Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty (16 page)

Read Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty Online

Authors: Bradley K. Martin

Tags: #History, #Asia, #Korea

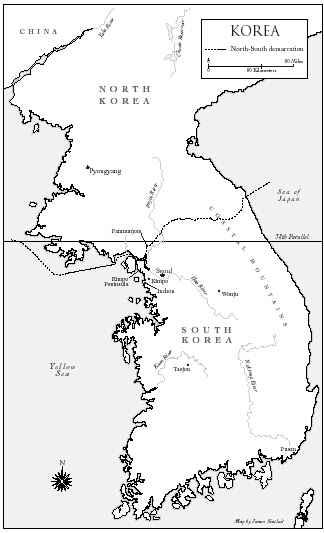

Moscow also set in motion shipments of the needed military equipment. Once everything had been shipped and the North Korean forces readied to launch their invasion, the North had twice as much manpower and artillery as the South and at least a six-to-one advantage in aircraft and tanks, according to Soviet estimates.

In the plan, the invasion was referred to as a “counteroffensive.” Trying to avoid being branded the aggressor, Pyongyang for decades to come would

maintain consistently—for both external and internal consumption—that the South had invaded first and the North had merely responded.

Yu Song-chol said he passed the invasion plan up to Kim Il-sung. Kim then signed off on the plan, writing “Concur.”

1

On June 25 at 4 A.M., the North Korean forces opened fire. The official propaganda over the years that followed repeated ceaselessly the outright lie that Kim “never for a moment relaxed his struggle to prevent war and achieve national unification peacefully” while South Korea and the United States answered him by launching “a cursed, criminal, aggressive war, for which they had long been preparing.”

2

In Seoul, it was not as if an attack were totally unexpected. “We knew better than almost anywhere in the world that the Communists planned to invade,” said Harold Noble, an American diplomat based in Seoul. “But it had been coming since 1946.” The passage of time had lulled both Koreans and Americans in the city. Like people living on the edge of a volcano, “we knew it would explode some day, but as day after day, month after month, and year after year passed and it did not blow up, we could hardly believe that tomorrow would be any different.”

3

Thus, when the shooting started on that Sunday morning of June 25, the Southern forces had their guard down just as the invasion planners had hoped. Many soldiers were away on weekend passes,

4

and others were sleeping when the all-out Northern artillery and tank attack hit them.

Receiving situation reports in a natural cave near Pyongyang that they had turned into their command post, Maj. Gen. Yu Song-chol and other North Korean military brass were astonished at how easily the Southern forces collapsed. The Korean People’s Army’s 150 Soviet-made T-34 tanks frightened Southern soldiers, who fell back in helpless confusion as seven Northern divisions surged down to Seoul.

Yu recalled just a couple of lapses at that stage in the otherwise highly successful invasion plan. One tank unit was delayed traversing mountain terrain more rugged than the planners had counted on. (The planners after all were not locals but hailed, one and all, from the Soviet Union.) The KPA First Division’s communications system broke down and a weapons storage facility blew up, like-wise causing delays. A furious Kim Il-sung ordered the First replaced by the Fourth Division and decreed death by firing squad for the First Division commander, Maj. Gen. Choe Gwang, an old comrade from Manchuria guerrilla days. The army’s frontline commander persuaded Kim to rescind the order.

5

(After at least one more run-in-with Kim, in 1968,

6

Choe nearly four decades later, in 1988, was named chief of the general staff of the KPA. In 1995, with the death of Marshal O Jin-u, the defense minister, Vice-Marshal Choe became the top-ranking North Korean military man.)

***

When the North Koreans marched into Seoul in triumph just three days after the initial attack, Rhee’s Southern forces retreated south-ward. The Northerners hoped the war was all but won. In Korea, all roads led to Seoul. Pyongyang expected that losing the city that had been the capital for more than five centuries would put pressure on the Rhee regime to throw in the towel.

Based on a rosy prognosis from Pak Hon-yong, the invasion plan had anticipated that Southerners would help the invaders by rising massively against their rulers. Having been the leader of South Korea’s communists before fleeing to the North, Pak was eager to restore his power base through an invasion. He had assured Kim—and Stalin—that two hundred thousand hidden communists in the South were “ready to rebel at the first signal from the North.”

7

In Seoul nothing of the sort happened. To be sure, there were happy people among the Seoul populace, wearing red armbands and running about to cheer their liberators. Happiest of all may have been prisoners who shouted, as the North Koreans threw open the prison gates, “Long live the fatherland!” Soon the streets were bedecked with posters depicting Kim Il-sung and Stalin.

8

The invasion went over well with pro-communists such as an ice cream peddler who led some neighbors in chanting against the Rhee “clique” and confiscated for use as his family living quarters a mansion belonging to a former mayor.

9

But after the initially well-behaved occupiers began rounding up and killing Southern “reactionaries,” even the shouts of support started to die down.

10

Yu traveled to Seoul and was surprised to see that “the people on the streets were expressionless to us. When we waved our hands to them, there were few who cheered for us.”

11

The operations plan called for North Korean troops to advance nine to twelve miles a day and take over the whole peninsula in twenty-two to twenty-seven days.

12

The Northerners made the huge mistake of halting their advance in Seoul for two days of rest and celebration—giving the South’s forces time to regroup. And with further communications breakdowns, the post-Seoul plans proved unworkable in some aspects. Guerrillas did help the Northern troops in some battles. But the massive uprising Kim had counted on did not occur in the hinterland, any more than it had in Seoul and vicinity

13

Still, the eager Northern forces rolled down the peninsula.

Mean-while, Kim’s propaganda machine swung into action to try to make believers out of the South Koreans. Schoolchildren in North Korean–occupied Seoul learned the catchy “Song of General Kim Il-sung”:

14

Tell, blizzards that rage in the wild Manchurian plains,

Tell, you nights in forests deep where the silence reigns,

Who is the partisan whose deeds are unsurpassed?

Who is the patriot whose fame shall ever last?

So dear to all our hearts is our General’s glorious name,

Our own beloved Kim Il-sung of undying fame.

15

On the home front, morale was high. Only a handful of North Koreans knew that their army had invaded the South. Most believed the North had been the target of a Southern and U.S. invasion, an invasion that the North Korean People’s Army had turned back heroically. Pyongyang’s phony unification appeal just before the attack had fooled Kim’s own people.

In the North, once the “war of national liberation” started, youngsters heeded the volunteer-recruitment slogan: “Let’s all go out and give our lives!” Kang Song-ho, an ethnic Korean from the USSR-who was living in North Korea when the war broke out, appeared on South Korean television many years later and told how he and his friends had become fired up to fight the Southern forces. “At that time, there was a lot of propaganda made about North Korea appealing to South Korea, always offering peaceful unification,” he said. Northern propaganda, as Kang recalled, claimed that “the U.S. had given instructions, and South Korea had already been made into their colony.” Rhee was inciting his men “to go and even eat up the people of North Korea.”

16

Far more serious than the misguided assumption of quick victory was the plan’s second major flaw: the assumption that the United States would stay out. Perhaps that might have turned out to be the case, if not for the Northern forces’ fatal two-day stopover in Seoul. But Kim’s assumption that the United States would not intervene to reverse a fait accompli more likely was mistaken—if he really believed that and was not simply handing Stalin a line to win Soviet support. Because of American policy makers’ assumptions about the meaning of the invasion, response was close to automatic—and there certainly would have been sentiment in the United States in favor of retaking the South even if the North had overrun all of its territory.

Acheson and other American officials assumed that Stalin had a role in the June 25 invasion—a correct assumption, as has been amply proven with the opening of the archives of the former Soviet Union. But the Americans exaggerated the Soviet role, imagining that the Korean invasion was but the first step in an expansionist Soviet plan. They did not know that it was Kim— not Stalin—-who had taken the initiative, and for his own purely Korean purposes. “This act was very obviously inspired by the Soviet Union,” President Harry Truman said in a congressional briefing. Assistant Secretary of State Edward W. Barrett compared the Moscow-Pyongyang relationship to “Walt Disney and Donald Duck.”

17

Complicating matters was the universal tendency to “fight the last war,” a tendency that was reinforced by the currents of domestic United States politics

at the time. Strong memories remained of the negative consequences that had flowed from appeasing the expansionist Nazis at Munich. More immediately, Truman’s Democrats and the Department of State had come under fire from Republicans for decisions and actions that allegedly permitted the “loss” of China: Mao Zedong’s 1949 victory over Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists.

By 1950, conspiracy theorists in a kill-the-messenger frenzy were questioning the loyalty of a host of officials who had doubted Chiang’s viability. Only four and a half months before the North Korean invasion, on February 9, Senator Joseph McCarthy had begun his Red-baiting campaign by announcing in Wheeling, West Virginia, that he held in his hand a list of 205 Communist Party members working in the State Department. For Truman to let the Korean invasion stand—and thus preside over the “loss” of yet another country—-would have made him instant grist for McCarthy’s mill.

Although Truman certainly-was aware of the compelling domestic political factors as he decided on a response in Korea, publicly he stuck to international, Cold War reasoning when he set out to rally Americans and allies to take a stand. “If we let Korea down,” Truman told members of Congress, “the Soviets will keep on going and swallow up one piece of Asia after another.” After Asia, it would move on to the Near East and, perhaps, Europe. The United States must draw the line. Here was an early enunciation of-what came to be called the Domino Theory.

18

It was not long before additional evidence began appearing that suggested the Truman-Acheson assumption about Stalin’s expansionism was off the mark.

19

Korea bordered the Soviet Union, so Stalin naturally preferred a like-minded state there for security reasons. But Stalin’s policy apparently did not call for the unlimited expansion into nonbordering states that many in the West feared—not, at least, for the time being.

20

On the other hand, there has never been much doubt about the accuracy of another Truman assumption: Without swift American intervention, the invaders would overrun all of South Korea. The president acted quickly and decisively. A United Nations resolution, engineered by Washington just two days after the invasion, demanded that the Northern troops go back behind the 38th parallel. Wrapped in the UN mantle, Truman committed not only air and sea support but ground troops to help the beleaguered South Koreans. Lead units of the U.S. Army Twenty-fourth Division, stationed in Japan, landed on July 1, just six days after the invasion, signaling a full American commitment to the war. A UN command ultimately combined the combatant troops of sixteen nations, with thirty-seven others contributing money, supplies and medical aid.

Acheson’s successor as secretary of state, Dulles, later explained the decision this way: “We did not come to fight and die in Korea in order to unite it by force, or to liberate by force the North Koreans. We do not subscribe to the principle that such injustices are to be remedied by recourse to war. If indeed that were sound principle, we should be fighting all over the world and

the total of misery and destruction would be incalculable. We came to Korea to demonstrate that there would be unity to throw back armed aggression.”

21

Kim Il-sung could point his finger at underlings for misleading him regarding the Southern response, and for letting the People’s Army troops stop to rest after taking Seoul. However, miscalculating American capability and intent was a higher-level responsibility. Yu Song-chol said some ranking North Korean officials had warned that the United States might intervene— but Kim had dismissed their warnings as defeatism.

22

With the North Korean attack, and Truman’s decision to defend South Korea, Americans who never had thought much about far-off Korea and were not even quite sure how to pronounce it were suddenly hearing a great deal about it. I was among them, a third-grade elementary school pupil at the time the war broke out. Comic books quickly began featuring GIs in the John Wayne mold fighting ferocious communist “gooks.”

23

By the third year of the fighting Ken Pitts, a fellow pupil in my Georgia Sunday school class, had made a weekly ritual of praying: “Lord, be with our boys in Ko-rea,” drawling out the first syllable for an extra beat or two.