What Hath God Wrought (68 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

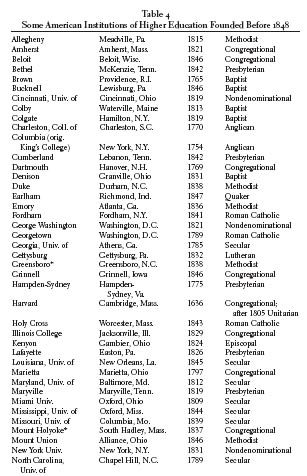

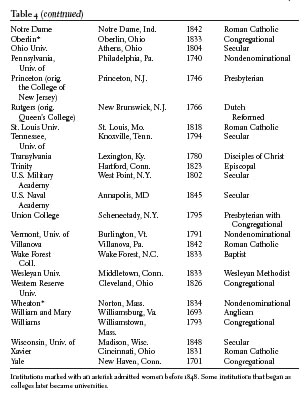

Disestablishment did not dismay New England’s Congregationalists. Looking for ways to reassert their influence, they founded educational institutions. Yankees moving west created a host of Congregationalist colleges across their band of settlement, including Western Reserve University and Oberlin College in Ohio, Illinois College, Beloit College in Wisconsin, and Grinnell College in Iowa. Some of these institutions were in effect daughter colleges of Yale, founded by Yale graduates and imitating the Yale curriculum.

39

But in the enthusiasm of the Second Great Awakening, the denominations that had never been established proved even more prolific in founding colleges than did Congregationalists and Episcopalians. By 1848, the Presbyterians had founded the most colleges (twenty-five), followed by Methodists and Baptists (with fifteen each), Congregationalists (fourteen), and Episcopalians (seven). Presbyterian Princeton had an academic empire in the South comparable to Yale’s in the North.

40

Since denominational affiliation mattered little to the college curriculum in most cases, student bodies typically included youths from the area across denominational lines. These numerous little colleges were serving the purposes of their local communities, not just their particular sects. But they existed on the margin of financial viability and frequently succumbed to the same economic downturns that claimed business and financial enterprises.

41

In 1815, thirty-three colleges existed in the United States; by 1835, sixty-eight; and by 1848, there were 113. Sixteen of these were state institutions, which by then were generally distinguishable from private religious ones. Eighty-eight were Protestant denominational colleges; the remaining nine, Roman Catholic.

42

Catholic educational initiatives in the United States were largely the work of religious orders. They included Georgetown and Fordham (both Jesuit), Notre Dame (Order of the Holy Cross), and Villanova (Augustinian). All these were founded in advance of heavy Catholic immigration; they aimed initially at proselytizing, not simply catering to an existing Catholic population. Protestants like Lyman Beecher correctly interpreted the Catholic institutions as an ideological challenge.

American higher education responded to pressure for vocational utility at the graduate level. The early national period witnessed the foundation of professional schools, starting with medicine, law, and divinity. At the undergraduate level, however, Protestant, Catholic, and public colleges all emphasized a liberal education—that is, one designed to develop the student’s intellectual powers rather than to provide vocational training. It was termed “liberal” because designed to be liberating and thus suitable for a free man (

liber

meaning “free” in Latin).

43

The Yale Report of 1828, issued by the faculty of what was then the country’s largest and most influential institution of higher learning, defended the traditional conception of a liberal education against its critics. The curriculum centered on the classics, particularly Latin. Advocates of curricular innovation succeeded in introducing modern history, modern literature, and modern foreign languages, but classics remained the core discipline, along with some mathematics and science. Colleges generally required some Latin for entrance, which in turn influenced secondary school curricula. Undergraduates had few elective subjects. Classical study inculcated intellectual discipline and provided those who pursued it, the world over, with a common frame of reference. The use of Latin marked one as educated and gave weight to one’s arguments. Physicians wrote their prescriptions in Latin; lawyers sprinkled their arguments with Latin phrases. American statesmen defended their principles of “classical republicanism” with arguments drawn from Aristotle, Publius, and Cicero. Sculptors flattered public figures by portraying them in togas. Congress met in a Roman-style Capitol.

44

A distinctive feature of antebellum American colleges was the course on moral philosophy, typically taught to seniors by the president of the college. The capstone of an undergraduate education, it treated not only the branch of philosophy we call ethical theory but also psychology and all the other social sciences, approached from a normative point of view. The dominant school of thought was that of the Scottish philosophers of “common sense,” Thomas Reid and Dugald Stewart, plus Adam Smith (whom we remember mostly for his work in economics, then a branch of moral philosophy). These philosophers were valued for their rebuttal to the atheistic skepticism of David Hume, their reconciliation of science with religion, and their insistence on the objective validity of moral principles. They sorted human nature into different “faculties” and explained the difficult, yet important, task of subordinating the instinctive and emotional faculties to the higher ones of reason and the moral sense. Moral philosophy as taught in the colleges reflected American middle-class culture’s preoccupation with character and self-discipline. This course, very similar at all public and Protestant colleges, substituted for the study of sectarian religious doctrine, which moved into the professional divinity schools and seminaries for training ministers.

45

The colonial Puritans had included educational provision for girls as well as boys in their primary schools, and in the early nineteenth-century United States, secondary education opened up to girls with little controversy. The finest girls’ secondary school, Troy Female Seminary, founded in 1821 by Emma Willard, offered college-level courses in history and science. By the middle of the century, the United States had become the first country in the world where the literacy rate of females equaled that of males. At least as startling, the first few higher educational opportunities appeared for women. Religious motivations remained important in this, illustrated by the Calvinism of Mount Holyoke College, the evangelical abolitionism of coeducational Oberlin, and the Wesleyan Methodism of Georgia Female College, all of them founded in the 1830s. No individual did more to apply the Second Great Awakening to women’s education than Catharine Beecher, eldest daughter of the evangelist Lyman Beecher.

46

The United States pioneered higher education for women, and by 1880 one-third of all American students enrolled in higher education were female, a percentage without parallel elsewhere in the world.

47

Scholars have often debated how far American history is “exceptional” by comparison with the rest of the world. No better example of American exceptionalism exists than higher education for women. Through the efforts of Christian missionaries, the American example of higher education for women has influenced many other countries.

IV

As this chapter is written in the early twenty-first century, the hypothesis that the universe reflects intelligent design has provoked a bitter debate in the United States. How very different was the intellectual world of the early nineteenth century! Then, virtually everyone believed in intelligent design. Faith in the rational design of the universe underlay the worldview of the Enlightenment, shared by Isaac Newton, John Locke, and the American Founding Fathers. Even the outspoken critics of Christianity embraced not atheism but deism, that is, belief in an impersonal, remote deity who had created the universe and designed it so perfectly that it ran along of its own accord, following natural laws without need for further divine intervention. The commonly used expression “the book of nature” referred to the universal practice of viewing nature as a revelation of God’s power and wisdom. Christians were fond of saying that they accepted two divine revelations: the Bible and the book of nature. For deists like Thomas Paine, the book of nature alone sufficed, rendering what he called the “fables” of the Bible superfluous. The desire to demonstrate the glory of God, whether deist or—more commonly—Christian, constituted one of the principal motivations for scientific activity in the early republic, along with national pride, the hope for useful applications, and, of course, the joy of science itself.

48

One such demonstration of divine purpose appeared in the widely used textbook

Natural Theology

(1805 and ten subsequent American editions by 1841), written by the English clergyman William Paley. Paley presented innumerable cases to illustrate the teleological argument for the existence of God (that is, the argument that we find apparent design in nature and can infer from this a purposeful designer). For example, Paley argued, the physiology of the human eye shows as much design as a human-made telescope.

49

Though a popularizer, Paley did not misrepresent the attitude of most scientists of his time. Natural theology, the study of the existence and attributes of God as demonstrated from the nature He created, was widely studied and Paley’s book used as its text. A synthesis of the scientific revolution with Protestant Christianity viewed nature as a law-bound system of matter in motion, yet also as a divinely constructed stage for human moral activity. The psalmist had proclaimed, “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament showeth his handiwork.” The influential Benjamin Silliman, professor of chemistry and natural history at Yale from 1802 to 1853, affirmed that science tells us “

the thoughts of God

.”

50

Silliman and other leading American scientists like Edward Hitchcock and James Dwight Dana harmonized their science not only with intelligent design but also with scripture. They insisted that neither geology nor the fossils of extinct animals contradicted the book of Genesis. They interpreted the “days” of creation as representing eons of time and pointed out that Genesis had been written for an ancient audience, with the purpose of teaching religion, and not to instruct modern people in scientific particulars. Scientists varied in the importance they attached to identifying approximate parallels between science and scripture, such as comparing geologic evidence of past inundation with Noah’s flood. The most widely held theory explaining the emergence of different species over time, that of the great French biologist Georges Cuvier, held that God had performed successive acts of special creation. When the Scotsman Robert Chambers published

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

in 1844, anticipating Darwin’s theory of evolution, he still argued that evolution was compatible with intelligent design. The scientific community rejected this theory of evolution until Charles Darwin supplied a theory of natural selection to explain how it worked. But Louis Agassiz of Harvard, the renowned discoverer of past ice ages, defended the theory of special creation even after Darwin published his

Origin of Species

in 1859. His Harvard colleague botanist Asa Gray led the American fight to accept the theory of evolution, but argued (contrary to Darwin’s own opinion) for evolution’s compatibility with intelligent design.

51

The early nineteenth century distinguished two branches of science: natural history (biology, geology, and anthropology, all then considered mainly descriptive) and natural philosophy (physics, chemistry, and astronomy, more mathematical in nature). Scientific activity in the United States emphasized natural history, the collection of information about flora, fauna, fossils, and rocks. Exploring parties like those of Lewis and Clark in 1804–6, Army Major Stephen Long across the Great Plains in 1819–23, and Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes through the Pacific in 1838–42 contributed to this knowledge. Many scientists were actually amateurs who earned their living in other ways, frequently as clergymen, physicians, or officers in the armed forces. Science figured in the standard curriculum of both secondary and higher education, and the subject enjoyed a broad base of interest in the middle class. Science, like technology, benefited from the improving literacy and numeracy of nineteenth-century Americans. Popular magazines carried articles encouraging interest in the natural history of the New World. The perceived harmony between religion and science worked to their mutual advantage with the public. As the industrial revolution reflected the ingenuity of innumerable artisans, so early modern natural history profited from the dedicated curiosity of many nonprofessional observers and collectors—women as well as men.

52