The Worst Hard Time (23 page)

Read The Worst Hard Time Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Later that year, the government men offered contracts to wheat farmers if they agreed not to plant next year. This idea seemed immoral and not the least a bit odd to people when they first heard about it. Like the cattle slaughters, it was a part of a Roosevelt initiative to bring farm prices up by reducing supplyâforced scarcity. In the end, many farmers were not going to plant anywayâwhat was the use, with no water?âso the idea that they could get money by agreeing to grow nothing was not a hard sell. More than twelve hundred wheat farmers in No Man's Land signed up for contracts and in turn got a total of $642,637âan average of $498 a farmer. Thus was born a subsidy system that grew into one of the untouchable pillars of the federal budget. It was designed for poor grain growers, one foot in foreclosure, near starvation, pounded by dirt. And plenty of farmers were starving.

"I fell short on my crop this time," a farmer from Texas wrote President Roosevelt in late 1934. "I haven't got even one nickel out of it to feed myself and now winter is here and I have a wife and three little children, haven't got clothes enough to hardly keep them from freezing. My house got burned up three years ago and I'm living in just a hole of a house and we are in a suffering condition."

For people who had been without income since 1930, a check of $498 was a sufficient enough windfall to keep them on the land, though not enough to run a farm for another year. It allowed them,

though, to exist. They paid just enough of their overdue taxes, and just enough of the outstanding interest on their bank loans, and just enough to get seed, to keep them from closing the door and walking away. Without the government, all of Cimarron County might have dissipated in the dust in 1934. For that year, the government bought 12,499 cattle, 1,050 sheep, and gave out loans to 300 farmers. The government estimated that 4,000 of the 5,500 families in six counties of the Oklahoma Panhandle were getting some form of relief, from a few dollars a week to work on road crews to forced scarcity payments. All told, nearly a million dollars came from Washington to the distant corner of No Man's Land.

Hugh Bennett thought if he could rest the land in some of these blowing prairie states, nature might have a shot at a comeback. Bennett was trying to change agricultural history. One idea was to put new growth on the bald grasslands, a restoration project that had never been tried before on such a scale. His other idea was to get individual farmers to break down their barriers of property and think beyond their fence lines. It wasn't enough for one farmer to practice soil conservation if his neighbor's land was blowing. Bennett wanted people to see the whole of the living plains, not the squares of ownership.

Bennett put one of Roosevelt's alphabet agencies, the Civilian Conservation Corps, to work on some of his early demonstration projects, and tried to inspire them with a sense of urgency about their mission.

"We are not merely crusaders," he said at a rally of CCC workers, "but soldiers on the firing line of defending the vital substance of our homeland."

Oklahoma's governor, Alfalfa Bill Murray, was furious as the first benevolent acts of the New Deal began to arrive on the southern plains. It was making the Sooner state into a bunch of "leaners," as he called them. Of course, Murray had run for president by promising every American an entitlement to the four B'sâbread, butter, bacon, and beans. Patronage flowed from Alfalfa Bill outward. Now his old rival, the dandy with the tilted cigarette holder and the funny accent, was bypassing him; FDR was the face of salvation. Nearly one in five people were still unemployed, but government jobs had given four

million people a paycheck. Because there were far more willing workers than jobs, the government set a quota for each county based on population. Fueled by his customary two pots of black coffee a day, the titan from Toadsuck railed against Roosevelt and his public works projects, calling him a communist. He quit the Democratic Party in protest of the New Deal. But his power was ebbing away. He could not use the National Guard to halt government help for farmers or to keep people from building roads and bridges. The people in his state loved the new president, and the papers were full of praise for the New Deal. Murray became increasingly irritable. In one speech late in the year, while puffing on a cigar, Murray lit into the president as usual. Just then, a schoolboy raised a voice. Murray exploded, snapping at the child.

"You little screw worm!" the governor shouted at the boy. "Get out of here!" Alfalfa Bill's political career never recovered.

One proposal that Murray had championed was a plan to dam the Beaver River near Guymon, the first sizable town east of Boise City. As envisioned by promoters in No Man's Land, the dam would hold enough water to allow people to irrigate, and then they would no longer have to rely on rain. And if the Beaver ran dry, as it often did, they could mine the big aquifer that underlay the southern plains, the Ogallala, for water. So long as they put water in a pen, it didn't matter how it got there. Hydrologists were just starting to grasp the magnitude of the Ogallala: it was nearly the size of Lake Huron, nestled several hundred feet below the surface. With steam engines and windmills, nesters were barely able to reach the upper part of the aquifer. But what if big natural gas engines were put to work, sucking the water up to make the arid land green? The technology was not there yet, FDR was told. In the meantime, the plan to build a dam in No Man's Land landed with a thud in Washington. Harold Ickes, the Interior Secretary, was having second thoughts about encouraging people to stay on the land. Ickes believed it was better to give people incentive to leave. The land had been settled on the slogan of "a quarter-section and independence," and now that quarter-section could kill you and people were becoming dependent on the government. Ickes wanted

to get the land back into the public domain and move upward of half a million people out of the area. His idea was heresy to someâby peeling back manifest destiny, it was an admission that American settlement in the southern plains had been a colossal failure. By Ickes's reasoning, the High Plains could never be productive farmland again. Why delay the inevitable?

The president had his doubts about reverse homesteading. He did not want an uninhabited expanse of sifting sand in the middle of the country. Why not try and change the land itself? Roosevelt, like his fifth cousin Teddy, was an authentic conservationist from the start. As a child, he learned to love nature and was fascinated by the variety of plant life in the Hudson River Valley. When Roosevelt suggested planting a great wall of trees from the Canadian border to Texas, people derided the plan as a Soviet-style joke. If God wanted trees to grow on the Great Plains, he would have put them there himself. The wind blew too hard for saplings to take root; there was too little rain. But Roosevelt persisted: why not plant rows, and in between would be farmland protected from the wind, a "shelterbelt"?

"The forests are the lungs of our land," he said, "purifying our air and giving fresh strength to our people." The president asked the Forest Service to draw up a plan, to span the globe and see if there were tree species that could survive the hot breath of the plains in summer and the deep freezes of winter. At the same time, he asked Hugh Bennett and others to examine the larger question that Ickes had raised: whether to encourage any future farming at all, or to empty the plains before it was too late and the nation's midsection became a sandbox.

With the Kohler ranch losing the last of its green, the Cimarron River down to a feeble presence, and the other river in No Man's Land, the Beaver, dried up, the desire for water was all-consuming. Shallow wells, those of about eighty feet or less, were coming up dry, forcing nesters to carry water from neighbors' wells to their homes, or from town. The

Boise City News

ran a front-page picture of a pond the owner had created by pumping water into a basin, using a windmill for power.

"

CIMARRON COUNTY OASIS

" was the cut-line under the picture. In 1934, a simple pond in No Man's Land looked like heaven.

Fred Folkers lost his orchard, the last living thing on his ranch. It had been a struggle to keep the fruit trees alive through the previous two years, but 1934 delivered the knockout blow. In the spring, he had still carried buckets of water to the apples, peaches, and mulberries, but the garish orange sun bore down and the wind lashed away, and the drifts rose uncontrolled and buried the trees up to their necks until they gave up. Folkers was left with bare sticks poking out of the dunes.

Just to the north, the life-draining drought also killed the trees that Caroline Henderson, the college-educated farmer's wife, had nurtured.

"Our little locust grove which we cherished for so many years has become a small pile of fence posts," Caroline wrote to a friend.

The last of the grain left over from the big harvest of three years earlier was gone. Even the tumbleweeds that had kept farm animals alive were in short supply. Folkers had been one of the first nesters to salt his thistle, making it edible for cattle. Now some of his neighbors wondered: why couldn't people eat tumbleweeds as well? Ezra and Goldie Lowery, homesteaders in No Man's Land since 1906, came up with an idea to can thistles in brine. Friends asked them how they could eat such a thing, the nuisance weed of the prairie. It was as dry as cotton, as flavorless as cardboard, as prickly as cactus. Well, sure. Indeed they tasted like twigs, no debate there. But the Lowerys said these rolling thistles that the Germans had brought to the High Plains from the Russian steppe were good for you. High in iron and chlorophyll. Cimarron County declared a Russian Thistle Week, with county officials urging people who were on relief to get out to fields and help folks harvest tumbleweeds.

The Lowerys also started using a native plant for feed, the flowering yucca that clung to unplowed parts of No Man's Land. They dug up the roots, cut off the spines, and ground the tubes into food for cows. When mixed with a little cake meal, the pulverized yucca roots kept the animals alive, which in turn kept the milk and cream coming at a time when there was no money to buy groceries. But it also meant

that yuccas, one of the last plants holding down the powdered prairie gumbo, were now being yanked from the ground. With these two innovationsâcanned tumbleweeds and ground yucca rootsâthe Lowerys, a family of five, were able to feed themselves.

It had been a long fall for them. During the wheat boom, the Lowerys traded in their horse and buggy for a Model-T, added two rooms to the house, doubling the size, put up wallpaper to cover the newspaper on the inside walls, got linoleum floors, replaced the scrub board with a hand-cranked washing machine, and bought a generator, powered by the wind, which allowed the family to listen to the radio. Now their cattle were gone, shot and buried in a ditch. The orchard had died. The fields were bare, and the family was digging roots and canning tumbleweed. Why not leave?

"I'm not gonna put my family in a soup line," said Ezra Lowery. "Not me. We have food here and a roof over our heads."

The experiences of families that had fled served as cautionary tales. A neighbor, Clarence Snapp, and his wife, Ethel, had moved out of Boise City that year to Arkansas, where it was supposed to be wetter, with more opportunity. Clarence had been so poor when he married Ethel that he borrowed his mama's wedding ring; it was meant to

be temporary, he said. In Arkansas, Clarence worked in the fields, digging turnips and sweet potatoes. But he never made a dime. He was paid in his diggings, as he told his neighbors when he returned to No Man's Land.

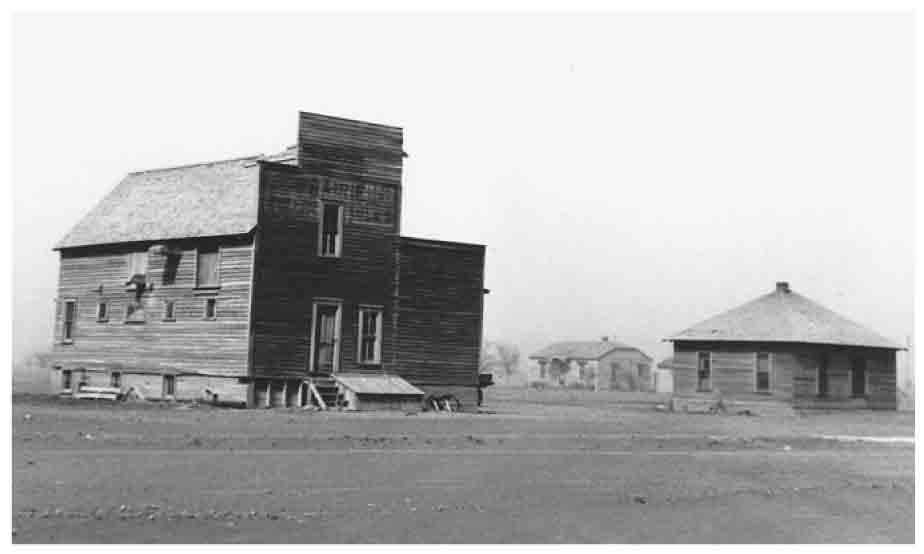

Boise City, Oklahoma, April 1936

The Ehrlichs tried grinding up thistle for cattle feed, but it did not seem to work as it did for the Lowerys; their stock herd was thinning, unable to sustain itself. Newborns came out sickly and small. For Willie Ehrlich, the only surviving boy from a family of ten, who was trying to build a life by following in his father's footsteps, the calves were his future. But he could see at birth that the animals would not live, that they looked half-formed, sickly, not ready for life. Sometimes, it made him cry to kill his calves at birth, using the blunt end of an axe to crush their heads. He was married, with two children of his own, still living with his parents on the homestead the Ehrlichs had acquired in 1900 after getting off the immigrant train. The travails of his father, George, fleeing the czar's army in Russia, surviving that typhoon at sea, and living through the cold hatred of people who thought all German Americans were suspect, gave Willie and his father enough faith they could crawl through this long hole of dirt and depression. The Ehrlichs had established themselves with a typical homesteadâ160 acres, a quarter-section big enough for cows, a garden, hogs, a few rows of oats, and some wheat. Nearly all of it was gone, reduced to a barren patch in the dun-colored air around the Texas-Oklahoma border. They lived on what they could make and store. After killing a hog, they would trim off the fat and use it for canning gel or mix it with lye to make soap. The meat was salted and rubbed with a solution of brown sugar and brine. They would let it dry for weeks, hanging from the windmill, then rub it again in salt and sugar, injecting the solution near the bones with a syringe. It would go into a bag and hang in the basement for months. They ate everything but the squeal.