The World's Most Dangerous Place (26 page)

Read The World's Most Dangerous Place Online

Authors: James Fergusson

We heard the story of a ‘beautiful, beautiful’ young girl brought into the clinic by her father, who couldn’t understand why his daughter kept refusing the hand of any of the many suitors he had brought her. Giama soon discovered his patient’s secret. Out of embarrassment and shame, she had told no one of the dermoid cyst growing between her legs, an object so massive that she could barely walk.

‘It is remarkable what you can find hidden beneath an abaya,’ said Giama.

FGM, he said, often led to complications like cysts, as his slideshow amply demonstrated.

There was a moment when one of our SPU men put his head round the door to check on us, and stopped dead in the shaft of light streaming in from outside, his eyes popping at another monstrous, mutilated vagina that had just flashed up on the opposite wall. Giama shooed him out and we all laughed at the guard’s comic-book confusion, although I wondered whether he had fully understood what we three men were doing, looking at such explicit pictures together in a darkened room. There was, of course, nothing erotic about the experience. Giama’s surgery was more suggestive of a butcher’s shop than a brothel; the flesh so rudely exposed in his slideshow spoke of carnage, not carnality. Certainly, one was nothing but repulsed by the close-up of a six-year-old girl who had been sewn up so tightly that there was no opening left in her vagina at all: ‘The result of a really well-done Pharaonic infibulation,’ Giama drily observed. The girl was in agony when she was brought in, suffering from ischuria, or urine retention, so acute that one of her kidneys had failed.

Giama wanted to campaign against FGM in Somalia, to publicize what he had seen in his clinic, but said he didn’t have the time. The only good news was that it was in decline in the cities, and rarest of all among the diaspora, which was a ‘positive and important’ influence on the homeland. He noted that Mohamed Farole, Puntland’s Australianized president, was one of FGM’s most vociferous critics. On the other hand, Siad Barre had also tried to eradicate it in the 1970s, and failed. The practice today, Giama reckoned, was as widespread as ever among rural communities.

The reasons were complex. Ignorance played a big part. For instance, many Somalis believe FGM to be obligatory under Islam,

when in reality there is no such requirement laid out in the Koran.

*

The underlying cause, however, was Somali society’s continuing reluctance to raise women above the status of a chattel. A woman was a possession to be treasured in the way that a nomad values a good camel, and was to be kept ‘pure’ at all costs. Giama described a 28-year-old mother he had recently seen who had been sewn up for a second time, without anaesthetic, just ten minutes after giving birth. Yet perhaps the most astonishing aspect of this brutality was that it was often not men but women themselves who perpetuated it. In her autobiography

Infidel

, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who later became a Dutch MP and a noted campaigner for the rights of Muslim women, memorably described how her traditionally minded grandmother orchestrated her own ‘cutting’, against the specific wishes of her unfortunately absent parents. At the time, Hirsi Ali was just five years old.

‘A special table was prepared in [Grandma’s] bedroom, and various aunts, known and unknown, gathered in the house . . . Grandma swung her hand from side to side and said, “Once this long

kintir

[clitoris] is removed, you and your sister will be pure.” . . . She caught hold of me and gripped my upper body . . . two other women held my legs apart. The man, who was probably an itinerant traditional circumciser from the blacksmith clan, picked up a pair of scissors . . . Then the scissors went down between my legs and the man cut off my inner labia and clitoris. I heard it, like a butcher snipping the fat off a piece of meat.’

Grandma was convinced that if left uncut, Hirsi Ali would never find a husband.

‘Imagine your daughters ten years from now,’ she tells the child’s furious mother on her return. ‘Who would marry them with a long

kintir

dangling halfway down their legs?’

This attitude seemed old-fashioned to Hirsi Ali’s parents in 1975. And yet, thirty-five years on, the preoccupation with purity remains so culturally ingrained that many Somali women still refuse even to shake hands with male strangers, particularly infidel ones. I discovered this when I was introduced to Maryam Qasim, who at the time was Somalia’s Minister for Women’s Development and Family Affairs. I offered my hand; she withdrew hers to her breast, smiling and shaking her head like someone declining a canapé at a cocktail party. Her experience of exile in Birmingham, where she had worked for years as an officer for Sure Start, a British government programme for pre-schoolers, had not Westernized her.

Pirates were frequently accused of behaving in a way that was ‘alien’ to Somali culture, particularly in relation to women. They were said to procure prostitutes from Djibouti, and rape was reportedly on the rise. But Giama’s slideshow made me think more than ever that these things were symptomatic of a wider social problem, not its cause. The pirates were certainly sexually frustrated, but in that they were no different from al-Shabaab’s foot soldiers or, indeed, young men living in any conservative Muslim society. Jay Bahadur, a Canadian reporter who spent several weeks interviewing pirates in Puntland in 2008, recorded a conversation with one of them, Momman, who said: ‘The white people we see in porn movies are always so horny. How is it that you’re not?’

7

In early 2011, the Johansen family from Denmark had been kidnapped while on a yachting holiday, and were still being held in the north of Puntland. In a development that sent a frisson around

the Western world, the pirate chief had recently offered to release four of the five Danes in exchange for the hand in marriage of the Johansens’ 13-year-old daughter, Naja.

8

The Western tabloids were duly convulsed.

*

And yet, this behaviour was not so hard to recognize. Like young men everywhere, the pirates were desperate to get laid; and big money, to some, was just another means of achieving that. According to one report, proceeds from piracy had caused the traditional bride-price to rise from $5,000 to $35,000 in just six months in 2011, and young women were said to be ‘flocking’ to marry the men with the new money.

9

‘It really affected me,’ said Anab Jama, a mother of two children. ‘I divorced my husband and I married a pirate who works in Garacad. For the first few months we had a good time, but then he began to go out with another woman after he got another ransom. Finally I asked for a divorce and came back to my parents’ home in Galkacyo.’

Was the pirates’ behaviour any surprise when some young women colluded in it in this way, while so many others did so little to emancipate themselves? The pirates did not invent the attitude that led them to treat women as sex objects. As Dr Giama’s slides showed, Somali society had been mistreating their women – and women had been mistreating each other – for a very long time before any pirates came on the scene.

I kept in touch with President Alin after I left Galkacyo, hoping to hold him to his promise to take me with him to Hobyo to report on his crackdown on the pirates. Less than a month after my visit, however, there was a surge in clan violence and kidnappings that

put off any further thought of return. A two-day battle erupted in September that left sixty-eight dead and 153 wounded. The Green Line was a warzone again, and the airport, located on supposedly neutral ground between North and South Galkacyo, was briefly shelled. President Farole insisted that his troops had been battling al-Shabaab, but was contradicted by his own terrorism adviser, General Shimbir, who noted that the dead and injured were ‘mostly from one clan’, a local Darod sub-clan called the Leelkase. As so often in Somalia, the true source of the fighting may have been a traditional dispute over water wells.

10

In any case, Alin’s political position was too precarious to allow him to leave Galkacyo for long. The cabinet’s move to Hobyo never happened. Instead, at the end of the year, the president was dragged into a power struggle with his own parliament, who voted to oust him for corruption. Alin countered by declaring the vote unconstitutional, and ordering the MPs to be dismissed for incompetence. At the time of writing, the pirates were able to move about the port as freely as they pleased; the latest foreign vessel to be hijacked, the Taiwanese fishing boat

Naham 3

captured south of the Seychelles, was being held in a harbour near by.

At a major conference on Somalia in London in February 2012 – the twentieth such meeting since 1991 – the international community ‘reiterated [our] determination to eradicate piracy, noting that the problem requires a comprehensive approach on land as well as at sea’. The foreigners also ‘recognised the need to strengthen capacity in regional states’ and ‘reiterated the importance of supporting communities to tackle the underlying causes of piracy’.

11

The words were fine, but seemed entirely empty to Abdiweli Farabadane, the commander of President Alin’s counter-piracy

militia, who in March 2012 was poised for a military campaign against the pirates of Hobyo, although without much expectation of success.

‘There are no international organizations supporting us,’ he told a reporter plaintively. ‘If we had [such support] there would be no pirates in the region. Lack of support is what causes us to be powerless.’

12

Western leaders liked to assert that a lasting solution to piracy would only be found if it was ‘driven’ by Somalis themselves. The problem was that Galmudug had lost confidence in its ability to drive anything on its own. The statelet was too frail; and until a surgeon could be found who was able and willing to excise the cancer of piracy, the patient seemed likely to continue to weaken.

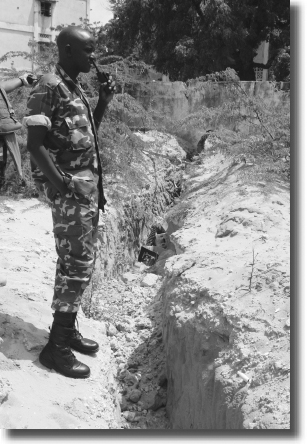

The author with Ugandan Colonel John Mugarura, of AMISOM, on the front line in Hawl Wadaag district, Mogadishu.

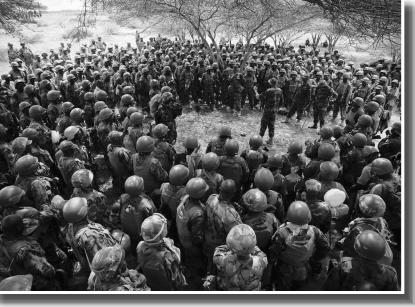

Contingency Commander Paul Lokech during an eve-of-battle briefing.

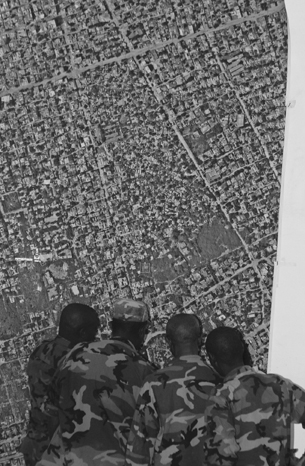

Fighting through this densely packed city required exceptional planning and leadership.