What Hath God Wrought (33 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

Because of the scheduled packets, news from Europe almost always arrived in New York City first. Competition among the packets placed a greater emphasis on speed, and these sailing vessels out of Liverpool shaved the average westward crossing time from fifty days in 1816 to forty-two days a decade later. Beginning in 1821, arriving ships would send semaphore signals of the most important messages to watching telescopes on shore, saving precious hours in transmitting information. During the 1830s, two New York commercial papers, the

Journal of Commerce

and the

Courier and Herald

, starting sending schooners fifty to a hundred miles out to sea to meet incoming ships and then race back to port with their news, trying to scoop each other.

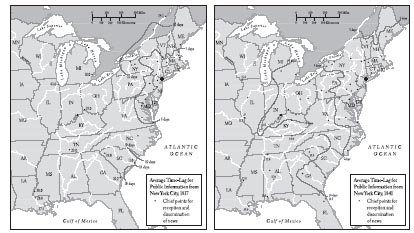

From New York City, information dispersed around the country and appeared in local newspapers. In 1817, news could get from New York to Philadelphia in just over a day, traveling as far as New Brunswick, New Jersey, by steamer. To Boston from New York took more than two days, with the aid of steamboats in Long Island Sound. To Richmond the news took five days; to Charleston, ten.

55

These travel times represented a great improvement over the pre-steamboat 1790s, when Boston and Richmond had each been ten days away from New York, but they would continue to improve during the coming generation. For the most important news of all, relay express riders were employed. In 1830. these riders set a record: They carried the presidential State of the Union message from Washington to New York in fifteen and a half hours.

56

Communications profoundly affected American business. For merchants eagerly awaiting word of crop prices and security fluctuations in European cities, the advantage of being one of the first to know such information was crucial. New Yorkers benefited because so many ships came to their port first, even though Boston and Halifax, Nova Scotia, were actually closer to Europe. The extra days of delay in receiving European news handicapped merchants based in Charleston, Savannah, or New Orleans. The availability of information affected investors of all kinds, not only commodity traders. No longer did people with money to invest feel they needed to deal only with their relatives or others they knew personally. Through the New York Stock Exchange, one could buy shares in enterprises one had never seen. Capital flowed more easily to places where it was needed. Information facilitated doing business at a distance; for example, insurance companies could better assess risks. Credit rating agencies opened to facilitate borrowing and lending; the first one, the Mercantile Agency, was established by the Tappan brothers, who also created the New York

Journal of Commerce

and bankrolled much of the abolitionist movement.

57

In colonial times, Americans had needed messages from London to provide commercially relevant news. Now, they could get their news from New York and get it faster. Improved communications stimulated economic growth.

58

Among the lessons learned from the War of 1812, the military importance of communication seemed clear. Better communications would have made the Battle of New Orleans unnecessary; indeed, faster communication between Parliament and Congress might well have avoided the declaration of war in the first place. If war did have to be waged in North America, better communications would enable the high command in Washington to maintain military command and control better than it had along the Great Lakes frontier in 1812–13. Events in Florida in 1818 underscored this need. Influenced by defense considerations as well as by the economic interests of those who needed to keep abreast of the market, the federal government played a central role in the “communications revolution” which accompanied the “transportation revolution.” Together, the two revolutions would overthrow the tyranny of distance.

59

Source for both maps: Allan Pred,

Urban Growth and the Circulation of Information

(Harvard University Press, 1973).

The United States Post Office constituted the lifeblood of the communication system, and it was an agency of the federal government. The Constitution explicitly bestowed upon Congress the power “to establish post offices and post roads.” Delivering the mail was by far the largest activity of the federal government. The postal service of the 1820s employed more people than the peacetime armed forces and more than all the rest of the civilian bureaucracy put together. Indeed, the U.S. Post Office was one of the largest and most geographically far-flung organizations in the world at the time. Between 1815 and 1830, the number of post offices grew from three thousand to eight thousand, most of them located in tiny villages and managed by part-time postmasters. This increase came about in response to thousands of petitions to Congress from small communities demanding post offices. Since mail was not delivered to homes and had to be picked up at the post office, it was a matter of concern that the office not be too distant. Authorities in the United States were far more accommodating in providing post offices to rural and remote areas than their counterparts in Western Europe, where the postal systems served only communities large enough to generate a profitable revenue.

60

In 1831, the French visitor Alexis de Tocqueville called the American Post Office a “great link between minds” that penetrated into “the heart of the wilderness”; in 1832, the German political theorist Francis Lieber called it “one of the most effective elements of civilization.”

61

The expansion of the national postal system occurred under the direction of one of America’s ablest administrators, John McLean of Ohio. McLean served as postmaster general from 1823 to 1829, under both Monroe and John Quincy Adams. Like just about everybody in Monroe’s cabinet, he nursed presidential ambitions. Waiting for his chance at the big prize, he allied himself politically with John C. Calhoun and shared the young Calhoun’s nationalistic goals. While European postal services were run as a source of revenue for the government, McLean ran the U.S. Post Office as a service to the public and to national unification. He sought to turn the general post office into what one historian has described as “the administrative headquarters for a major internal improvements empire that would have built and repaired roads and bridges throughout the United States.”

62

But John McLean proved no more able to make himself a transportation czar than Albert Gallatin. Congressmen were not willing to delegate such authority, since it would have sacrificed their own power over favorite projects and “pork barrel” appropriations.

Not only did improved transportation benefit communication, but the communication system helped improve transportation. Even without a central plan, the post office pushed for improvements in transportation facilities and patronized them financially when they came. The same stagecoaches that carried passengers along the turnpikes also carried the mail, and the postmaster general constantly pressed the stages to improve their service (though, because the federal government subsidized the means of conveyance but seldom the right of way over which they traveled, passengers complained bitterly about the wretched roads). Contracts for carrying mail helped finance the early steamboats as well as nurture the stagecoach industry. Bidders for the contracts competed feverishly with each other—which did not hurt the political influence of the postmaster general. When a two-party system came to American politics, it would be predicated upon the existence of an enormous Post Office, both as a means of distributing mass electoral information such as highly partisan newspapers and as a source of patronage for the winners.

63

Newspapers, not personal letters, constituted the most important part of the mail carried by the Post Office. Printed matter made up the overwhelming bulk of the mail, and it was subsidized with low postal rates while letter-writers were charged high ones. Editors exchanged complimentary copies of their papers with each other, and the Post Office carried these free of charge; in this way the provincial press picked up stories from the metropolitan ones. The myriad of small regional newspapers relied on cheap postage to reach their out-of-town, rural subscribers. As early as 1822, the United States had more newspaper readers than any other country, regardless of population. This market was highly fragmented; no one paper had a circulation of over four thousand. New York City alone had 66 newspapers in 1810 and 161 by 1828, including

Freedom’s Journal

, the first to be published by and for African Americans.

64

The expansion of newspaper publishing resulted in part from technological innovations in printing and papermaking. Only modest improvements had been made in the printing press since the time of Gutenberg until a German named Friedrich Koenig invented a cylinder press driven by a steam engine in 1811. The first American newspaper to obtain such a press was the

New York Daily Advertiser

in 1825; it could print two thousand papers in an hour. In 1816, Thomas Gilpin discovered how to produce paper on a continuous roll instead of in separate sheets that were slower to feed into the printing press. The making of paper from rags gradually became mechanized, facilitating the production of books and magazines as well as newspapers; papermaking from wood pulp did not become practical until the 1860s. Compositors still set type by hand, picking up type one letter at a time from a case and placing it into a handheld “stick.” Until the 1830s, one man sometimes put out a newspaper all by himself, the editor setting his own type. The invention of stereotyping enabled an inexpensive metal copy to be made of set type; the copy could be retained, and if a second printing of the job seemed warranted (such as a second edition of a book), the type did not have to be laboriously reset.

65

More important than innovations in the production of printed matter, however, were the improvements in transportation that facilitated the supply of paper to presses and then the distribution of what they printed. After about 1830, these improvements had reached the point where a national market for published material existed.

About half the content of newspapers in this period consisted of advertising, invariably local. (Half of daily newspapers between 1810 and 1820 even used the term “advertiser” in their name.) The news content, however, was not predominantly local but rather state, national, and international stories. Many if not most newspapers of the 1820s were organs of a political party or faction within a party, existing not to make a profit but to propagate a point of view. Since custom inhibited candidates for office from campaigning too overtly (especially if running for the presidency), partisan newspapers supplied the need for presenting rival points of view on the issues of the day. Such papers relied on subsidies from affluent supporters and government printing contracts when their side was in power.

66

The newspapers of the early republic often printed speeches by members of Congress, a particularly valuable service since Congress itself did not publish its own debates until 1824. The papers also published periodic “circular letters” from the members to their constituencies. Newspapers played an essential role in making representative government meaningful and in fostering among the citizens a sense of American nationality beyond the face-to-face politics of neighborhoods.

67

It did not require much capital to publish one of the small papers typical of the day. Even a limited circulation made the enterprise viable, and papers often catered to a specific audience. One kind of newspaper specialized in commercial information, especially commodity and security prices; a business and professional readership avidly devoured such periodicals, while many planters and farmers took an interest in their subject matter too. The party-political press and the newspapers published for profit competed with each other for advertisers and readers, and over the next generation the distinction between them blurred. In 1833, the

New York Sun

reached out for a truly mass audience by charging only a penny a copy and selling individual copies on the street instead of by subscription only; soon it had many imitators. The

New Orleans Picayune

, founded in 1837, took its name from the little coin that defined its price. The drop in prices quickly produced a dramatic rise in circulation; between 1832 and 1836, the combined circulations of the New York dailies quadrupled from 18,200 to 60,000.

68

The growing commercialization of the press entailed both positive and negative effects. News reporting and editing became more professionalized and the newspapers less blatantly biased. On the other hand, the number of newspapers, the variety of their viewpoints, and the detail with which they covered politics all gradually declined. These developments, however, remained in their early stages during the first half of the nineteenth century.