03.She.Wanted.It.All.2005

Read 03.She.Wanted.It.All.2005 Online

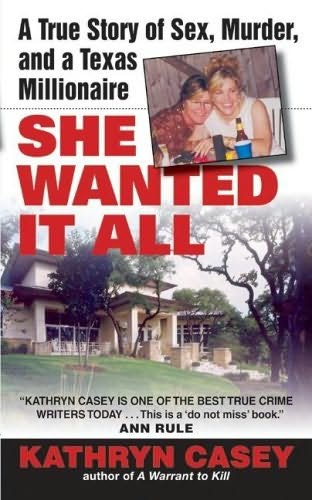

Authors: Kathryn Casey

A True Story of Sex, Murder, and a Texas Millionaire

For Ann Rule and Carlton Stowers,

my favorite true crime writers,

with gratitude for their inspiration, guidance,

and friendship

Cover

Title Page

W

est of Austin, Texas, the earth surges upward

from the coastal plain to form steep hills, and Glen Rose limestone tears jagged edges through a lush, deep green landscape. One hundred million years ago, during the Cretaceous Period when dinosaurs roamed, this part of Texas lay at the banks of a great shallow sea. When it retreated, a fierce wave wrenched the plains from the hills, birthing the Balcones, a fault line that remains hidden deep within the earth.

The Tonkawa Indians once claimed this land as their hunting grounds, harvesting the abundant deer. Gold Rushers were among the first white settlers, Carolina mountain folk whose broken wagons convinced them to abandon dreams of California fortunes. The land too rough to farm, they raised livestock, sheep and goats, intermarried and fostered bloody feuds. Later bootleggers hid stills in the thick woods atop remote hills.

Settlement proceeded slowly in the hills, the inhospitable terrain convincing many to root instead in the valleys below.

Eventually roads and electricity came. Then, in 1953, the town incorporated. Residents paid a mere $4.50 an acre in Westlake Hills. By the 1990s, when panoramic views convinced the well-off to spend up to millions to build hillside estates, the history of the land retained little use other than cocktail-party prattle.

By then some called Westlake “Lexusland.” Others dubbed it “Austin’s Hollywood Hills.” The name fit; the landscape resembled the stony cliffs over Hollywood and housed celebrities, including movie stars Sandra Bullock and Matthew McConaughey.

Even in such imposing company, the house at 3900 Toro Canyon Road held its own. At the request of its owner, Steven Beard Jr., a founder of what became Austin’s CBS affiliate, the architect sought inspiration from the Frank Lloyd Wright masterpiece Fallingwater.

A gentle creek ran beneath the house, and plump koi swam about a man-made pond. Three flights of stairs trimmed in black-granite diamonds led to heavy leaded-glass front doors that opened to a vast living room, replete with costly antiques and the best furnishings money could buy. From there, the house fanned back toward two bedroom wings, to the left the master and to the right the children’s rooms. From nearly every room, windows overlooked a pool that glistened like black satin in the moonlight.

Just before three on the morning of October 2, 1999, all was quiet on Toro Canyon. Deer circulated peacefully through the surrounding woods, chewing on ragged tree bark and feasting on tall grasses. The only disturbances were the static buzz of insects, the rustling of squirrels, and the sporadic churning of scattered air conditioners, on a still warm fall night. In another month the leaves would turn gold and brown, but on this night lush green foliage muffled the crack of a single gunshot.

Inside her bedroom, at the back of the children’s wing, eighteen-year-old Kristina Beard woke, without knowing why. A sound sleeper, she rarely stirred before morning, and as her eyes adjusted, an uneasy feeling engulfed her. All was not well. Lights flickered across the walls, white and blue. As her vision cleared, Kristina brushed her dark blond hair from her eyes and made out the form of a woman standing inside her bedroom door, staring out into the shadowy hallway.

“Mom,” said Kristina, her voice hoarse with sleep. “What’s wrong?”

First only silence, then Celeste Beard finally said, “I think it’s the police.”

Rising, Kristina joined her mother’s vigil at the door. Peering out at the silent house, the teenager saw nothing out of the ordinary, only the unrelenting lights that whipped through the darkness. Kristina’s twin sister, Jennifer, had stayed at the family lake house with friends. The only other person in the house was their adopted father, Steve Beard. An involuntary shudder ran through the teenager as she wondered who waited outside their front door and why.

“Are you sure it’s the police?” she asked.

“I think so,” Celeste said, but before Kristina realized it was happening, her mother pushed her into the hallway. “Find out what they want,” she ordered.

The frightened teenager panicked. What if the intruders weren’t police? What if someone had broken in? She darted into Jennifer’s empty bedroom and dialed 911.

“It’s EMS,” the operator said. “Your father has a medical emergency.”

“Mom, something’s wrong with Dad,” Kristina shouted, her heart racing as she ran toward the front door to unlock it for the ambulance crew, wanting them to reach her father as quickly as possible. Once there, she realized help was already

inside, as a deputy emerged from the master-bedroom wing.

“Your father’s in rough shape,” he said. “We’ve called STAR Flight to transport him to the hospital.”

“What’s wrong?” Kristina asked. Steve had been her father for four years, and he’d given her and Jennifer much. More important than wealth, he offered love and stability.

“Has he had surgery recently?” the deputy asked. “His stomach is torn wide open.”

“No,” Kristina said as her mother ran into the room.

Moments earlier, Celeste had been dead calm. Now she shrieked, “What’s wrong with my husband? What’s wrong?”

The deputy did a double take. Kristina was used to his reaction. At seventy-four, Steve was nearly old enough to be her mother’s grandfather. Strangers often looked twice at the couple. “We’re helicoptering him to Brackenridge Hospital,” he said. “You’ll be taken there, too, in a squad car.”

Not waiting for the conversation to ebb, Kristina hurried to the master bedroom to see her father. Hours earlier, when she’d looked in on him before bed, he slept peacefully. Now the sight of him made her feel ill, as EMS workers struggled to bind gaping wounds in his corpulent abdomen. His intestines spilled out onto the blood-splattered sheets. Kristina couldn’t get close but she shouted, “Dad, they’re going to take you to the hospital. You’re going to be all right. We all love you. I love you.”

Pale and weak, her father nodded.

“Is your mother all right?” he asked.

“Yes, she’s fine,” Kristina said, holding back tears. “Don’t worry. Just get better.”

In great pain, he smiled and nodded again, obviously relieved.

The longer the medics worked on her father, the more

Kristina worried. Even after the helicopter hovered over the house and drifted down to the road, they feared moving him. The wait felt like hours as she circulated between her sobbing mother and her critically injured father. On her third trip out of the master bedroom, she heard something that stunned her and she spun back into the room.

“I’ve found a shotgun shell,” a deputy had said. “He’s been shot.”

“What?” Kristina shouted.

Later the EMS workers and deputies would talk about Kristina, how she, of the two women, remained calm, comforting both her parents as the horror of what had happened became apparent. In the darkness, someone had entered their home, raised a shotgun, aimed and fired directly into her father’s ample belly. Then the intruder fled, leaving him for dead. Only sheer will kept him alive long enough to call for help.

The medical emergency now a potential murder investigation, Kristina and Celeste were surrounded as squads of police cars arrived. Throughout the chaos, the daughter comforted the mother, caring for her as if she were the parent. After the helicopter with Steve inside finally ascended into the darkness, an officer put the two women in the back of a squad car and sped down the hillside and onto the highway that led into the brightly lit streets of Austin.

By the time they arrived at the emergency room, Steve Beard had been wheeled on a gurney into surgery. His prospects weren’t good. “We don’t think he’ll survive the night,” a doctor told them.

Celeste sobbed as Kristina held her tight.

Minutes later in the hospital’s austere family waiting room, Kristina realized that for the first time since she’d awoken to flashing lights and a deep sense of foreboding,

she was alone with her mother. Suddenly, Celeste stopped crying. Her blue eyes narrowed as she focused intently on her young daughter.

“Kristina, the police are going to ask who could have done this,” she said, her voice grave. “No matter what, don’t mention Tracey’s name.”

1

O

nly months later would Kristina allow herself to

consider why Celeste ordered her not to mention the name of Tracey Tarlton to the police, even though many times throughout that strange summer she wondered about the odd relationship between her mother and the bright, funny woman who managed a large Austin bookstore. From experience, the teenager knew not to question her mother. To do so would be judged by Celeste as a betrayal, and the consequences could be bone-chilling. Throughout her life, she’d feared yet loved her mother as only a child can love a parent, with utter devotion. Only long after Steve Beard’s cold body lay entombed in a rose-granite crypt did Kristina allow herself to wonder how much she truly knew about the woman she called “Mother.”

Even if Kristina could see into the past, Celeste might have remained a mystery. For like the woman Celeste became, the household she grew up in was filled with contradiction. On the outside, Edwin and Nancy Johnson’s brood appeared a

typical 1960s middle-class family. Only decades later would a very different picture emerge.

Edwin and Nancy were an odd couple. They met after he’d left the Air Force, in the mid-fifties. Their first encounter took place in Ohio, where she worked as a telephone operator. They struck up a conversation, and Edwin told her he’d just returned to the United States after being stationed in Japan. “He talked about how he’d met a missionary who changed his life,” says Nancy, a stern woman with hornrimmed glasses and a bouffant hairdo. “Edwin talked a lot about God. He talked about morals and ethics.”

A powerfully built man who’d been a mechanic in the service, Edwin bore the scars of a traumatic beginning; reared in Connecticut, he’d lost a brother to drowning. For a year and a half, Edwin’s father blamed himself for leaving his son’s stroller unattended. Finally, when Edwin was seven, his father shot himself. “When we’d go out east, he’d take us to the river where it happened,” says Cole, the oldest of the Johnson siblings. “He had a morbid fascination about it.”

The Johnsons followed the sunshine and settled in Camarillo, California, a small town straddling the 101 freeway in a valley between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. In the sixties, Camarillo offered a peaceful life, the epitome of middle-class America. At the time, the population hovered just under 20,000. If children walking home from school were caught in the rain, local police offered rides. In the summer, families drove to the nearby beaches. School sports filled the weekends, and at the local beauty parlor and post office, gossip swirled like up-dos on prom night.

Using his Air Force nickname, Edwin opened Johnny Johnson’s Vehicles of Wolfsburg, a Volkswagen repair shop, at a time when VW Beetles and buses swarmed the hip West Coast. He became a prominent businessman and joined the

local Chamber of Commerce, while he and Nancy made plans to begin a family.

Six years into their marriage, after three miscarriages, however, the Johnsons were childless. “We decided it wasn’t going to happen, so I put out the word that we were interested in adopting,” says Nancy. In an era before legalized abortion and the pill, women needed homes for infants they couldn’t keep. “I could have had as many children as I wanted,” she says. The Johnsons adopted four babies in less than four years. The oldest, Cole, was a year when Celeste was born on February 13, 1963. Two days later, Edwin and Nancy claimed her. Nine months later, Caresse followed, then Eddy.

In years to come when her children asked about their biological mothers, Nancy offered few clues. Celeste once asked for her adoption papers, but Nancy refused. “They were mine, not hers,” she says. To Cole, Nancy said he was the offspring of a wife beater and a prostitute she’d given five dollars not to have an abortion. “Mom could be brutal,” says Cole. “She told me, ‘You’re with us because your real mother didn’t love you.’ I don’t know why she adopted us. She’d say, ‘I don’t love you, either.’”

Nancy and Edwin would later disagree about where the discord in the family originated. He described her as unstable, while she pointed an accusing finger at him. “In those years, Ed was clean-cut, every hair in place,” she says. “The shop was immaculate. But he kept me in the dark, at work, at home. He had secrets.”

Just what life was like inside the small ranch house on a cul-de-sac where the Johnson brood lived would also remain a source of dispute. Nancy would later paint a picture of suburban tranquility. “We baked cookies, went rock hunting. I took the children to Disneyland, twice,” she says. “We sang and danced.”

Yet, her children recounted few of those carefree days.

“Dad was strange and Mom was always troubled,” says Celeste’s younger sister, Caresse. “She had psychological problems. It wasn’t a happy place. Not ever.”

One of Cole’s earliest memories was terrifying. At five or six, he was in the bathtub with his brother and sisters when his mother held them underwater. “It was scary. It was like she was rinsing our hair, but she held us down too long,” he says.

Afterward, Nancy briefly went to a psychiatric hospital. “I’d suffered a breakdown,” she says. “I’d been taking diet pills, and I was under a lot of stress and had insomnia. At the time, I was thinking of a Bible passage, ‘To wash away sins.’ But I never hurt my children. I would never do that.”

After treatment, Nancy returned home to care for her brood. Edwin was gone much of the day at the shop. “We had four kids. It was a full-time commitment to keep beans on the table,” he says. When he talks of Celeste, it’s in glowing terms; she was “Daddy’s baby” and “a sweet child.”

Following their parents’ religious bent, the children attended West Valley Christian Academy. From the beginning, Celeste was a precocious child and in the program for the gifted. One year she drew greeting cards and sent them to patients in a nearby hospital. At the state fair, she and Cole entered their baked goods, cakes and cookies, and came home with ribbons. She had a wholesome, apple-cheeked look and bright, intelligent blue eyes. Everything—from her clothing to the room she shared with Caresse—was her favorite color, pink, making her the stereotypic, perfect, sweet little girl.

Cute and playful, Celeste charmed her parents. Even as a child she understood the power of a well-placed compliment. The year she turned twelve, Celeste told Edwin that a friend of hers had pointed at him and wanted to know who “that handsome guy is.”

“I told her, ‘He’s my dad,’” Celeste said. Decades later, Edwin’s voice grew emotional and proud at the memory.

In 1976, in honor of the country’s bicentennial, Edwin helped her write a speech, and Nancy made her a red, white, and blue shirt. During her performance, Eddy marveled at the way Celeste controlled the audience of parents, students, and teachers. “Celeste gave the most persuasive speeches,” he says. “She could convince people of absolutely anything.”

Yet, little Celeste Johnson had another side, one her brothers describe as frightening and calculating. “One minute she would do everything for you, bend over backward,” says Eddy. “Then she’d turn horrible, mean, positively psycho.”

When they were four small children competing for their busy parents’ attention, Cole describes Celeste as the family instigator, manipulating the others into acts that landed them in trouble. When Nancy fumed, Celeste ran to get the board used for spankings. Later, Nancy dismissed the tumult with a single sentence: “The whole family was dysfunctional.”

As the years passed, signs that the Johnsons’ second child was troubled mounted. Nancy would later describe taking Celeste to UCLA dental school for braces at the age of nine, only to have doctors remove them because she violently clenched her teeth. From an early age, she had horrific nightmares. When Nancy tried to awaken her, Celeste thrashed at her. “It was terrible,” says Nancy. “I didn’t know what was wrong.”

At first the Johnsons were able to hide the turmoil within their home; that ended in the early seventies, when a financial setback sent the family reeling. When Celeste was eleven, Edwin’s business failed. Rather than work, he went to college on the GI bill, attending Moorpark College then Pepperdine University, where he majored in speech. “Things changed,” says Eddy. “Mom went to work as a cake decorator,

and Dad put on airs, used big words, tried to impress people. Everything seemed strange.”

With Edwin not working, the problem of finances escalated. The Johnson siblings later recalled violent arguments and their father’s actions turning increasingly odd. At times he chased Cole, threatening to beat him. A neighbor saw Edwin, boiling over with anger, push a lawn mower into the front steps and scream, “There, take that.”

“Edwin just got bizarre,” says a neighbor, “while Nancy worked harder and harder to support the kids. Nobody could understand what was going on in that house.”

Without money for tuition, the children were enrolled in public schools. At home, Celeste acted out. “She was hell on wheels when she turned thirteen,” says Nancy. “I didn’t know why. I was struggling just to keep food on the table. I left early in the morning and came home late at night.”

Perhaps making the situation even more painful for Celeste than the changes in her father and the absence of both her parents was the contrast between her family and that of Nancy’s wealthy friend Louise, who went to the same church as the Johnsons. Celeste and Louise’s daughter were friends, and Louise’s parents bought Celeste expensive presents and took her on trips. “Celeste liked the money,” says Cole. “She saw what it could buy.”

The tension at the Johnson house escalated. Edwin was a different man than the one Nancy married, scruffy, unshaven, and he called himself by a biblical name, Jedediah.

On Christmas Eve 1977, Nancy ordered him from the house.

For the next three years they waged a divorce that had such venom no one escaped its poison. They fought over money, Edwin’s shop tools, and the children. “Dad was crazy,” says Cole. “But Mom was vindictive. She brainwashed the girls to hate our dad.”

“Celeste changed in junior high school,” says Caresse. “She got in trouble, and she was angry all the time. She was a different person after my mom kicked my dad out.”

By the time Celeste turned fourteen, everyone within the Johnson household agreed that she was out of control. She had fights with siblings that her youngest brother, Eddy, compares in violence to a Mike Tyson match. “We couldn’t be together. She’d beat me up, and someone in the neighborhood would call the police,” he says. “The cops were always there, making her stop.”

One day, Cole arrived home to find Celeste pounding on their mother’s back, screaming at her. “She had so much anger,” he says. “It was awful.”

Another day, Nancy woke her for school and a screaming match ensued that ended with Celeste putting her fist through a front-door window. Someone called the police, and the house was surrounded. “They took Celeste in, and the judge ordered her to do community service and go to counseling,” says Nancy. “But by then I was already taking her to psychiatrists. They couldn’t figure out what was wrong with her.”

Once, when Nancy asked Celeste why she was so angry, the teenager simply said, “I’m just trying to get your attention.”

At Camarillo High School, where the teams are known as the Scorpions, Celeste lettered freshman year on the varsity swim team and was a member of the debate team. She appeared a studious girl—always carrying a satchel of books—tall, with long legs, thick blond hair, and deep blue eyes. She had high cheekbones in a slightly elongated face, a carefree manner, and the body of a swimmer, lean and athletic, the very picture of the California girl the Beach Boys celebrated in song. She hung with other kids like herself, those from broken homes. Some remembered her big smile

and a laugh that verged on a girlish giggle. She also had a way about her that friends later struggled to explain. “It was like Celeste could see inside of you,” says one. “She sized people up, knew how to get what she wanted. She did it with teachers, even the rest of us kids.”

In many ways, Celeste was an odd mix. She never dressed overtly sexually, instead preferring modest clothes. One friend teased her, saying that she looked like she’d raided her mother’s closet. But she seemed to know without question what men were looking for. “She flirted, in a taunting way,” says a classmate. “Then she’d come across as sweet and innocent. It was an amazing combination. It drove the guys in town crazy.”

Along with her beauty, Celeste had an untamed, wild streak that some found fascinating. When she got her driver’s license, she screamed down the streets in the family’s VW Beetle. At night she teased the neighborhood boys, parading down the street in her nightgown, often with nothing underneath. Cole chased away the clique of boys who catcalled at her. “Celeste laughed, having a good old time with it,” says Eddy.

One incident resonated for Cole; in high school, he had his first sexual experience. The girl then said something that shocked him: “I’ve already done it with Celeste.”

“I always thought Celeste hated men and leaned toward being a lesbian,” he says.

Still, men were attracted to Celeste and, from all appearances, she to them.

Decades later, Craig Bratcher told his family he met Celeste in a bar, when she nuzzled against him, then kissed him. Before long they were making out. Craig, then seventeen, was two years older than Celeste. With his parents divorced the house Craig lived in with his father and brothers was a magnet for the teenagers in the neighborhood, including

Celeste. “There was something about Craig that I respected,” says a friend of Celeste’s. “He took things seriously.”

Many would say there was something special about Craig. He was muscular, with a slight paunch. Long brown hair combed to the side fell over his forehead and brushed the tops of thick eyebrows, over sad, dark eyes. He came from a family of four brothers and worked with his father for a big produce company that harvested the bounty of the neighboring valleys.

Perhaps Craig was already troubled when he met Celeste. More than one friend describes him as extraordinarily shy. “Craig had his ups and downs,” says his mom, Cherie Falke. “But he was young, just learning to get on in life, when he met Celeste. From the beginning, their relationship was a mistake.”