100 Mistakes That Changed History (10 page)

The long-term effect on Rome of three centuries of gradual, and occasionally not so gradual, inflation was that the empire could afford to support fewer soldiers who were less well trained. It meant that governors had to press their provinces even harder to produce ever-increasing demands for more of ever-less-valuable coins to fill their treasury. The collapses of the Western Roman empire and, a thousand years later, of the Eastern or Byzantine Roman empire were not caused directly by debased coinage, but the practice certainly contributed.

It would be nice to think that knowing all of this might mean that modern governments would not make the same mistakes. Here is some food for thought: Seventy years ago the U.S. dollar was first devalued when the Federal Reserve Bank decided to raise the cost of an ounce of gold from $20.67 to $35 per ounce. Then thirty-five years ago, the value of gold or silver was totally detached from the U.S. dollar. That was called “going off the gold,” and later the United States went off the silver standard. It was then that the bills marked as silver certificates were withdrawn from circulation. That was because technically they could be turned in at a Federal Reserve Bank for silver coins or bars. Since then, nothing has actually supported the U.S. dollar, or most other currencies, beyond the faith and promise of each government.

Just like the Roman denarius, the gradual debasing of the value of the U.S. dollar has continued without slowing. With inflation and the growing price of gold, the dollar can buy only 10 percent as much gold as it could have in 1971. That means in terms of hard exchange, the United States has debased its currency 90 percent in the last forty years. With the deficit increasing, the spiral of inflation threatens. It seems we may have learned the wrong lesson from Nero.

17

OVERCONFIDENCE

Destroyed by a Victory

70

W

hat have the Romans ever done for us? The Jews of the first century CE asked themselves that very question. Despite the obvious benefits so aptly pointed out in the opening scenes of Monty Python’s

The Life of Brian

, the Jews were not willing to give up all they held sacred for the sake of progress and profit. All the roads, running water, education, and medical attention in the world could not take the place of their religion. But for a time, it seemed that even a 3,000-year-old religion might not be able to withstand the might of the Roman empire.

Judea during the time of the early Roman empire was a volatile place. In addition to being inhabited by a people dead set on removing the Roman occupants, it was also filled with opposing factions within the Jewish community. One of these factions in particular used radical and violent means to try to push out the occupying forces. These Zealots grew tired of the religious leaders like the Pharisees and the Sadducees playing puppet to the Roman rulers. They also resented the corrupt reigns of incompetent political hacks who were the procurators that Rome had chosen to rule over Judea. Tensions came to a head around 66 CE, when the procurator, Gessius Florus, took seventeen talents of gold from the Temple treasury. That was a massive amount of wealth. Public outcry from both within the walls of Jerusalem and outside spread like wildfire. Florus answered this outcry by allowing his soldiers to pillage part of the city. In response, the city’s masses rose up against their Roman leaders and drove them out of Judea. Gessius Florus fled to the protection of another Roman garrison on the coast in Caesarea.

The people of Judea had more to contend with than corrupt government officials. Herod Agrippa the younger, who was king of Judea, had the right to nominate the high priest in Jerusalem. The Herod dynasty is sometimes a confusing one to follow, as they weren’t very innovative in naming their heirs. So, just to clear things up, this particular Herod was the nephew of Herod of Chalcis, the one mentioned in the Bible in Acts 25 and 30. Although he claimed to live by the laws of the Jews, Herod Agrippa lived with his uncle’s widow, and he spent most of his time in Rome, relishing the pagan lifestyle within the capital city.

The Zealots despised Agrippa and believed the only way to counter his oppressive regime was to start an open revolt. The Zealots demanded three things. All sacrifices to appease the emperor had to stop because they were in direct conflict with God’s law, the sanctity of the temple had to be preserved, and—most important—Judea had to have its independence. These were the only acceptable terms, and to show they were serious, the Zealots took control of the Temple in Jerusalem, while the less fanatical Jews held the rest of the city. The rebels immediately refused and forbade others to make the sacrifices required by Rome. Agrippa attempted to put the revolt down with the forces he had on hand. The Zealots led a Jewish army that first defeated Agrippa’s force of 3,000 horsemen and then later took the fortress of Masada.

Rome could not let any revolt go unpunished lest other provinces follow suit. They sent in the governor of Syria, Cestius Gallus. He tried and failed to quell the rebellion. When Gallus saw how heavily defended Jerusalem was, he hurried back to Antioch. On the way, rebel forces ambushed the unsuspecting governor and his escort. The last part of Gallus’ return to his capital was more in the form of a panicky rout.

With each Roman defeat, the rebels grew in strength and number. The Zealots, under command of John of Gischala, soon controlled most of Jerusalem. Josephus commanded the forces of Galilee. This is the same Josephus who would later write

Bellum Judaicum

(The Jewish War), giving us our main source of information about the revolt. Josephus gathered and trained troops, fortified cities, and set up an administrative body in Galilee, which was able to operate separately from Jerusalem.

The previous failure of Agrippa and then Cestius Gallus embarrassed Rome, so Flavius Vespasian was sent in to squash the rebellion once and for all. Vespasian was an experienced field commander who had been ousted from Rome for falling asleep during one of Nero’s infamous poetry readings. Apparently the general’s lack of couth in court did not carry over into his military career. He massed troops in Antioch while his son, Titus, brought in more troops from Alexandria. The two forces met and merged on the way to Judea in Ptolemais. The news of the approach of a large force of Romans reached Josephus, and he fled to the fortified city of Jotapata with his followers. The unprotected land outside of the cities fell into Roman hands without a single blow being dealt.

Vespasian focused his attention on Jotapata. The siege lasted forty-seven days. Josephus, along with forty of his men, took refuge in a cave. When their position was revealed to the Romans, Josephus decided to surrender; however, his companions did not allow it. So, Josephus had another idea. Every third man would kill his closest neighbor. When the last two men were left standing, they would draw lots to decide which man would kill the other. The last man would kill himself. This meant that only one man would break Jewish law by committing suicide. Of course, Josephus was one of the last of two men left alive. He stated in his writing that it was God’s will, but it could have simply been the result of someone who could perform simple mathematics. Josephus was taken prisoner but was later released. He lived out the rest of his life in Rome.

After taking the city of Jotapata, Titus also captured the cities of Tiberius, Taricheae, Gamala, and the Zealot base of Gischala. John of Gischala fled, and by 67 CE all of Galilee was back in the hands of the Romans. Most of Judea was also now under Roman control, leaving the holy city of Jerusalem as the final key to crushing the rebellion. But Jerusalem would not be an easy nut to crack. The fall of Galilee gave the Zealots a stronger position within the Jewish community. They assumed control of all of the city as well as the Temple. That wasn’t the only obstacle the Roman general faced. Troubles in Rome and infighting among the would-be emperors meant Vespasian would delay attacking Jerusalem for the better part of a year. Only after he had secured his place in the Roman hierarchy was he free to deal with Jerusalem.

Vespasian had to stay in Rome, so he sent his son, Titus, to retake Jerusalem and so finish what he had started. In April 70, Titus began his direct assault on Jerusalem. He stunned the Zealots by breaking through the first wall in a mere fifteen days and the second after only eight days. The third wall was quite another matter. Fifteen feet of stone separated the Roman troops from the inhabitants on the other side. Titus built massive siege towers, seventy-five feet tall, in an attempt to send his men over the top. Each tower could carry dozens of troops. The Jews answered this new threat by tunneling under the walls of the city to attack the troops inside the great towers.

They managed to cripple or destroy them all. So Titus came up with his most ruthless plan. Taking a note from Julius Caesar, he had a 4.5-mile-long wall built completely around the city. If the Jews wouldn’t surrender, he would starve them into submission. Just like at Alesia a century earlier, the Roman wall meant no supplies could reach the inhabitants within. All Titus had to do was to wait.

Then an unexpected disaster happened. The tunnel that the Jews built to try to infiltrate the siege towers collapsed. In doing so, it undermined a section of the third wall. Several meters of wall collapsed into rubble. The city was now vulnerable. Roman legionnaires stormed through the city, taking out years of frustration on the inhabitants. In the end, the Temple was destroyed and hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed. The rest were sold into slavery.

Some Jews saw this as divine punishment for those who had practiced the Roman ways. Others became even more bitter. With its main population center gone, the Jewish state became a province. Whatever the case, the destruction of the Temple of Solomon devastated the Jewish community. The rebellion that sought to empower the Jewish people instead resulted in their near destruction. They fought for their beliefs and the things they felt were theirs by right as God’s people. They wished to honor their God by refusing to make sacrifices to other gods, they wanted independence, and, most of all, they wanted to preserve the most sacred of God’s holy places, the Temple in Jerusalem. Instead, thousands were enslaved, many more were killed, and the Temple was destroyed. The heart of the Jewish people was no more. A once-strong and -vigorous people were broken and scattered. Their history changed forever because the Jewish people thought that a little bit of military success meant they could take on, most literally, the rest of the known world.

And what happened to all the gold and other artifacts that were stolen from the Temple? Vespasian used it to finance one of Rome’s most powerful symbols, the Coliseum.

18

TAKING THE EASY WAY

The Great Divide

324

W

hen the Roman emperor Diocletian decided to divide his realm into an eastern empire and a western empire, he did so in order that his forty-four provinces might be more easily governed. He obviously had never read anything on Roman history; otherwise he would have known that every time the empire had been divided to make it more manageable, it resulted only in civil war or invasion. But it is unlikely that Diocletian knew his history, because he was illiterate. The requirements for being emperor had vastly deteriorated since the time of Marcus Aurelius. Diocletian proved his ability as a military commander, but his inability to learn from the errors of his predecessors would cost his citizens greatly, eventually lead to civil war, and hasten the collapse of Roman rule in the western half of the empire.

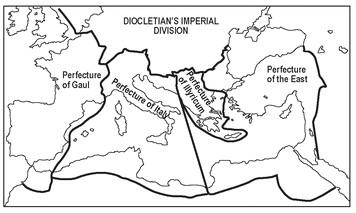

Diocletian had grown anxious about the growing number of barbarian invasions in Gaul. He had already created a mobile army to deal with the situation, but he decided that the best way to handle it would be to have a stronger power base in the west. He appointed his close friend Maximian as his co-emperor to rule from Gaul while Diocletian would rule from Nicomedia in Asia Minor. In doing this, he set up a structure that was supposed to ensure peaceful succession to each office. The two emperors would be called Augustus, and they were to pick a successor who was not a son, no matter how competent the son might be. Diocletian then chose two co-regents, who would be called Caesar. Galarius became the Caesar in the east and heir to Diocletian, while Constantius ruled with Maximian as the Caesar in the west. With separate leaders, separate armies, and even separate tax collectors, the Roman empire became in effect two empires.

Emperor Diocletian’s plan to partition the Roman empire

There was still the risk that family ties would interfere with his plans to ensure that the Caesar would become the Augustus. To keep the family ambitions of each man in the tetrarchy at bay, Diocletian “requested” that their sons live in his court. One of these sons was Constantine, the son of Constantius. Although the sons were virtually hostages, Diocletian treated them well. Despite being illiterate, he gave the boys the best education and even made sure they learned Greek. Constantine eventually became one of Diocletian’s most trusted soldiers, but the Augustus grew uneasy. The emperor had issued the Great Persecution against the Christians and, although Constantine himself did not fall into the sect, his mother did. As one of the emperor’s top men, he had witnessed many atrocities under the new edict. When the aging emperor fell ill, he failed to include Constantine in the exchange of power. Constantine realized for the first time what his position had been. He was a mere hostage and was also expendable.