Authors: Richard Holmes

The World at War (59 page)

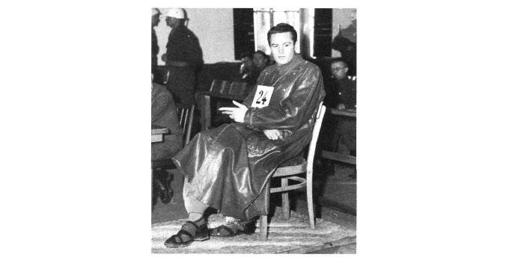

SS Lieutenant Colonel Rudolf Suttrop, Dachau Adjutant, hanged there 28 May 1946.

an hour later. Somebody must have seen us returning and must have informed on us immediately. It seemed we were surrounded by invisible evil spirits, who watched and betrayed us.

DR OTTO JOHN

Lufthansa lawyer under Klaus Bonhoeffer, older brother of German Resistance Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer

The network was gradually built up. In the beginning it was a close circle around the Bonhoeffer family with connections within Berlin and outside Berlin to university professors, to doctors all of high academic standing, liberal-minded and at heart anti-Nazi for moral more than for any other reasons. Later on they were joined by officers from all quarters, particularly conservative officers and generals of the First World War who were afraid that Hitler would lose the war. It was my job at the beginning of the war, once I had been introduced into the circle of Hans von Dohnanyi, who was the son of the Hungarian composer Erno Dohnanyi, it fell on me by chance because I had so many soldier contacts in Berlin, so I was making acquaintances here and there through trusted friends and was able to establish contacts between people who by tradition were not really friends at the beginning but in front of Hitler they got together.

*57

LIEUTENANT EWALD-HEINRICH VON KLEIST-SCHMENZIN

Surviving conspirator of the July 1944 bomb plot against Hitler

It's extremely dangerous in a dictatorship to do something against a dictatorship and it was very easy to lose your head. And most people like their own head pretty much. Furthermore, I think a person who has never lived in a dictatorship can't understand the power of propaganda. If you just hear always the same, if you read in every newspaper the same and you have very few possibilities for other information then you become very impressed by the things which you are told. And it's very difficult to have – to make up your own mind, to be critical.

DR JOHN

People in general just didn't think much. Life was easy for them, lots of work had been provided for them, exports were blossoming and they were just well-to-do people but without thinking about what was going on politically. One should also note that what the Nazis did behind the scenes was very well covered – I mean it wasn't easy at all to find out what was going on. Our group was very well informed because Hans von Dohnanyi was the Personal Assistant to the Minister of Justice and through him we had access to all information which one could possibly have in Berlin from the circle around Hitler.

HERTHA BEESE

In the flat underneath ours lived a Jewish family. The only reason they had not yet been persecuted and taken away was that the father was Italian and belonged to Mussolini's party. But when we ourselves faced more and more difficulties the wife began to feel insecure and was scared that they might take her away despite the Italian connection and she therefore left. So their flat became empty and I begged that it should not be handed over to the landlord since we still hoped there would be a total collapse and we would all be rid of our difficulties. I looked after the empty flat and one night, it must have been around midnight, the doorbell rang. I opened and there stood in front of me a Jewish couple. This was how I began to help persecuted

Jews. All of a sudden I had entered an invisible circle of people who smuggled Jews about. As soon as one hiding place had been detected they were quickly passed on. They would always move about by night. I have never found out who it was who sent them to me in the first place. Some decent people. The problems started with the feeding of the Jewish people since they neither had food-rationing cards nor very often any money. So we in turn had to make use of friends who exchanged their smoking cards for the odd potato or bread, or a friend would come and leave a bit of food. But all this was so illegal that names, sources or contacts had to remain unknown.

DR JOHN

There were friends of ours who'd been arrested and we knew their families were watched, friends of theirs were watched and the telephones were tapped. Since 1943 we were aware that the next morning the Gestapo would come. One couldn't tell how people in prison would stand up under interrogation. We expected to be arrested, all of us to be arrested, because we couldn't tell whether or not they had been tortured and had given away names. So from that time onwards we really had to be afraid of the next morning – it was said that with the milkman was coming the Gestapo.

*58

RITA BOAS-KOUPMANN

Dutch–Jewish teenager

My oldest brother, he knows a lot about politics, but my parents and the rest of the family didn't know so much. What they heard from Germany they didn't believe and they didn't like even the Jewish people coming from Germany because the things they told us were so horrible. And we didn't like them, you know why? We were not rich at all and they, they had better houses than we had, admittedly because they came to Holland with money. It sounds crazy , but we were not so very alarmed – we didn't believe all the things they said. My brother, I mean Eddie, the oldest one, came to our house in the days the war started and said, 'Come with me, let's try to escape.' And I remember my mother said, 'I must wait for the man who brings the laundry. What would you want me to escape from? I want to stay in my house and you have to do with politics, not me. What should the Germans do to me?'

PRINCE BERNHARD OF LIPPE–BIESTERFELD

Son-in-law of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands

What I remember vividly was a feeling of complete frustration because I took my wife and the children over to England and I was absolutely certain at the moment that I left that I would come back the next day. Of course we'd been fighting for three days and I took part in some of the actions in and around the palace, extraordinary enough as it may seem. I made friends with the boys that were guarding my mother-in-law and the family and I said that I'd be back tomorrow. And the next day as it happened the bombardment of Rotterdam had taken place so after my mother-in-law arrived in England I had only one feeling – I wanted to get back. I was lucky, thanks to some friends, that I managed to get back on a destroyer to Dunkirk and from Dunkirk to Zeeland and to see the rest of the fight there. Then I had to make my way back to England and after that we thought what can we do to continue, how can we start training the new people that will come from all over the world?

*59

COMMISSIONER HIEJENK

Amsterdam police officer

When the Germans crossed the bridge into Amsterdam across the Amstel there were lots of people and the most terrible thing was that among those people were a lot of them who brought up their hands in the Hitler greeting, so that you knew that they were happy for the Germans to arrive. There was nothing more terrible than to see that, to see Dutch people greeting the German troops. Another terrible thing that appeared was that several Dutch people you had trusted now turned out to be on the side of the Germans. That was the nastiest and most terrible moment that I as a policeman have experienced.

DR LOUIS DE JONG

Announcer on Radio Orange

The Netherlands government, in July 1940, was the first government-in-exile which got a broadcast programme of its own. This programme was called Radio Orange because the symbol of the Royal House of Orange was of great importance to the people in occupied Holland and so we started on 28th July 1940 with a stirring speech by Queen Wilhelmina. Conditions of broadcasting were difficult at the time not only because of the war going on, the bombing of London, but also because at first we had very little news from occupied Holland. So early in 1941 when there was a danger that we were running out of texts – the news at the time was always broadcast by the BBC European Service – we decided to start a political cabaret. I remember that we looked in all the gramophone shops in London for old Dutch records, because we used the tunes of these records and put new words to the tunes.

JETJE PAERL

Singer on Radio Orange

They had a programme every week but I wasn't in it every week. But my father wrote the songs every Saturday night and he used to listen all during the night to hear if there were any new things happening in the war that he could use, especially news that was not broadcast or was not talked about in occupied Holland. So for instance the first meeting of Churchill and Roosevelt, he wrote a song about that. And he took very often well-known songs that everybody could whistle, and made political – if you can call it that – words on it, anti-German war songs, so that the next day when people were walking in the street or cycling they could whistle this song and everybody would recognise the tune and would think, Oh, he's listened to Radio Orange too. That gave a kind of togetherness of anti-German feeling.

EDDI CHRISTIANI

Orchestra leader

The Germans give out a bulletin to everybody who was playing music, to every singer, to everybody who was actually in the business, that first of all it was forbidden to play any land of music that was composed by a Jewish composer or an American composer or a British composer. You can imagine – no music of Gershwin, no music of Cole Porter, no music of Irving Berlin and so on and so on. Even it was forbidden to play sway Dutch music and people dancing on that music. It was allowed for the Dutch people to sit down in a hall and just listen to music, but no dancing. It was also forbidden to make show with your orchestra. For instance it wasn't allowed for a trumpet player to play a muted trumpet, like Duke Ellington, or to croon. It was forbidden for a trumpet player or a saxophone player to make a movement of his instrument like swaying, it was forbidden to play a higher note than a C, a rhythm C, because it was all negro music and they say in Germany negro was the music of the devil and we are now a cultivated people, so were the Germans, so we had to play proper cultivated music. But we musicians who liked to play a good sway tune we find always a way to fool them. I can't say the Germans were a stupid people aside from that because in the past they make good music and they composed very good light music too. But we don't like the way they treated us, you know, because we are free birds and if you forbid a free bird he like to find a way to show. Just before the war we learned the song 'In the Mood' and we translate it and during the whole occupation we play 'In the Mood' and there were many Germans who believed it was a Dutch song.

RITA BOAS-KOUPMANN

I think the alarm started when Jewish people had their card with a 'J' on it. That was the first time they marked you, you had your identity card you had to carry with you and what was special was the 'J' in it and you were marked because anybody could ask for the card.

DR BRUINS SLOT

Dutch–Christian Resistance

The mistake we almost all made in Holland, apart perhaps from a few, is that we signed a declaration that we did not have any Jewish blood. You must understand we are, Holland is, a country that hasn't been at war since Napoleon. We were completely taken by surprise and psychologically we were completely broken, and perhaps you might understand the devilish system in principle but you could not see all its consequences. You must not think that all the Resistance fighters have done everything right. I don't think so at all, but it was only very slowly becoming clear.

MR VAN DER VEEN

Dutch–Christian Resistance

In November 1940 the Jewish professors of the technical university were sacked and we protested in the form of a strike. Then the university was closed and not opened until next year in April. So that was the beginning – you couldn't do your normal study programme and then you were politicised a little bit by identifying with the oppressed in the form of the Jewish professors.

B J SIJES

Dutch Resistance, Amsterdam

There were demonstrations on the birthday of Prince Bernhard at the end of June 1940. People took the opportunity to express their anti-German feeling in that way. There were demonstrations against the dismissing of Jewish civil servants and university professors. Then students went on strike in November 1940 and there are street fighting against the Dutch Nazis in summer and autumn of 1940. The economic conditions were getting worse and young workers were threatened with forced labour in Germany. And when the Germans began to terrorise the Jews living in the centre of the town, where the most poor of them were living, the Jews organised themselves in battle groups. These were the first battle groups in occupied Holland and they got help from non-Jewish workers. In another part of Amsterdam, a more wealthy part, Jews helped by non-Jews started a fight against a detachment of the Gestapo. As a reprisal the Germans arrested on Saturday and Sunday the 22nd and 23rd of February in a very brutal way more than four hundred Jews between twenty and thirty-five years. This caused immense indignation and on Monday 24 February everywhere and especially in the factories people talked of the outrage that took place in the Jewish quarter. The next day, 25th February 1941, the first anti-occupation strike in history broke out, more than one million people were involved in it.