The Worst Hard Time (15 page)

Read The Worst Hard Time Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

What do you want? Levi Herzstein asked Black Jack.

Everything you got.

Black Jack robbed the store of all its cash and much of its merchandise. His gang knocked off the post office next door as well. Levi Herzstein organized a posse and they chased Black Jack's gang up among the dormant volcanoes north of the Llano Estacado, and then in the draws near No Man's Land. When the posse caught up with them, Black Jack offered to surrender. As Levi Herzstein moved forward to disarm him, Black Jack pulled his pistol from his side and shot Herzstein and two Mexicans in his posse. Herzstein fell to the ground, his guts ripped open. He bled to death, as did the two other men.

It took four years for the law to catch up with Black Jack. While robbing a train, Ketchum took a shotgun blast from close range fired by a conductor. It shattered his arm, which was later amputated. He was tried for multiple crimes and sentenced to death. By popular consent, it was agreed to hang Black Jack in Clayton, New Mexico, which soon was said to have more guns per capita than any place in the Westâa safety precaution against any attempt by Black Jack's old gang to free him. It was also where Morris Herzsteinâthe surviving brotherâhad set up a new store and decided to settle down. Black Jack was scheduled to be hanged on April 26, 1901. That week, another Herzstein arrived in town, Simon, aged nineteen. He had been summoned by his uncle to come west from Philadelphia and help him build a chain of stores. Simon brought along his bride, Maude Edwards, a woman of gentile breeding and European manners who had grown up in London and Philadelphia. She was blond, very pretty, small, and

well-dressed. She spoke the crispest English heard in New Mexico Territory. When she got off the train in Clayton after crossing the empty plains and the wind-harried Llano Estacado, she found saloons doing business in the streets, the hotels full, and posters everywhere advertising the festive, upcoming execution of Black Jack Ketchum. Maude Edwards was horrified, but Simon found it fascinating. Life on the High Plains had an urgency that it did not have back in Philadelphia.

People came from hundreds of miles to see the one-armed killer hang. Newspapers from as far away as Denver, Los Angeles, and St. Louis sent correspondents. The execution was set for 1:00

P.M.

Crowds jammed around the execution site, a scaffolding built next to the jail. The sheriff gave a solemn intonation and a prayer was read. Black Jack stepped to the gallows. He was a young man still, not quite thirty-seven, with a shock of black hair, his face somewhat puffy and bloated. He looked fat, having gained more than fifty pounds in jail. The crowd quieted. A noose was put around his neck.

Any last words?

"Let her rip," Blackjack said.

The trapdoor sprang open and Ketchum fell through. But the hanging went wrong. Instead of snapping his spine behind the ear, the tightened rope caused Blackjack's head to pop off. Some said the sheriff had greased the noose so it would slide quickly and snap the neck. Others said it was the way the noose was tied. But decapitation by hanging was extremely rare, and Blackjack's case is one of only a few recorded in American execution. His hooded head broke clean and rolled around at the feet of the crowd.

Welcome to the High Plains, Morris Herzstein told Maude Edwards, late of London and Philadelphia.

Simon Herzstein never tired of telling the story about Blackjack's decapitation. It became part of the lore of the store as Simon traveled the High Plains selling fine clothes to nesters, cowpunchers, and their wives. When people would ask him what a Jew was doing peddling stiff collars in No Man's Land, he said he was doing the same as anybody else, only taking a different route. He let people buy on credit and never kept a ledger. It was all in his head. He knew they would

pay. He loved baseball, poker, and bridge. He loved throwing big dinner parties, giving Maude something to take her mind off the wind and the empty skies. And he loved the West, the freshness of it all, the Indians who came into town to trade from Navajo lands, the sons and daughters of Comancheros, who could match Simon story for story.

When the banks closed and people scrounged for food, Simon Herzstein kept up with the well-told jokes and the optimism, never letting on that he had his own troubles. As businesses folded in Dalhart, Clayton, and Boise City, the triangle of towns at the center of the High Plains, the Herzsteins fell further behind. The town of Dalhart went after Simon Herzstein, claiming in foreclosure papers that he had not paid his taxes in more than a year. Dick Coon owned the property, and he now consulted his lawyer about what to do about

the only man on the High Plains trying to keep people dressed to match their lost dignity.

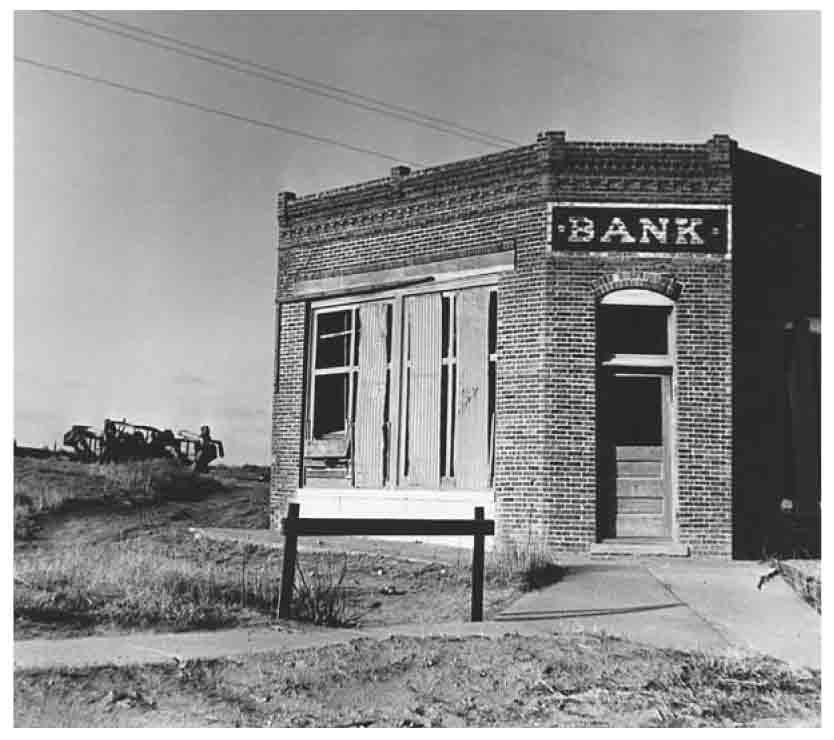

Failed bank, Kansas, 1936

As Dalhart collapsed, people in other parts of the Panhandle kept their faith, looking to the upcoming harvest of 1931 to rescue them. Sure, the First National was gone, all that money vaporized in the prairie heat, but these folks had something more lasting: they had land, and from this land came food. People

were

starving now in parts of the United States, despite what Hoover had said and despite the song that played in the background, Rudy Vallee's "Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries." American families were reduced to eating dandelions and foraging for blackberries in Arkansas, where the drought was going on two years. And over in the mountains of the Carolinas and West Virginia, a boy told the papers his family members took turns eating, each kid getting a shot at dinner every fourth night. In New York, nearly half a million people were on city relief, getting up to eight dollars a month to live on.

But here on the High Plainsâlook at this wheat in the early summer of 1931: it was pouring out of threshers, piling high once again, gold and fat, and so much of it that it formed hillocks bigger than any tuft of land in Dallam County, Texas. On the Texas Panhandle, two million acres of sod had been turned nowâa 300 percent increase over ten years ago. Up in Baca County, two hundred thousand acres. In Cimarron County, Oklahoma, another quarter million acres. The wheat came in just as the government had predictedâa record, in excess of 250 million bushels nationwide. The greatest agricultural accomplishment in the history of tilling the land, some called it. The tractors had done what no hailstorm, no blizzard, no tornado, no drought, no epic siege of frost, no prairie fire, nothing in the natural history of the southern plains had ever done. They had removed the native prairie grass, a web of perennial species evolved over twenty thousand years or more, so completely that by the end of 1931 it was a different landâthirty-three million acres stripped bare in the southern plains.

And what came from that transformed landâthe biggest crop of

all timeâwas shunned, met with the lowest price ever. The market held at nearly 50 percent below the amount it cost farmers to grow the grain. By the measure of moneyâwhich was how most people viewed success or failure on the landâthe whole experiment of trying to trick a part of the country into being something it was never meant to be was a colossal failure. Every five bushels of wheat brought in from the fields was another dollar taken out of a farmer's pocket.

The grain toasted under the hot sun. With the winds, the heat gathered strength; it chased people into their cellars all day, and it made them mean. Their throats hurt. Their skin cracked. Their eyes itched. The blast furnace was a fact of summer life, as the Great Plains historian Walter Prescott Webb said, causing rail lines to expand and warp. "A more common effect is that these hot winds render people irritable and incite nervousness," he wrote. The land hardened. Rivers that had been full in spring trickled down to a string line of water and then disappeared. That September was the warmest yet in the still-young century. Bam White scanned the sky for a "sun dog," his term for a halo that foretold of rain; he saw nothing through the heat of July, August, and September. He noticed how the horses were lethargic, trying to conserve energy. Usually, when the animals bucked or stirred, it meant a storm on the way. They had been passive for some time now, in a summer when the rains left and did not come back for nearly eight years.

W

INTER CAME WITH

a fly-by snowstorm, here and gone, and the northern winds finding the cracks of every dugout and aboveground shack holding to the hard top of No Man's Land. It came without snow up north, two years into a drought so severe that less rain fell in eastern Montana than normally fell in the desert of southern Arizona. Farmers needed the snow for insulation, the blanket that covered nubs of wheat during their dormancy in the dark months. They needed it for the first moisture of spring, a taste of water to get the wheat started again. But they got nothing from the sky. The soil turned to fine particles and started to roll, stir, and take flight. The wheat from the last two harvests on the High Plains rotted. In elevators, field mice and jackrabbits gorged themselves on it. Life was gray, flat, rudderless. There was no work in the cities. And the harder people worked in the country, the poorer they got. Wheat hit nineteen cents a bushel in some marketsâan all-time low. It perplexed farmers in No Man's Land as much as it baffled the policymakers in Washington.

"Tens of thousands of farm families have had their savings swept away and even their subsistence endangered," the Agriculture Secretary, Arthur M. Hyde, wrote the president on November 14, 1931. "Usually when weather conditions reduce production, prices rise. No such partial compensation came to the drought-stricken areas because demand and prices declined under the impact of world depression." Again, farmers begged Washington for relief. Herbert Hoover

knew about toying with the market; as the U.S. Food Administrator during the Great War, he had helped establish the first price guarantee for wheat, at two dollars a bushel, setting off a stampede of planting that would transform the grasslands. But now that all this surplus grain was rotting, he was not about to interfere with the market. Let the system cull out the losers.

Many farmers refused to surrender. The National Farmers Holiday Association urged its members to "stay at homeâbuy nothing and sell nothing," as a way to force Hoover to set a minimum price for grain. But people were already buying and selling nothing, farmers and city folk alike. It was as if all of American capitalism were held by ice in a deep winter freeze. "I feel the capitalistic system is doomed," said the head of one farmers' group.

By 1932, nearly a third of all farmers on the plains faced foreclosure for back taxes or debt; nationwide, one in twenty were losing their land. And since more Americans still worked on a farm than any other place, it meant every state was swimming in the same drowning pool. Farmers charged a courtroom in Le Mars, Iowa, demanding that a judge not sign any more foreclosure notices. He was dragged from the courthouse and taken to the empty county fairgrounds. There, a rope was strung around his neck and tied to a tree. The judge's life was spared by cooler heads. The farmers were rounded up by the Iowa National Guard and detained behind a makeshift, barbed-wire outdoor prison.

"Unless something is done for the American farmer we will have revolution in the countryside in less than twelve months," Edward O'Neal of the American Farm Bureau told Congress at the beginning of 1932. It wasn't just wheat that had sunk below the cost of producing it; milk, cattle, and hogs were all in the same depressed situation. Farmers continued to block and spill milk on the streets. If the American farmer went down, they warned in angry protests, they would take the rest of the country with them.

"The greatest emergency that ever faced this country in time of peace is confronting it now," said Congressman Wilburn Cartwright of Oklahoma.

In No Man's Land, the Folkers family learned to use their wheat

for something in every meal. They ground it for harsh breakfast cereal, sifted it to make flour for bread, blended it in a porridge with rabbit meat at dinner. Fred Folkers's life's work had become worthless, and the despair drove him to his jars of corn whiskey. He could not control the weather. And he could no longer plow any additional land; every bushel of wheat harvested led him deeper into poverty. His homestead was a quicksand of debt. The new house he had built by hand, the Model-T, the new kerosene cook stove, the piano that he and Katherine had purchased for their daughter Fayeâhe might lose it all. He would need two years, maybe three, of prices back up in the high range, a dollar or more a bushel, just to pay his debts, just to get even. Katherine was homesick and wanted to go back to Missouri again. She cried at night, dreaming of green valleys and land with trees. But Folkers said it wasn't any better in the Midwest. They had to hold on and hope that next year would be better. During the boom years, Folkers had been wise enough to put some money away. But now his savings were gone, wiped out in the banking collapse. He withdrew into a paralysis, blank-faced, skulking around the homestead and talking to his fruit orchard, the one thing that still gave him hope. At night, he sat in a chair, his fingers tapping away, going over the figures in his head. Faye never saw her father so broken.