What Hath God Wrought (62 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

The Chickasaws of Mississippi tried to spare themselves some suffering by quickly accepting the inevitable and consenting to move west. Then it turned out that the administration had neglected to identify anyplace for the tribe to relocate. Eventually the Chickasaws themselves purchased a section of the Choctaw domain in Oklahoma in order to escape from the persecutions to which they were being subjected by intruders on their lands in Mississippi.

The Seminoles in Florida Territory proved the most difficult of the southeastern tribes to expel. Willing to fight for their homes, they put up a resolute resistance and benefited from a remote defensible bastion and the assistance of runaway slaves. A treaty consenting to Removal, extorted from a group of Seminoles in 1833 when they visited Oklahoma, was repudiated by the tribe but accepted as binding by the administration. In December 1835, a hundred soldiers under Major Francis Dade were annihilated by a combined force of Indians and blacks. When Jackson left office in March 1837, the federal government had undertaken a serious war effort, and the fate of the Seminole tribe was still unresolved. Before it was through, the government would spend ten times as much on subjugating the Seminoles alone as it had estimated Removal of all the tribes would cost.

15

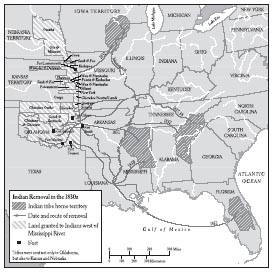

Tribes were sent not only to Oklahoma, but also to Kansas and Nebraska.

The administration’s Removal policy applied to all Indians east of the Mississippi, not only those of the Deep South. In the Northwest it led to a tragic conflict known as Black Hawk’s War. In April 1832, Black Hawk led between one and two thousand people of the Sac and Fox tribes to cross the Mississippi and return to land in northern Illinois where their right of occupancy was now disputed. Black Hawk had long advocated inter-tribal resistance to white encroachment and had sided with the British during the War of 1812; more recently he had been losing influence to his rival leader, Keokuk, an advocate of accommodation with the settlers. On this occasion, Black Hawk and his band were seeking not conflict but refuge from their traditional enemies, the Sioux; a war party would not have included women and children. Illinois governor John Reynolds nevertheless interpreted their move into his state as hostile. As soon as Black Hawk realized that he could persuade neither other tribes nor Canadian traders to support his venture into Illinois, he tried to surrender. On May 14, a delegation of Indians seeking to negotiate under a flag of truce was fired upon by state militiamen; in the battle that followed, the disorganized militia were routed.

16

Secretary of War Cass seized this opportunity. He summoned federal troops, requested more Illinois militia to support them, and rushed himself to Detroit so as to be closer to the scene. Among the men assembled for service in the brief campaign were future presidents Abraham Lincoln (whose grandfather had been killed by Indians on the Kentucky frontier), Zachary Taylor, and Jefferson Davis. Jackson pressed the local commander for action, and the hastily gathered army then drove Black Hawk’s band away, pursuing them into what is now Wisconsin, and massacring several hundred men, women, and children at Bad Axe on August 2, 1832, as they were trying to flee back across the Mississippi. Those who made it across were killed by Sioux allied with the government. Of all Black Hawk’s band, scarcely 150 survived. The administration’s seeming overreaction paid off: Peace treaties followed, depriving the Sac and Fox and Winnebago tribes of more lands. The government exhibited the prisoner Black Hawk around the country, as the imperial Romans did with captive monarchs; by his dignity and eloquence, the old warrior won the lasting admiration of the American public.

17

Only belatedly did the Jackson administration address the fact that shoving eastern tribes onto the Great Plains would require the tribes who already lived there to turn over some of their historic lands to newcomers. In 1835, the government authorized a commission chaired by Montfort Stokes of North Carolina to seek suitable agreements. Expeditions by cavalry and dragoons based at Fort Leavenworth and Fort Scott, Kansas, eventually persuaded some of the Plains tribes to sign the required treaties, though friction among the different tribes of original inhabitants and relocated easterners would remain, one more tragic aspect of Indian Removal. In 1841, a conscientious investigation of the government’s treatment of the exiles, by Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock of the Regular Army, revealed widespread corruption by white contractors.

18

Andrew Jackson mobilized the federal government behind the expropriation and expulsion of a racial minority whom he considered an impediment to national integrity and economic growth. Before the end of his two terms, about forty-six thousand Native Americans had been dispossessed and a like number slated for dispossession under his chosen successor. In return Jackson had obtained 100 million acres, much of it prime farmland, at a cost of 30 million acres in Oklahoma and Kansas plus $70 million ($1.21 billion in 2005, insofar as such equivalents can be calculated).

19

Little of the money ended up with the American Indians, but its expenditure seriously compromised Jackson’s pledges of strict republican economy. Of course, the blame for the dispossession and expulsion of the tribes must be widely shared among the white public, and even a sympathetic administration found it difficult to protect Indian rights, as John Quincy Adams’s experience proved. But Jackson’s policies encouraged white greed and made a bad situation worse. In some places where the administration did not resort to force to expel them, modest numbers of tribal Indians succeeded in remaining east of the Mississippi, including Iroquois in New York and Cherokee in North Carolina.

Nor did the fault lie simply with the inefficient and corrupt implementation of Removal, rather than with Jackson’s policy itself. The Indian Removal Bill called for renegotiating treaties and (assuming what the outcome of the negotiations would be) funding deportation. The treaty-making process was notorious for coercion and corruption, as Jackson knew from firsthand experience, and the new treaties concluded under his administration carried on these practices. Jackson’s favorite negotiator, John F. Schermerhorn, despite much contemporary criticism for his chicanery, was reappointed and rewarded by the president. Firmly believing that “Congress has full power, by law, to regulate all the concerns of the Indians,”

20

Jackson found it convenient to pretend that the states had authority to extend their laws over the tribes because he knew the states would make life intolerable for the Natives. After the white populace and their state governments had looted and defrauded the helpless minority group, Jackson (as the historian Harry Watson has put it) “struck a pose as the Indians’ rescuer,” offering deportation as their salvation.

21

During the Removal process the president personally intervened frequently, always on behalf of haste, sometimes on behalf of economy, but never on behalf of humanity, honesty, or careful planning. Army officers like General Wool and Colonel Zachary Taylor who attempted to carry out Removal as humanely as possible or to protect acknowledged Indian rights against white intruders learned to their cost that Jackson’s administration would not back them up.

22

Indian Removal reveals much more about Jacksonian politics than just its racism. In the first place it illustrates imperialism, that is, a determination to expand geographically and economically, imposing an alien will upon subject peoples and commandeering their resources. Imperialism need not be confined to cases of overseas expansion, such as the western European powers carried on in the nineteenth century; it can just as appropriately apply to expansion into geographically contiguous areas, as in the case of the United States and tsarist Russia.

Imperialism

is a more accurate and fruitful category for understanding the relations between the United States and the Native Americans than the metaphor of

paternalism

so often invoked by both historians and contemporaries (as in treaty references to the “Great White Father” and his “Indian children”). The federal government was too distant and too alien, too preoccupied with expropriation rather than nurture, for a parental role to describe the relationship, save perhaps as a sinister caricature. Paternalism might be invoked with more justice to characterize the attitude of the Christian missionaries to the Indians.

Besides eagerness for territorial expansion, Jackson’s Indian policy also demonstrates impatience with legal restraints. The cavalier attitude toward the law expressed by Jackson (who was, after all, a Tennessee lawyer and judge) was widespread among his fellow countrymen. The rule of law obtained only in places and on subjects where local majorities supported it. At times during the Georgia gold rush, for example, neither the Cherokee Nation, the state authorities, nor the federal government could enforce law and order. The restoration of legal order to the gold fields came as a result of a desire for secure property titles. Relations with the Indian tribes turned out to be one area of American law where John Marshall’s Supreme Court did not make good on its attempt to set binding precedent. When more cases involving Indian rights came before the Court after Marshall’s death, the new majority of Jackson appointees disregarded

Worcester v. Georgia

and instead restored the doctrine of

Johnson v. M’Intosh

(1824), affirming white sovereignty over aboriginal lands based on a “right of discovery.”

23

During the generations to come, state governments all over the country repeatedly asserted their supremacy over Indian reservations, state courts enforced it, and the federal government, including the judiciary, acquiesced. Even after tribes had relocated to the west of the Mississippi River, their ability to remain on their new domain was no more secure than it had been on their old. In 1831–32, the state of Missouri expelled its Shawnee residents and turned their farms and improvements over to white squatters.

24

The president’s stated goals in Indian Removal included the spread of white family farming, for “independent farmers are everywhere the basis of society, and the true friends of liberty.”

25

But Jackson’s insistence on opening up the Indian lands quickly, in advance of actual white population movement, played into the hands of speculators with access to significant capital, who engrossed the best lands. Not until his Specie Circular of 1837, issued just before he left office, did Jackson give any indication of wishing to discourage speculation in expropriated Indian lands. Of course, when small farmers got the chance, they too participated in land speculation to the extent that their resources permitted; even actual settlers commonly chose their sites with an eye to later resale.

26

Martin Van Buren correctly predicted that the issue of Indian Removal would “occupy the minds and feelings of our people” for generations to come.

27

Today Americans deplore the expropriation and expulsion of racial minorities, a practice now called “ethnic cleansing.” The state of Georgia repealed its Cherokee laws in 1979 and exonerated Worcester and Butler in 1992, calling their imprisonment “a stain on the history of criminal justice in Georgia.”

28

The federal government has set up markers along the Trail of Tears, which an American of today may observe with shame at the country’s past offenses, leavened with at least some pride at the nation’s willingness to confess them.

IV

White supremacy, resolute and explicit, constituted an essential component of what contemporaries called “the Democracy”—that is, the Democratic Party. Jackson’s administrations witnessed racial confrontation not only between whites and Native Americans but also between whites and blacks. In the case of African Americans, however, the government did not embark on an initiative of its own like Indian Removal but responded to actions by the blacks themselves and their handful of radical white supporters.

Six months after Jackson’s inauguration appeared the most incendiary political pamphlet in America since Tom Paine’s

Common Sense

. It bore a long title:

An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, But in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America

. The author, a self-educated free black man named David Walker, owned a used clothing store near the Boston waterfront. Active in the AME Church and an admirer of its Bishop Richard Allen, Walker contributed to the New York–based black newspaper

Freedom’s Journal

. Walker’s

Appeal

, published on September 28, 1829, deployed a wide range of learning marshaled in the service of moral outrage. It denounced not only the institution of slavery but also the indignities to which all black people, free as well as slave, were subjected.