The Worst Hard Time (31 page)

Read The Worst Hard Time Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

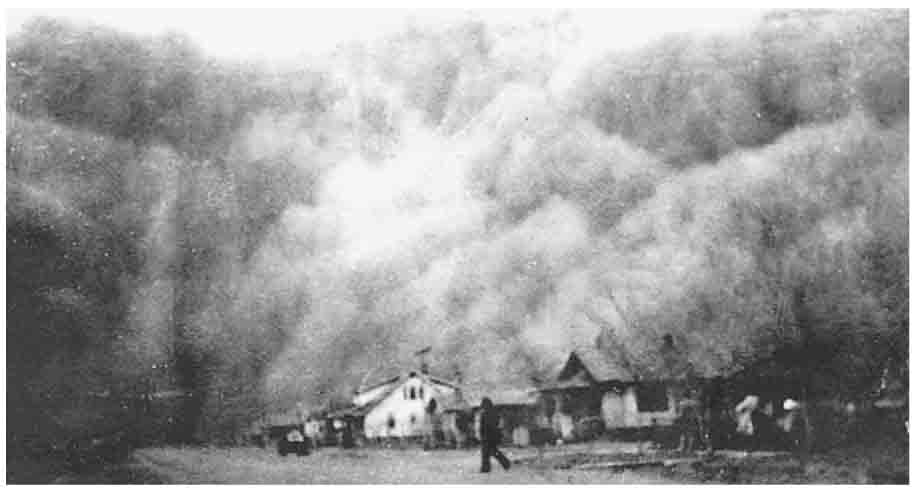

Black Sunday, Liberal, Kansas, 1935

The shot ran in newspapers all over the world, one of the few news service photographs taken of Black Sunday as it unfolded. Geiger estimated the cloud's height at several thousand feet. And while he initially thought it was black, he wrote in his notes that it appeared to be blue gray as it rolled over Cimarron County. In front of it were columns of dust, which looked like smoke, slightly lighter than the main duster. They got back in the car and sped ahead, trying to outrun the cloud, up to sixty miles an hour on the dirt road. It was not fast enough. They saw the road narrow like a tunnel before it disappeared altogether. Geiger slammed on the brakes and turned on the car lights. They sat in the black. After half an hour, they tried to move forward. Geiger braked again, swerved, trying to avoid a family of five that was standing in the road, looking for help. The car went into the ditch, just missing the people.

They pushed the car out, packed the family inside, and resumed as the blizzard lashed at them. In Boise City, the Crystal Hotel was filling up, and there was no way to see who was who or where to go. People crowded into the lobby, a room where bright-faced suitcase farmers once spent their earnings on the biggest steak on the menu. A crowd of scared, dusted exiles gathered around the weak lights of kerosene lamps. They wanted news. What was going on? Where had this come from? When would it end? What did it mean? Geiger had no answers. He wanted only to get back to Denver in time to get the AP pictures out. His car had shorted out. He offered fifty dollars to anyone who could drive him back to Denver.

Thomas Jefferson Johnson was walking home from the Lucas double funeral when the storm hit. Johnson was tall and tough, a homesteader who came west in a covered wagon from the Ozarks and established a dugout on a quarter-section. Johnson was just half a block from home when the blizzard overwhelmed him. He fell to the ground, fumbled for something to hold on to, tried to get his bearings. It was worse than either of the twisters he had lived through, worse than hailstorms that destroyed his crops in the past, as if all of No Man's Land was heaved up and collapsed. Felled by the duster, he crawled forward, crossing the road on his belly. Disoriented in the

blackness, he moved on his hands and knees one way, which he thought would lead him to the house. But it led another way, and he never found it. The heavy sand blew up his nose and got into his eyes, burning. He crawled about six blocks away from the house, fumbling over hard ground and drifts, until he found a shed. It felt as if hornets had stung his eyeballs. Heavy sand was lodged under the lids and against the eyes. He rubbed them for relief, but that only wedged the dirt deeper. When Johnson's family found him later in the evening, his eyes were full of black dirt and he said he could not see. He went blind on Black Sunday, and his vision never recovered.

A few doors away from the Johnson house, Hazel Shaw was packing for the next day's burial of her baby when light was snuffed from the house. A four-year-old niece, Carol, was staying with them for the afternoon, playing around the little apartment attached to their funeral home. Hazel reached out blindly, trying to find the child. Every time she touched a doorknob or metal object, she was jolted by electricity.

"Carol...? Carol! Where are you?"

Hazel had not slept since she took her dying child east a week earlier. The dust pneumonia, the struggle for life in the hospital, the mean, swift deaths of the baby and of Grandma Lou, and the funeral this afternoonâit had been one slap of sorrow after the other. Through it all, she had tried not to break down. But now, with her little niece missing, it was too much. She bumped into walls and knocked over dishes trying to find the child, the tears coming as the dust swirled through the house, her face streaked with black. What had she done to deserve this? Charles grabbed a large flashlight and went outside. The flashlight was worthless; the beam was able to penetrate only a few feet in the heavy silt of the black blizzard. He called for the child but heard nothing but the squawk of birds. Charles fell to his belly and shimmied along the street. There was slightly more visibility at ground level; the cloud seemed to hang just above the earth. Using this crawl space, Charles moved along the street, counting his arm lengths as a way to measure distance. When he got to a place that he estimated to be the approximate distance of the niece's house, he turned and crawled up to the door. He jabbered, his voice panicky, searching for faces.

"I ... we ... we lost Carol. She's gone! She was playing out front in the yard and then she was gone."

"No. No. It's all right. Is that you, Charles?"

The voices in the dark delivered a flash of good news. Carol was safe. The little girl was with them. She had run home when she saw the cloud creep up on Boise City.

Half a mile away, Roy Butterbaugh, the Boise City newspaper publisher, had just climbed into the seat of the little airplane at the edge of town, his buddy in the pilot's seat. They saw the duster approach and decided not to fly. But as they walked away from the dirt airstrip, the curtain fell on them, and they turned, racing back the other way to the airplane. The blackness caused them to stumble. On the ground, they crawled forward to the plane. They got inside, closed the doors. The plane was latched to the ground by guy wires, but it bucked in the fierce winds, rocking hard.

In the cockpit, the two men were just a few inches apart but could not see each other's face.

Another pilot, the aviator Laura Ingalls, had managed to get aloft before the storm. She was flying over the Texas Panhandle in a Lockheed monoplane, attempting to set a new nonstop flying record for crossing the continent. The plane was sleek with low wings, very

fast. Ingalls was approaching the Oklahoma border when she spotted the moving mountain of dirt. It stretched so far she could not see the rear of it, and it looked several hundred miles wide. Even at its top, where the wind should not be able to hold so many coarse dirt particles aloft, the formation was dark, a deep purple, she thought. Ingalls gunned the engine, ascending for cleaner air. She climbed to 23,000 feet. By then it was obvious: no way could she expect to leapfrog over this duster. She turned the plane around and scouted for a place to land, the record on hold.

Dust storm approaching Johnson, Kansas, April 14, 1935

"It was the most appalling thing I ever saw in all my years of flying," she said later.

The Volga Germans had gone outside after church services, taking in the sun and clean air. Their churches stood, though the paint had been blasted away by the dusters. Their houses, many made of brick and two stories, were monuments to craftsmanship, thrift and order. Above all, the Germans prided themselves on keeping their homes clean. On the Volga, there were laws against unswept sidewalks and unkempt front yards, punishable by lashings in the village square. To have the insides of these New World homes trashed by dusters, to have the walls and ceilings leak dirt, week after week, for years on end, was too much for some of the women. The land around Shattuck on the Oklahoma-Texas border had betrayed them. After four years of drought, the Ehrlichs were out of grain. George Ehrlich, the original settler, had lost his ambition when the grief took hold of him following the death of his little boy, Georgie, on the road near his house. It fell to Willie, his only surviving son, to keep the homestead going. On this Sunday, Willie had his calf out for a walk, looking for grass in a dried-up creek bed. He was wandering the land with his sister and her husband when black columns approached from the northwest.

"You better save that calf," Willie's sister said, pointing to a ravine near a fence line. "Looks like it's gonna be a terrible rain."

They had lived on the High Plains long enough to know that when a swollen, dark cloud formation burst and fell on dry land, the runoff could pump up a slit in the earth. Flash floods took almost as many lives as did prairie fires and twisters.

"That's no rain cloud," Willie said.

He had the calf in his arms when the dirt cloud hammered them. Knocked to the ground, Willie coughed up dirt, hollered for his sister and brother-in-law, and felt around for the animal. He rose to his feet and walked just a few steps before he fell again. The fence line was nearby. Willie found the prickly tumbleweeds balled up along the lengths of cedar and followed the line, figuring it would lead to the barn. Hand over hand, he moved along the fence, splinters jamming his palms and elbows, inching along until he ran out of wood. He was where the barn had to be. He knew every inch of this land. And yet, he reached out in space and touched nothing. Ehrlich stumbled along and felt a hay baleâhe was in the barn after all. The storm had blown open the door. He huddled in a corner and waited until near midnight, when some shape and shadow returned to the world. He never found his calf.

After they had cleaned all four hundred square feet of their house, giving the two-room shack a shine like it had not seen since they moved in, and after each of the three children had taken a bath, the White family in Dalhart got ready for evening church services. Sure, they wore clothes handed out by the government, and shoes that had been restitched by the Mennonite cobbler brought into town by the relief ladies, but they were clean for once. Bam put on a shirt that smelled of springtime and waxed the tips of his handlebar mustache. Lizzie had been talking for years about moving out of Dalhart, and these last months had nearly broken her. When the wind blew straight for twenty-seven days in March, accompanied by dusters more reliable than rain, Lizzie started to crumble. She cried until the warm, salty mist of her tears muddied with dust, and she talked every day about a place where they could find a pool of cool water, a grove of flowering trees, air that would not throw shards of earth at the family. But they were stuck, like other Last Chancers. Bam was old, in a place where the years could dent a man well before his time was up. What could a gnarled cowboy do in a broken land? He dragged home meat sometimes from the government cattle kills, and he coaxed eggs from hens. He planned to get some corn and hay going.

Their feisty son, Melt White, had just found out from an aunt about the Indian blood in him. At first he tried to deny it to himself. Indians had all been run off the Llano Estacado, and nobody had a nice word for them. The kids at school gave him a bad time about his skin. They called him "Mexican" and "nigger." He knew now he was Indian because his daddy said it was so and that's why they could ride horses better than most, and also why the old man could not handle liquor. Cherokee, Irish, and English on his daddy's side, Apache and Dutch on his mama's side. He'd been told it was a disgrace to be part-Indian, especially Apacheâthey were the meanest, sorriest tribe in the world, that all they wanted to do was drink and fight, his relatives said. Melt was a teenager and starting to think about getting out.

"I'm just a boiled-up Indian," he told a friend. "I don't belong here."

He wanted to go someplace where he could ride horses like his daddy had done. The family house was a bare huddle of boards and tarpaper: no trees, no lawn, the garden dead from static electricity.

Melt was outside when he looked north and saw a long line of black drawn across the prairie. It seemed like it was a mile high and moved quickly. Just ahead of it, the sun lit up the brown fields of Dallam County and the streets of Dalhart. Birds flew low, in a straight line, next to swarming insects. He ran inside.

"We ain't gonna be able to go to church," said Melt.

"Why's that?" his daddy asked.

"Come outside and have a look."

Bam White needed only half a look. There was no time to give the storm a proper stare. He hurried back inside the house.

"Close them windas!"

They wetted down bed sheets that had just been cleaned and covered the windows. Most dusters blew sideways, the dirt seeping through the walls in horizontal gusts. This one showered from above, the black flour slithering down the walls. In the darkness, while fumbling for the lamp, Bam hit his knees on the edge of the stove. The electric shock hurt worse than the knee slam. Melt touched his nose with his fingers, just to reassure himself that his hands were still connected to his body. He could not see his fingers.

Half a mile away, Doc Dawson had been sitting on the porch swing with his wife. It was truly summerlike that afternoon, the temperature in the upper eighties. Every window in the house was open. The blizzard fell on Dalhart about 6:20

P.M.

A Rock Island Railroad train that was approaching the terminal came to a sudden halt; the conductor had doubts about continuing in the soup of black. Cars died on the main street in front of the DeSoto Hotel and offices of the

Texan

and the Coon Building. Uncle Dick Coon was getting ready for a Sunday meal. He never saw the food. Drifters who had just finished eating beans at the Dalhart Haven mumbled in confusion. A nine-year-old boy walked in a circle, crying, less than half a block from his house. He screamed: "Help me, please! I've gone blind."