Vodka Politics (34 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

Not even the army high command was sober. Rather than direct the left flank of the Russian defenses, Lt. Gen. Vasily Kiryakov instead threw a champagne party. Generally described as “utterly ignorant, totally devoid of any military ability and rarely in a completely sober state,” on this day Kiryakov stumbled to his feet and—bottle of champagne in hand—ordered his Minsk regiment to open fire on what he thought was the French cavalry. It was actually his own Kiev Hussars, who were decimated by the barrage. Enraged, the Hussar commander had to be physically restrained from running Kiryakov through with his sword. With no confidence in their drunken commander, the Minsk regiment also retired—in some cases without ever firing a shot at the enemy. In the disorder Lt. Gen. Kiryakov mysteriously disappeared, only to be found hours later cowering in a hollow in the ground. Nearby, British forces discovered a Russian artillery captain sprawled dead drunk in a wagon. The jovial sot offered his captors a swig from his bottle of champagne, which turned out to be empty.

34

The battlefield fiasco rudely upset commander Menshikov’s viewing party, which was abandoned so hastily that the parasols, field glasses, and even the picnic spread were left behind. In Menshikov’s carriage the French found “letters from the Tsar, 50,000 francs, pornographic French novels, the general’s boots, and some ladies’ underwear.”

35

After the disastrous battle of Alma, Menshikov withdrew his army to the interior of the Crimea, leaving the sailors and civilians of Sevastopol to their fate. When riders brought news of the catastrophe to Tsar Nicholas in St. Petersburg, he brooded in bed for days, “convinced that his beloved troops were cowards led by idiots.”

36

Things were just as bad in the imperial navy in Sevastopol. Consider for instance the heart of the naval citadel, Malakhov Hill: towering over Sevastopol

Bay and its nearby estuaries where the mighty Russian fleet was anchored, it was the linchpin to the city’s defenses. Today, Malakhov Hill is a popular city attraction: a serene, wooded park and open-air memorial complex replete with an eternal flame. Given the hill’s strategic and historic importance, surely this Malakhov fellow after whom it is named was some legendary military hero, no?

Actually… no.

Mikhail Malakhov was a lowly ship’s purser in the tsarist navy in charge of bookkeeping and buying provisions. His position allowed him to acquire great quantities of

charka

liquor on the navy’s tab, which he then sold for immense personal profit. Even after being court-martialed for such corrupt abuses, Malakhov used his connections with shifty procurement officers and bootleggers to open an illegal, ramshackle (but extremely popular and lucrative) vodka shop, built into the side of the hill that now bears his name.

37

Following the defeat at the Alma River, Malakhov Hill was the city’s last defense against the allied invaders. With the Russian army in flight, the entire population of Sevastopol—military and civilian, men and women, police and prostitutes—dug trenches, built barricades, and prepared for the imminent attack. To slow the allies’ seaward advance, Russian warships were scuttled in the harbor, many fully stocked with armaments and provisions. Demoralization, insubordination, and despair swept the city. To make matters worse, the discovery of a large storehouse of liquor wharfside resulted in a three-day drunken rampage.

“A perfect chaos reigned throughout the town,” Chodasiewicz recalled. “Drunken sailors wandered riotously about the streets, and in some instance shouted that Menshikov had sold the place to the English, and that he had purposely been beaten at the Alma.”

38

In a quixotic effort to restore sobriety and confidence, Vice Adm. Vladimir Kornilov—the fleet’s chief of staff—instituted emergency anti-alcohol measures by closing vodka stores, taverns, hotels, and restaurants, actions ultimately having “little or no effect in restraining the populace from drunkenness.”

39

On October 17, 1854, the artillery barrage began. In that initial battle a British round detonated a Russian magazine, killing Adm. Kornilov, ironically, atop Malakhov Hill. Today, a monument to Kornilov’s sober heroism crowns the hill named after the city’s corrupt vodka dealer.

The siege of Sevastopol continued for months—the tense stalemate occasionally interrupted by salvos of artillery or an occasional ground attack—while conditions in the city deteriorated. Most residents drank a tumbler of vodka with breakfast and dinner and even more in-between. In his

Sevastopol Sketches

, a young Count Tolstoy described how officers spent their off-duty hours drinking, gambling, singing, and carousing with what few prostitutes remained in the city. The heavy drinking was always ramped up just before an attack in order to bolster the soldiers’ courage. Stammering into battle, the unsteady soldiers made easy targets. “The army that came out of Sevastopol to attack the other day… were all drunk,” recalled one British regimental paymaster. “The hospitals smelt so bad with them that you could not remain more than a minute in the place and we were told by an officer who they took prisoner that they had been giving them wine till they had got them to the proper pitch and asked who would go out and drive the English Dogs into the sea, instead of which we drove them back into the town.”

40

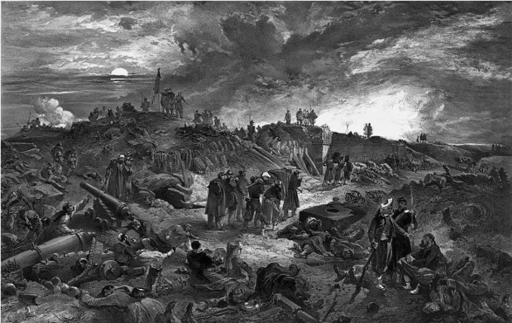

L

ITHOGRAPH

D

EPICTING THE

F

INAL FRENCH

A

TTACK ON THE

M

ALAKHOFF

H

ILL

, 1855 Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division/William Simpson.

Still, over the ensuring months the heroic defenders of Sevastopol repulsed five separate allied assaults on Russian positions, inflicting heavy losses on both sides. Finally, on their sixth assault, the French successfully overran the city’s last defenses and captured Malakhov Hill on September 8, 1855. The city of Sevastopol surrendered the following day.

The Crimean War was an embarrassing defeat: Russian battle casualties topped one hundred thousand, with another three hundred thousand succumbing to disease, malnourishment, and exposure.

41

Among those casualties might be listed Tsar Nicholas I himself, whose military fixation and despair took a dramatic toll on his health. In the spring of 1855, while reviewing troops departing for Crimean battlefields, the tsar contracted pneumonia and died shortly thereafter.

Soon diplomats mingled in Paris while negotiating peace terms, as did former belligerents on the battlefield. A diary entry of British soldier Henry Tyrrell dated Sunday, April 6, 1856, paints a vivid picture:

The great objects of attraction to-day were the Russians, who…wandered into every part of our camp, where they soon made out the canteens. By one o’clock there were a good many of them “as soldiers wish to be who love their grog.” A navvy [British manual laborer] of the most stolid kind, much bemused with beer, is a jolly, lively, and intelligent being compared to an intoxicated “Ruski.”… Their drunken salute to passing officers is very ludicrous; and one could laugh, only he is disgusted at the abject cringe with which they remove their caps, and bow, bareheaded, with horrid gravity in their bleary leaden eyes and wooden faces, at the sight of a piece of gold lace. Some of them seemed very much annoyed at the behavior of their comrades, and endeavoured to drag them off from the canteens; and others remained perfectly sober. Our soldiers ran after them in crowds, and fraternised very willingly with their late enemies.

42

Indeed, the French, British, and even the Turkish soldiers happily drank with their newfound Russian friends. At the end of each night’s revelry the Russians returned to their encampments across the deep Chernaya River, which could be crossed only by means of fallen trees—quite a challenge even when sober! Cossack patrols used ropes to pull drunks half-dead (and occasionally fully so) from the water. “Down they came, staggering and roaring through the bones of their countrymen (which in common decency I hope they will bury as soon as possible), and then, after elaborate leave-taking, passed the fatal stream,” Tyrrell wrote. “General Codrington was down at the ford, and did not seem to know whether to be amused or scandalized at the scene.”

The British posted guards along the roads to keep “all the drunken Ruskies out of the town” and sentries along the cliffs and harbors “to prevent them coming in after their jollification at the bazaar.” And still they came—especially the more affluent Russian officers who bought huge quantities of champagne and liquor that cost half as much in the allied camps as in the Russian ones.

43

Clearly the embarrassment of pervasive drunkenness contributed to humiliating military defeat in Crimea. Alexander II’s consequent political reforms—abolishing serfdom and the corrupt tax farm—did not stop the state from profiting from the drunkenness of its people, including the lowly peasant conscripts. Only in 1874 did Russia finally scrap Peter the Great’s village quota system for universal conscription, requiring six years of military service for all

men. Unfortunately, this reform also universally conscripted Russians to the bottle: even peasants who never touched vodka before enlisting often returned home as drunkards. Later studies found that some 11.7 percent of St. Petersburg workers began drinking vodka only in the military.

44

Ultimately, universal conscription became just another tool in the alcoholization of Russian society.

Even in peacetime alcoholism in the ranks was epidemic. Expressly blaming the vodka ration, one military physician estimated that seventy-five percent of the soldiers in infirmaries were there due to alcohol poisoning and that between ten and forty-four percent of all military deaths were attributable to alcohol. “Was he drunk?” became the medic’s standard first question for treating any accident or ailment. But the military brass wasn’t listening. At the dawn of the twentieth century, the imperial ministry of war flatly denied that there was any alcohol problem at all, much less one caused by the troops’ vodka rations.

45

The insobriety and ineptitude of the tsarist military was a disaster waiting to happen. And if Crimea suggested that alcohol was a major problem, Japan proved it.

Stumbling Toward Defeat In The Far East

Just as the imperial double-headed eagle peered both west toward Europe and east toward Asia, by the early twentieth century Russia’s imperial ambitions brought it into conflict not only with European powers but increasingly with Asian ones as well. Following combined efforts to suppress the Chinese Boxer Rebellion of 1900, the empire of Japan held much of Korea while Russia occupied Chinese Manchuria, including Port Arthur (today, Lüshunkou) on the Liaodong Peninsula—Russia’s coveted ice-free port on the Pacific. Previously occupied by Japan before an eight-nation European alliance forced its concession to Russia,

46

Port Arthur was crucial to propagating influence in the Far East. The opening salvo in the Russo-Japanese War was a surprise nighttime torpedo attack on the Russian fleet anchored at Port Arthur on February 8, 1904. Japan hoped to strike quickly before Russian reinforcements could arrive from Europe across the still-incomplete Trans-Siberian Railway.

Reinforcements were slow in coming and not simply due to Russia’s anemic infrastructure. Mobilizing hundreds of thousands of unwilling sons, husbands, and fathers to fight and die in the Far East unleashed drunken pandemonium at assembly points. Torn from their villages and families, some committed suicide rather than enlist. Officers shot themselves with rifles, slit their own throats with knives, hung themselves, or worse: in his memoirs, military physician Vinkenty Veresayev described how a widower with three dependent children broke down before the military council.

“‘What shall I do with my children? Instruct me what to do! They will all die from starvation without me!’”

“He acted like a madman,” Veresayev recalled: “shouted and shook his fists in the air. Then he suddenly grew silent, went home, killed his children with an axe, and came back.

“‘Now take me’” said the recruit. “‘I’ve attended to my business.’

He was arrested.”

47

Beyond such extreme cases, the tearful send-offs at assembly points often turned into orgies of mayhem, as recruitment officers corralled drunken conscripts with bayonets. With surprising frequency commanders were overwhelmed by the drunken masses, as vodka-fueled mobs ransacked local taverns and businesses and murdered recruitment officers.

48