The World of Caffeine (9 page)

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

Tea’s wild popularity in China dates only from the T’ang dynasty, a golden age in China’s genuine history, when her power, influence, scope, attainments, and splendor were reminiscent of the late Roman Republic or the early Roman Empire; for as Rome had been hundreds of years earlier, the Chinese empire in its T’ang heyday was the most extensive, most populous, and richest dominion in the world. It was in this period that the Japanese, idolizing T’ang culture, adopted tea drinking as part of their efforts to emulate their neighbors. During the reign of T’ai-tsung (627–49), China extended her power over Afghanistan, Turkistan, and Tibet. Succeeding emperors brought Korea and Japan under China’s rule, and additional consolidations were effected by Empress Wu (r. 690–705), one of China’s rare women sovereigns. The T’ang government and the T’ang code of laws, resting on Confucian teachings, became models for neighboring countries. Towns grew in size and prosperity, foreign trade increased, bringing new cultural ideas and new technologies, and, in this cosmopolitan milieu, the arts flourished. A custom instituted in the seventh century under the reign of the T’ang ruler T’ai Tsung, of paying a tea tribute to the emperor, continued through the Ch’ing dynasty (1644–1911), the last imperial dynasty of China. During the T’ang dynasty, a time of luxuries and refinements, individual tea trees were celebrated for the quality of their leaf. For example, one called the “eggplant tree” grew in a gully and was watered by the seepage from a rock above. It was also during this dynasty that Chinese tea merchants commissioned Lu Yü to write a manual of tea connoisseurship,

The

Classic of Tea (Ch’a Ching).

Sometimes one man and one book can have a critical effect on an entire culture. For example, the fact that despite the existence of a generally agreed-upon normative definition of tragedy, there is in the West no corresponding account of comedy, may be traced to the fact that the part of Aristotle’s

Poetics

treating the tragic drama survived, while that treating the comic was lost. Similarly, that tea in the West has never become the central feature of culture that it is in the East may be a result of the fact that Lu Yü wrote his great book in Chinese rather than in English or French. In the year A.D. 780 the tea merchants of China hired this leading Taoist poet to produce a work extolling tea’s virtues. The result of this public relations

effort was a book dealing exhaustively and, for the most part, extremely soporifically, with every aspect of tea. After telling you more than you want to know about the cultivation, harvesting, curing, preparation, apparatus of consumption, and use of tea, Lu Yü closes with anecdotes and quotations from eminent historical figures “whose love of tea and proper conduct resulted in health, wealth, and prestige.”

14

As explained in an old preface to his work, Lu Yü has long been acknowledged as the godfather of tea authorities: “Before Lu Yü, tea was rather an ordinary thing; but in a book of only three parts, he has taught us to manufacture tea, to lay out the equipage, and to brew it properly.”

15

The earliest surviving edition of the

Ch’a

Ching

dates from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Lu Yü also authored several lost works about tea, probably drawn in even more detail, such as a book distinguishing twenty sources for water in which to boil tea leaves.

16

According to legend, Lu Yü was an orphan who was adopted by a Ch’an Bud-dhist monk of the Dragon Cloud Monastery. When he refused to take up the robe, his stepfather assigned to him the worst jobs around the monastery. Lu Yün ran away and joined a traveling circus as a clown, but the adulation of the crowd could not assuage his yearnings for wisdom and learning. He quit show business and immersed himself in the library of a wealthy patron. It was at this time that he is supposed to have begun writing the

Ch’a Ching.

To Lu Yü, tea drinking was emblematic of the harmony and mystical unity of the universe. “He invested the

Ch’a Ching

with the concept that dominated the religious thought of his age, whether Buddhist, Taoist, or Confucian: to see in the particular an expression of the universal.”

17

No aspect of tea, real, imaginary, or elaborate beyond reason, escaped Lu Yü’s attention. Among his extensive expositions of tea varieties:

Tea has a myriad of shapes. If I may speak vulgarly and rashly, tea may shrink and crinkle like a Mongol’s boots, or it may look like the dewlap of a wild ox, some sharp, some curling as the eaves of a house. It can look like a mushroom in whirling flight just as clouds do when they float out from behind a mountain peak. Its leaves can swell and leap as if they were being lightly tossed on wind-disturbed water. Others will look like clay, soft and malleable, prepared for the hand of the potter and will be as clear and pure as if filtered through wood. Still others will twist and turn like the rivulets carved out by a violent rain in newly tilled fields.

Those are the very finest of teas.

18

Here is his reasoned catalogue of waters:

On the question of what water to use, I would suggest that tea made from mountain streams is best, river water is all right, but well-water tea is quite inferior…. Water from the slow-flowing streams, the stone-lined pools or milk-pure springs is the best of mountain water. Never take tea made from water that falls in cascades, gushes from springs, rushes in a torrent, or that eddies and surges as if nature were rinsing its mouth. Over usage of all such water to make tea will lead to illnesses of the throat…. If the evil genius of a stream makes the water bubble like a fresh spring, pour it out.

19

Not only does he itemize types of tea and types of water, he even classifies stages of what we might regard as the undifferentiable chaos of boiling. The initial stage is when the water is just beginning to boil:

When the water is boiling, it must look like fishes eyes and give off but the hint of a sound. When at the edges it clatters like a bubbling spring and looks like pearls innumerable strung together, it has reached the second stage. When it leaps like breakers majestic and resounds like a swelling wave, it is at its peak. Any more and the water will be boiled out and should not be used.

The subsequent stage of boiling is described in even more elaborate and fanciful terms:

They should suggest eddying pools, twisting islets or floating duckweed at the time of the world’s creation. They should be like scudding clouds in a clear blue sky and should occasionally overlap like scales on fish. They should be like copper

cash,

green with age, churned by the rapids of a river, or dispose themselves as chrysanthemum petals would, promiscuously cast on a goblet’s stand.

20

As a result of the success of this book, Lu Yü was lionized by the emperor Te Tsung and became enormously popular throughout China. Finally he withdrew into an hermetic life, completing the circular course begun in his monastic childhood, and died in A.D. 804. His story did not quite end there, however. Lu Yü was supposed on his death to have been transfigured into Chazu, the genie of tea, and his effigy is still honored by tea dealers throughout the Orient.

To make tea into bricks or cakes, the leaves were pounded, shaped, and pressed into a mold, then hung above an open pit to dry over a hardwood or charcoal fire. When ready, the bricks were placed in baskets attached to either end of a pole for delivery to every part of the nation. In earlier times the cakes of pressed leaves were chewed, and later they were boiled with “onion, ginger, jujube fruit, orange peel, dogwood berries, or peppermint,”

21

or rice, spices, or milk.

22

After the T’ang dynasty the use of brick tea underwent a steady decline. However, throughout the eighteenth century, Chinese brick tea became the favorite of the Russians, who imported millions of tons.

In the Sung dynasty (960–1279), brick tea was largely replaced by a powdered tea that was mixed with hot water and whipped into a froth. Along with the new fashion of preparation came new names for tea varieties, such as “sparrow’s tongue,” “falcon’s talon,” and “gray eyebrows.” The Sung emperor Hui Tsung (1101–24), who widely influenced China’s culture, wrote a treatise championing powdered tea, which helped it attain preeminence. To see how seriously tea was then taken consider that a Sung poet in the Taoist tradition, possibly Li Chi Lai, declared that the three most venal sins were wasting fine tea through incompetent manipulation, false education of youth, and uninformed admiration of fine paintings.

23

When China fell under the rule of the Mongols, tea as a cultural force fell into decline. Marco Polo (1254–1324), an avid and meticulous observer of Chinese life and customs, never discusses tea drinking and mentions tea only in connection with the annual tea tribute paid to the emperor. Nevertheless, it was during this era of relative desuetude that the Chinese tea ceremony was born. It existed at least from the Yuan dynasty (1280–1368), for it is described in a 1335 edition of the

Pai-chang

Ch’ing Kuei,

a book of monastery regulations supposedly promulgated by Pai-Ch’ing (d. 814).

24

The prominence of tea returned with the reassertion of native imperial power in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). In the Ming dynasty tea was first prepared by steeping the cured leaf in a cup. Some wealthy tea drinkers placed a silver filigree disk in the cup to hold down the leaves. During this period, new methods of curing the leaf were developed, with the result that, when travelers from the West arrived, they encountered leaves fermented to varying extents, which they mistakenly thought were different species: black, green, and oolong. The “pathos of distance,” to use Nietzsche’s phrase, between the extravagant imperial family and their humble subjects is exemplified in the story of a certain rare tea, prepared only for the emperor, which grew on a distant mountain so inhospitable that it could be harvested only by provoking the rock-dwelling monkeys into angrily tearing off branches from the tea trees to hurl down upon their tormentors, who were then able to strip the leaves at their convenience.

25

The most celebrated tea of the Ming period was Fukien tea, grown in the hills of Wu I, which the Chinese believed could purify the blood and renew health. It was also during the Ming period that tea ascended to its full status as a ritual enjoyment and a spiritual refreshment that transcended the condition of ordinary comestibles, a standing that it retains to this day.

According to Okakura, the stages of tea development, as epitomized in the manner of tea preparation in each, correspond with the three great historical stages of Chinese civilization and culture:

The Cake-tea which was boiled, the Powdered-tea which was whipped, the Leaf-tea which was steeped, mark the distinct emotional impulses of the T’ang, the Sung, and the Ming dynasties of China. If we are inclined to borrow the much abused terminology of art-classification, we might designate them respectively, the Classic, the Romantic, and the Naturalistic schools of Tea.

26

Outside China, the peoples of the Orient had their own special ways of making use of the caffeine in the tea plant. In ancient Siam, steamed tea leaves were rolled into balls and consumed with salted pig fat, oil, garlic, and dried fish. The Burmese prepared

letpet,

or “pickled tea salad,” by boiling wild tea leaves, stuffing them into a hollow bamboo shoot and burying them for several months, after which they were excavated to serve as a delicacy at an important feast. Tibetans still make tea using blocks of leaves that they crumble into boiling water. Like the early Turkish preparations of coffee, this tea is heavily reboiled. Like the Galla warriors of the Ethiopian massif, who mix ground coffee beans with lard to sustain them in the harsh conditions of high altitudes, the Tibetans, who also struggle with life in a difficult environment, mix their tea with rancid yak butter, barley meal, and salt to make a nourishing breakfast treat or snack.

27

Tea, in a more highly concentrated, less exhaustively processed form than in later centuries, was one of the important and most powerful ingredients known to ancient Chinese medicine. Long before its fashionable ascension as a comestible in the T’ang dynasty, tea had joined the ranks of ginseng and certain mushrooms to which a considerable body of folklore had ascribed a marvelous range of benefits. The

Pen ts’ao kang-mu

(1578), an herbal by Li Shih-chen (1518–93), generally thought to contain material surviving from a much earlier period, illustrates the high esteem in which the leaf was held in the traditional Chinese pharmacopoeia. As Jill Anderson says, speaking of tea in China in

An Introduction to Japanese Tea Ritual

(1991), Li attributed to tea the power to

promote digestion, dissolve fats, neutralize poisons in the digestive system, cure dysentery, fight lung disease, lower fevers, and treat epilepsy. Tea was also thought to be an effective astringent for cleaning sores and recommended for washing the eyes and mouth.

28

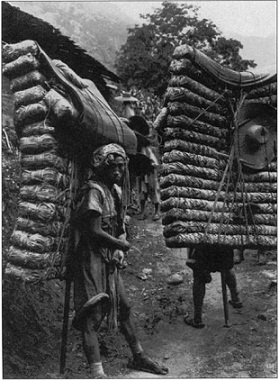

Photograph of Tibetan men carrying brick tea from China, where they had obtained it by barter. They marked about six miles a day bearing three-hundred-pound loads of the commodity, regarded as a necessity in their homeland. (Photograph by E.H.Wilson, Photographic Archives of the Arnold Arboretum, copyrighted by the President and Fellows of Harvard College, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts)