Vodka Politics (47 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

According to Karl Marx, communist revolution was the inevitable response to the hardships of industrial capitalism. So the only socialist civilization ever envisioned was an industrial one. The Bolsheviks were well aware that their Russia

was overwhelmingly rural and understood the need to industrialize rapidly—the bigger and heavier the industry, the better. Even as the Soviets recovered from war and famine, ambitious plans were devised to accelerate productivity and make the young state militarily self-sufficient, culminating in the First Five-Year Plan in 1928. To meet such goals (a year early!) by 1932, the economic planning agency Gosplan dictated a ludicrous expansion of iron, steel, coal, and oil output—necessary to build armaments, tanks, tractors, railways, and heavy machinery.

Rapid industrialization required two things that Stalin lacked: money and men. More to the point, it necessitated a source of investment revenue and a competent, disciplined urban workforce. Vodka was crucial to both—and Stalin knew it.

19

A communist pariah in a still-capitalist world, the Soviet Union could not get investments or loans from abroad, so they turned instead back to the vodka trade that had provided inexhaustible revenues to their imperial predecessors. If Stalin is to be believed, the move was done primarily for industrialization. “When we introduced the vodka monopoly, we were facing the alternatives: either go into bondage to the capitalists, having ceded to them a number of our most important plants and factories, getting in return the necessary funds to allow us to carry on; or to introduce the vodka monopoly in order to get the necessary working capital for developing our own industry with our own resources, and avoid going into foreign bondage.”

By the end of 1927, it was already paying dividends: “The fact is, immediately abandoning the vodka monopoly would deprive our industry of over 500 million rubles, which could not be replaced from any other source,” Stalin then claimed. That translated to ten percent of all state revenues. To hear him explain it, the monopoly was only a temporary improvisation, and “it must be abolished as soon as we find new sources of revenue in our national economy for the further development of industry.”

20

Apparently Stalin never found those new sources of revenue. As vodka production rapidly increased, so too did alcohol’s contributions to the state budget: rising from a mere 2 percent of Union revenues in 1923–24 to 8.4 percent in 1925–26 and fully 12 percent of all income by 1927–28.

21

These increases resulted in quite a problem of national drunkenness. In a letter to the liquor monopoly Gosspirt, the finance ministry admitted that vodka revenues could barely cover the harm it was causing the country. From 675 million rubles in 1927–28, by 1928–29, the letter projected, “we should net 913.7 million rubles and 1,070 million by 1929/30. Yet the demands of common sobriety require minimum budgetary revenues from vodka. Herein lies our present trouble and future problems.”

22

Herein, again, lies vodka politics.

The finance ministry was right to focus on sobriety. Drunkenness bedeviled efforts to build the disciplined, urban workforce needed to man the new assembly lines, iron works, railways, and hydroelectric stations—all built on a gigantic scale. Certainly forced labor provided one answer, as the greatest engineering accomplishments of the Stalin era—from the White Sea Canal to the towering spires of Moscow State University—were largely built by the slave labor of those condemned to the gulags. But the incredible growth of the urban working population—from 26 million in 1926 to 38.7 million in 1932—primarily reflected the forced migration of peasants from the countryside: the same conservative peasantry the communists long suspected of potential counterrevolution; the same rural peasantry that long persisted in distilling their grain into

samogon

rather than giving it to the state; the same illiterate and unskilled peasantry that had a long tradition of insobriety.

23

By the late 1920s—with Stalin becoming the unscrupulous tavern keeper for all of Soviet society—the People’s Commissariat of Labor, or Narkomtrud, suffered the biggest hangover. With the flood of uneducated and intoxicated peasants into the workforce Narkomtrud charted a staggering drop in workplace discipline. Few workers showed up on time, and when (or if) they did, they were often hungover. They could not work the machinery and did not care to learn, a situation leading to waste, broken equipment, and shoddy products. Narkomtrud was inundated with reports of absences, drinking on the job, drunken fistfights, and assaults on factory managers and party representatives.

24

Rank-and-file communists hardly set the example of the honest, sober new “Soviet man” the ideologues had envisioned. As the recruitments of the 1920s transformed the Communist Party from a small vanguard of intellectuals and activists to a mass party of millions, rampant alcoholism became a major problem for the party itself. Since drunkenness was considered a petit bourgeois remnant of the past, the party regularly purged itself of “drunks, hooligans, and other class enemies” in the interest of party discipline.

25

To promote workplace discipline, the Soviets turned to propaganda. In 1928, Gosplan co-founder Yury Larin and famed theorist Nikolai Bukharin spearheaded a diverse group of politicians, war heroes, writers, poets, and academics in creating the Soviet Union’s first temperance organization, the Society for the Struggle against Alcoholism (OBSA).

26

The OBSA focused on improving the dismal conditions in the sprawling urban slums, which were eerily reminiscent of the grinding poverty and desperation of capitalist Europe’s industrial working classes that Marx and Engels decried a century earlier. Temperance admonishments peppered the pages of

Pravda, Izvestiya

, and a new monthly journal,

Trezvost i kultura

(

Sobriety and Culture

).

27

Yet temperance was never an end in itself—it was only a means to greater discipline necessary for industrialization. Such well-meaning temperance activism was tolerated only so long as it did not interfere with Stalin’s greater aspirations. In this respect, Soviet temperance was doubly doomed.

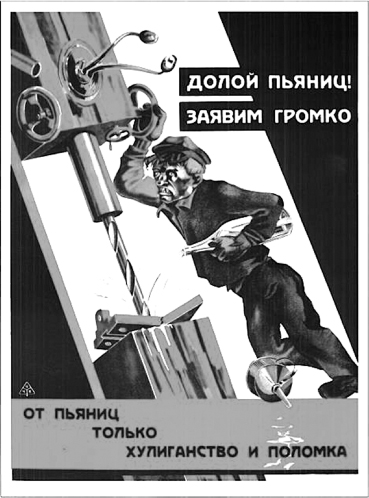

D

OWN WITH

D

RUNKARDS

! (1930). “Down with drunkards we say loudly: from drunkards come only hooliganism and breakage.” I. Yang and A. Cernomordik.

Kate Transchel—the leading historian of the OBSA—noted “it is significant that Bukharin, who is generally accepted as the party’s leading theorist after Lenin’s death, chose the anti-alcohol movement through which to attack the problems of Soviet society.”

28

It is also significant that within a few months of founding the OBSA, Bukharin (who was Stalin’s last rival within the Politburo) was disgraced as part of the “Right Opposition.” A decade later—suffering the same fate as Kamenev and Zinoviev’s “Left Opposition”—Bukharin was put on show trial on trumped-up sedition charges, tortured into confession, and executed.

With Bukharin gone, the OBSA stood little chance against Stalin’s unquenchable need for more vodka revenues. In 1930, the society was scuttled, and the problem of alcoholism in the Soviet Union quietly disappeared from official discourse.

Trezvost i kultura

abruptly explained to its readers that there was no longer a need to combat alcoholism since “the socialist way of life would destroy

drunkenness.” Beginning with the very next issue, the magazine would be known as

Kultura i byt—Culture and Lifestyle

—which vocally denounced OBSA founders Larin and Bukharin as antigovernment demagogues.

29

Just like Stalin brushed aside Bukharin as an impediment to his single-minded quest for absolute power, he also brushed aside the OBSA as an impediment to his all-out expansion of the industrial and military might of the Soviet state. In complete opposition to his publicly professed desire to “completely abolish the vodka monopoly,” on September 1, 1930, Stalin wrote in a letter to Vyacheslav Molotov, then the loyal first secretary of the Moscow Communist Party, that

I think vodka production should be expanded (

to the extent possible

). We need to get rid of a false sense of shame and directly and openly promote the greatest expansion of vodka production possible for the sake of a real and serious defense of our country. Consequently, this matter has to be taken into account

immediately

. The relevant raw material for vodka production should be formally included in the national budget for 1930-1931. Keep in mind that a serious upgrade of civil aviation will also require a lot of money, and for that purpose we’ll have to resort again to vodka.

30

Two weeks later, the question of maximizing the liquor output was taken up by the Politburo. Strangely, archival records of the Politburo’s discussions and decisions of that day were submitted to the so-called special file—reserved for the most secret documents in the Soviet Union. Now housed in the Presidential Archive of the Russian Federation, these documents remain highly classified and strictly off limits to historical researchers.

31

Vodka And Collectivization

If industrialization was the foremost ideological challenge of the late 1920s, the primary practical challenge was the peasantry. Here too the issue turned on vodka. During the reconstruction from war and famine, agricultural productivity rebounded more quickly than industrial productivity. This makes sense, since you don’t have to rebuild a field like you do a factory: simply plant the seeds, till the soil, and come fall you’ve got crops. In the past, there was an urban-rural trade cycle: the peasants sold their grains to buy goods manufactured in the cities. Only now there was nothing to buy because the factories were still in ruins. By 1923, the Soviet Union was in the middle of what Trotsky dubbed the “scissors crisis”: the prices of scarce industrial goods were rising while the cost of the

now-plentiful agricultural goods was plummeting—when plotted on a graph, the diverging prices looked like the two blades of an open pair of scissors.

According to most historians, rather than get next to nothing for their crops, the peasants simply hoarded them. That is a half-truth. Since piles of grain easily rot and are difficult to conceal from the authorities, most peasants didn’t just hoard their grain; they distilled it. Bottles of

samogon

did not spoil, they were more easily concealed, and they could be consumed or used to bribe local authorities. Plus, since home-brewed vodka could be sold at a black market price that was far higher than the abysmally low price of grain, the terms of trade became more even. Consequently, every time agricultural and industrial prices diverged, the Russian countryside was flooded with illegal alcohol, even as foodstuffs disappeared from store shelves in the cities.

32

In the early 1920s, the government first tried to crack down on bootleggers throughout the countryside. When it became apparent that the crackdown did not work, they threw up their hands and reimplemented the vodka monopoly, which also generated the resources needed for industrialization. As Chamberlain described it:

The official justification for the legal return of vodka is that all efforts to prohibit it broke down as a result of the widespread drinking of

samogon

, or home-brewed vodka, which sometimes attained an alcoholic strength of 70 per cent and was considered more harmful than vodka, both in its physical effects and in its waste of grain. The euphemistic explanation for the return of vodka is that it is a “means of fighting

samogon

.” While this consideration doubtless carried weight, the action of the government was also influenced by the fact that the Russian peasant is reluctant to part with his grain until he sees something which he may buy with the money which is paid him. It is expected that vodka will help to full up the void which is created by the shortage of manufactured goods.

33

Even with a functioning—and lucrative—vodka monopoly, the artificially low price of grain produced another so-called scissors crisis in 1927. Although grain production had almost recovered to prewar levels, less than half was being brought to market, leading to food shortages in the cities and

samogon

surpluses in the countryside. A 1927 official study estimated that the rural Russian population annually consumed an average of 7.5 liters of

samogon

per capita—four times their consumption of legal state vodka.

34

This was the dilemma that American satirist Will Rogers described as driving the Soviet government cuckoo. “If you got that Vodka for a companion you got a mighty ally on your side when it comes to forgetting your troubles,” Rodgers said of the Russian

peasantry. “They can live on what the raise, and drink the surplus and enjoy it.”

35

By the Soviet government’s own account, illegal distillation was consuming no less than thirty million

pud

(491 million kilograms) of grain every year.

36

Something had to be done.