and climbed into

his

car. He turned the ignition key and put the car in gear. Then he pulled out into Maple Street traffic. When he reached Wilder Avenue, he took a left and drove for three blocks. At Warren Street he waited for a red light that seemed to take forever. Finally he got onto Carver. He could see the Bethany Church

up

ahead.

A better transitional sentence appears below:

Sam drove to the church.

Unless something important happened to Sam while driving his car over to the church, don’t describe the drive. A transition is simply a bridge and should be used to carry readers as quickly as possible from one place to the next.

A bridge word is a word that is used in one paragraph and then repeated in the following transition. It shows you how the writer got from one thought to another, thus supplying you with a smooth bridge between thoughts.

We use bridge words all the time to make conversations smooth. If your friend says, “Let’s pick apples Saturday. My brother Larry lives in California,” you will feel slightly jarred. You are distracted and will want to ask, “Why are you suddenly talking about your brother?” On the other hand, if your friend says, “Let’s pick apples Saturday. My brother Larry and I used to pick apples all the time. He lives in California,” the word “apples” provides you with a bridge across your friend’s thoughts, and you go along easily.

Similarly, in your writing you can convince the reader of a logical connection between subjects by using good bridge words.

In the March 1982 issue of

Esquire,

Frank Rose wrote an article called “Walking on Water,” an update on the California surfing scene. Here’s how he used the bridge word “sponsor” to make a logical transition into a discussion of media.

Esquire,

Frank Rose wrote an article called “Walking on Water,” an update on the California surfing scene. Here’s how he used the bridge word “sponsor” to make a logical transition into a discussion of media.

Unfortunately, like the good surfing spots, most potenttial sponsors have already been taken.The scramble for sponsors makes surfers especially media conscious.

Wordiness has two meanings for the writer. You are wordy when you are redundant, such as when you write, “Last May during the spring,” or “little kittens,” or “very unique.”

Wordiness for the writer also means using long words when there are good short ones available, using uncommon words when familiar ones are handy, using words that look like the work of a Scrabble champion, not a writer.

The following example of wordiness, which I’ve taken from a letter that appeared in Dr. Adele M. Scheele’s “At Work” column, which appears in newspapers all over the country, shows how dull a writer becomes when he or she tries to impress a reader with “intellectual” language.

In preparing a list of professional people whose opinion I respect, you are one of the first that comes to mind.It is my objective to more fully utilize my management expertise than has heretofore been the case....

The letter contains many of the writing mistakes we will discuss in this book, but its greatest fault is wordiness.

The overall tone of the letter is apologetic, meek, uncertain. The writer is babbling. She’s trying to find words that are safe because they are vague and they sound very professional to her. By trying to impress the reader with her vocabulary, she is composing a letter that is almost incomprehensible.

Instead of discussing herself, she discusses her “objective,” which is “to more fully utilize” her “management expertise.” She would have made herself clearer with simple words like “goal,” “use,” and “skills.” Instead of writing about her job, she writes about being confined “to the area of small business and self-employment in the apartment management field,” which doesn’t tell the reader what she’s been doing for a living, only what area she’s been doing it in.

Here is a version of that letter that is clear, direct, and simple. It would get a warm reception in any office because the reader doesn’t have to struggle to understand it.

I’ve made a list of professional people whose opinion I respect, and your name is at the top of the list.I want to use my management skills more fully. But since I’ve been running a small apartment management agency for the last six years, I’m a little bit out of touch with the job market. I’d like your guidance and advice so that I can evaluate the market for my skills....

Be a literary pack rat. Brighten up your story with a metaphor you read in the Sunday paper. Make a point with an anecdote you heard at the barber shop. Let a character tell a joke you heard in a bar. But steal small, not big, and don’t steal from just one source. Someone once said that if you steal from one writer, it’s called plagiarism, but if you steal from several, it’s called research. So steal from everybody, but steal only a sentence or a phrase at a time. If you use much more than that, you must get permission and then give credit. Here are two example of acceptable, honorable ways to steal.

Whenever people ask me what I did for a living before I became a writer, I reply, “I did all those crummy jobs that would someday look so glamorous on the back of a book jacket.” It’s a cute line, one of many I use often in order to keep myself constantly surrounded by an aura of cleverness. But I didn’t invent the line. I read it twenty years ago in a

TV Guide

article by Merle Miller, and I’ve used it ever since, rarely giving Miller credit for the line.

TV Guide

article by Merle Miller, and I’ve used it ever since, rarely giving Miller credit for the line.

The previous paragraph shows two examples of acceptable literary theft. The first is Miller’s line, which the paragraph is about. The other is the paragraph itself. It’s the opening paragraph for an article I wrote in

Writer’s Digest

(April 1983) called “Do Editor’s Steal?” I stole it from myself.

Writer’s Digest

(April 1983) called “Do Editor’s Steal?” I stole it from myself.

A novel ends when your hero has solved his problem.

An opinion piece ends when your opinion has been expressed.

An instructional memo ends when the reader has been instructed.

When you have done what you came to do, stop. Do not linger at the door saying good-bye sixteen times.

How do you know when you have finished? Look at the last sentence and ask yourself, “What does the reader lose if I cross it out?” If the answer is “nothing” or “I don’t know,” then cross it out. Do the same thing with the next to last sentence, and so forth. When you get to the sentence that you must have, read it out loud. Is it a good closing sentence? Does it sound final? Is it pleasant to the ear? Does it leave the reader in the mood you intended? If so, you are done. If not, rewrite it so that it does. Then stop writing.

CHAPTER FIVE

Ten Ways to Develop Style

1. Think About Style

2. Listen to What You Write

3. Mimic Spoken Language

4. Vary Sentence Length

5. Vary Sentence Construction

6. Write Complete Sentences

7. Show, Don’t Tell

8. Keep Related Words Together

9. Use Parallel Construction

10. Don’t Force a Personal Style

In any discussion of writing, the word style means the way in which an idea is expressed, not the idea itself. Style is form, not content. A reader usually picks up a story because of content but too often puts it down because of style.

There is no subject that cannot be made fascinating by a well-informed and competent writer. And there is no subject that cannot be quickly turned into a literary sleeping pill by an incompetent writer.

You probably would not buy Ray Bradbury’s book

Dandelion Wine

(Doubleday) if while browsing in the bookstore you turned to the version on the left (A). Contrast it with the version on the right (B), Bradbury’s actual opening paragraph. You will see that while both paragraphs contain the same information, the version on the right has style, and that makes all the difference.

Dandelion Wine

(Doubleday) if while browsing in the bookstore you turned to the version on the left (A). Contrast it with the version on the right (B), Bradbury’s actual opening paragraph. You will see that while both paragraphs contain the same information, the version on the right has style, and that makes all the difference.

Writing is not a visual art any more than composing music is a visual art.

To write is to create music. The words you write make sounds, and when those sounds are in harmony, the writing will work.

So think of your writing as music. Your story might sound like the

Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2,

or it might sound like “Satisfaction.” You decide. But give it unity. It should not sound like a musical battle between the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra and the Rolling Stones.

Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2,

or it might sound like “Satisfaction.” You decide. But give it unity. It should not sound like a musical battle between the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra and the Rolling Stones.

BOOK: 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series)

10.65Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

Eden River by Gerald Bullet

The Gentleman's Quest by Deborah Simmons

Shutout by Brendan Halpin

Tears on My Pillow by Elle Welch

Lover Be Mine: A Legendary Lovers Novel by Nicole Jordan

Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Friedrich Nietzsche, R. J. Hollingdale

Tombs of Endearments by Casey Daniels

Alice + Freda Forever: A Murder in Memphis by Alexis Coe

Home Before Midnight by Virginia Kantra

Brought to Book by Anthea Fraser