Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (27 page)

For once Roosevelt seemed to be at a loss for words as they followed a creek meandering across a valley tucked between skyscraper rock and curtain wall. The hypnotic landscape was the promised land for anybody afflicted with even a touch of claustrophobia. Nobody has ever visited North Dakota and felt hemmed in. Like all creeks in the Badlands this one ran into the Little Missouri River. If you studied an aerial photograph, the topography looked like random lines on a hand palm or leaf veins squiggling in all directions. There was a trickling creek, it seemed, around every bend. As if living out the dream of an “old regular” or half-breed trapper, Roosevelt experienced in the Badlands the freedom to live without the shackles of the urban world. Windswept plains, unmapped wilds, the howls of hungry coyotes—all this was part of the Badlands experience for Roosevelt.

What Roosevelt had to offer Joe Ferris—and every Dakotan he rode with—was his encyclopedic knowledge of Badlands birds. A particular favorite of his were the nocturnal thrashers. Ferris was no doubt impressed that his hunting partner could identify sparrow species or melodic songsters just by tilting his ear. “One of our sweetest, loudest songsters is the meadow-lark,” Roosevelt wrote. “This I could hardly get use to at first, for it looks exactly like the eastern meadow-lark, which utters nothing but a harsh, disagreeable chatter. But the plains air seems to give it a voice, and it will perch on the top of a bush or tree and sing for hours in rich, bubbling tones.”

46

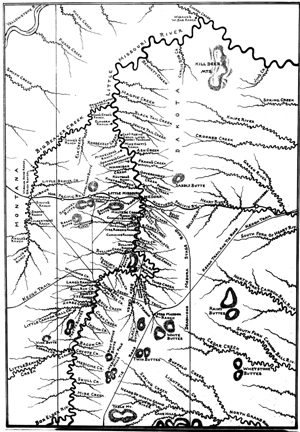

Map of the Little Missouri River in the Dakota Badlands with all its creeks and offshoots

.

Map of the Little Missouri River. (

Courtesy of T.R. Medora Foundation

)

Roosevelt and Ferris made it by dusk to their destination—a ramshackle, rat-infested cabin in a field situated at the mouth of Little Cannonball Creek. Out to greet them with extended hands were Gregor Lang and his sixteen-year-old son, Lincoln, who were operating the Neimmela Ranch for the rich London capitalist Sir John Pender.

47

According to Lincoln, Roosevelt was full of hearty cheer, saying, “Dee-lighted to meet you!” In his memoir,

Ranching with Roosevelt

, Lincoln recalled the wild-eyed “radio-active” enthusiasm of the future president. “I could make out that he was a young man, who wore large conspicuous-looking glasses, through which I was being regarded with a pair of twinkling eyes,” Lang wrote. “Amply supporting them was the expansive grin overspreading

his prominent, forceful lower face, plainly revealing a set of larger white teeth. Smiling teeth, yet withal conveying a strong suggestion of hang-and-rattle.”

48

After supper Roosevelt held court, telling the Langs his stories about the world at large. Even after the others fell asleep, Gregor, a sharp-whiskered Scotsman, and Theodore kept going at the big issues of the day, locking horns over literature and politics. This was the beginning of a lifelong friendship Roosevelt would have with the Langs. As fellow plainsmen on the prowl for buffalo during the next week, Roosevelt and his new hired friends grew closer. What Roosevelt relished about buffalo hunting, it seemed, was that social class was temporarily suspended. A man’s skill and courage were the criteria for acceptance.

The next morning, Roosevelt’s hunt party traveled together in a heavy rain, between conical buttes, anxious to find a single lonesome George or a small band of younger bulls. The soaking made it impossible to track any buffalo, and it made the Badlands clay (often called gumbo) slimy and slippery; this was very dangerous for their horses, who could easily break a leg trying to climb hillocks.

49

With creeks rising quickly and rain pounding down on their backs, Roosevelt’s party spent most of the time avoiding ooze holes and slow sand. At the rate they were going Roosevelt would have been lucky to bag a turkey vulture or common skunk. When a mule deer finally appeared, Roosevelt took aim and missed. It was an embarrassingly bad shot. Quickly Joe Ferris took a try and got his kill. Deeply impressed by the Canadian’s marksmanship, Roosevelt shouted, “By Godfrey I’d give anything in the world if I could shoot like that.”

50

That smallish deer was the high-water mark of the hunt for the first four days. Ferris hinted that it might be wise to venture back to Little Missouri and dry off for a spell; but Roosevelt insisted they grind on. Lincoln Lang was surprised at how calm Roosevelt seemed to be in the teeth of a downpour. He positively glowed in the deluge. At one point, wallowing in the flash-flood puddles, he applied mud to his face as an emollient, almost like a Lakota Sioux putting on war paint. The other men watched in shocked silence, but Lincoln dubbed him the Great White Chief.

51

Despite the unrelenting bad weather, Roosevelt continued to be entranced by his surroundings. The winds were as fierce as those along any seashore. The light—when it got a chance to break through the clouds—was often an amazing chartreuse. Like the ocean floor, much of the region was still unknown to cartographers. Every day in the Badlands he encountered some new revelatory feature of intense geological interest. Here he felt like a French-Canadian

voyageur

far away from the stresses

of civilization. This, of course, wasn’t the first time Roosevelt had succumbed to the lure of a wild place; he had similar bouts of euphoria in the Adirondacks and the North Woods. But this was somewhat different; and he began to entertain the romantic notion of becoming a Dakotan rancher. Even the clumps of box elder and prickly plants appealed to him. “Clearly I recall his wild enthusiasm over the Badlands,” Lincoln Lang later wrote. “It had taken root in the congenial soil of his consciousness, like an ineradicable, creeping plant, as it were, to thrive and permeate it thereafter, causing him more and more and more to think in the broad gauge terms of nature—of the real earth.”

52

After days of striking out the Roosevelt party caught a break. They discovered fresh spoor, and off they went in pursuit. Suddenly, there was a buffalo in sight, but upon hearing their clamor it galloped off. For several miles Roosevelt chased the bull through a rough patch of prickly shrubs and eroded gullies, to no avail. Later that afternoon, the men came across three buffalo grazing within fairly easy firing distance. Roosevelt quickly dismounted, took aim, and fired. The bullet penetrated the flesh of one, but the wounded buffalo ran off. Desperate for his big game trophy, Roosevelt chased the buffalo for seven or eight miles, only to miss with his next shot. Once again the buffalo got away. Once again Roosevelt was embarrassed.

Even though Roosevelt loved hunting, he was not a great shot; his poor eyesight prevented that. “Whatever success I have had in game-hunting,” Roosevelt later wrote, “has been due, as well as I can make it out, to three causes: first, common sense and good judgment; second, perseverance, which is the only way of allowing one to make good one’s own blunders; third the fact that I shoot as well at game as at a target. This did not make me hit difficult shots, but it prevented my missing easy shots, which a good target shot will often do in the field.”

53

What he brought to hunting was instead a bookish knowledge of the species’ habits and coloration. But Roosevelt was so excited by the windswept panoramas that he didn’t comprehend his own clumsiness with a rifle. That evening by the campfire, he remained optimistic about bagging his trophy. It was raining again the next morning when the Roosevelt party stumbled upon a couple of grazing buffalo. Theodore fired and missed his mark again. This time, at least, he could blame the weather.

The hardships Roosevelt endured in pursuit of the buffalo were many. Ants had built huge communities eight or nine feet deep. On one occasion, crawling in the sage to get closer to a bull, Roosevelt stumbled right into a cactus patch, and his hands were suddenly filled with needles as if they

were pincushions; they stayed swollen for days. When the hunt party decided to charge at a couple of buffalo, Nell got spooked and tossed its head dramatically backward, causing Roosevelt’s rifle to smack against his forehead. According to Roosevelt the blood literally “poured” into his eyes from the stitchable gash.

54

As the blood congealed, however, he spoke excitedly about the prospect of returning home with a purple scar. That evening, his face bruised, forced to sleep in the cold rain, with nothing but dry biscuit in his stomach, Roosevelt glowed with enthusiasm, refusing to engage in tremulous self-pity. It was the experience of freezing while skating at Cambridge all over again. A miserable Joe Ferris, shivering under a wet blanket, marooned in the backcountry darkness, was baffled that evening to hear Roosevelt exclaim, “By Godfrey, but this is fun!”

55

Doggedly Roosevelt kept hunting through the broken plains and pony paths along Little Cannonball Creek for his buffalo trophy. All a frustrated Joe Ferris could remember thinking was that “bad luck” was following them “like a yellow dog follows a drunkard.”

56

On the morning of September 20 Merrifield and Sylvane Ferris left the hunt for an entirely unanticipated reason: Roosevelt, in a fit of exuberance, had handed them a $14,000 check to guarantee his partnership in the Maltese Cross Ranch. Roosevelt was to become a Dakota rancher. As if they had just won the lottery, Merrifield and Sylvane were ecstatic to be trusted with an investment check and tapped to be his highly paid new managers. The two were catching a train to Minnesota to iron out all the business and banking details. Basically, by signing his name once, Roosevelt had bought the boys hundreds of new cattle on spec.

Roosevelt’s luck finally changed as, for the first time in his life, he ventured into Montana Territory, hoping to find his buffalo. Noticing that his horse was sniffing something in the air, Roosevelt dismounted, jogged up to a ridge, and peered over. There, grazing on grass, was a buffalo. “His glossy fall coat was in fine trim and shone in the rays of sun,” he later wrote, “while his pride of bearing showed him to be in the lusty vigor of his prime.” This wasn’t a lonesome George in size, but close enough. Stealthily Roosevelt advanced, one quiet foot at a time, to get within range. When he was about fifty yards away he fired a single shot. The bullet entered the buffalo’s massive shoulder. “The wound was an almost immediately fatal one,” Roosevelt wrote, “yet with surprising agility for so large and heavy an animal, he bounded up the opposite side of the ravine, heedless of two more balls, both of which went into his

flank and ranged forwards, and disappeared over the ridge at a lumbering gallop, the blood pouring from his mouth and nostrils.”

57

Sprinting ahead Roosevelt, sweating profusely, followed the blood trail until he found the buffalo “stark dead” in a ditch. All the buttes surrounding Roosevelt now took on a special glow. Hopping from foot to foot, Roosevelt encircled the buffalo, whooping and chanting as if he were White Bull or Two Moons in an effort to pay this “lordly buffalo” due reverence. A perplexed Joe Ferris had never imagined any white man behaving in such a queer fashion, imitating a Sioux or Cheyenne. An exhilarated Roosevelt, in an act of spontaneous generosity, next opened his wallet and handed Ferris $100. “I never saw any one so enthused in my life,” Ferris recalled, “and, by golly, I was enthused myself…. I was plumb tired out…I wanted to see him kill his first one as badly as he wanted to kill it.”

58

That evening the men stuffed themselves on buffalo steak, Roosevelt claiming that the meat from the hump tasted best; this was contrary to George Catlin’s promotion of buffalo tongue being the true delicacy. To Roosevelt buffalo meat was barely distinguishable from beef. The hunters didn’t sever the head or skin the carcass, however, until the following day. “The flesh of this bull tasted uncommonly good to us,” Roosevelt wrote, “for we had been without fresh meat for a week.” The

New York World

had caricatured him as a Harvard-educated aristocrat, but from now on he’d be an all-American buffalo hunter.

59

IV

When Roosevelt returned to Little Missouri on September 23, to spend another night at the Pyramid Park Hotel before heading east, he was a changed man. Francis Parkman had been right: only by living out the western experience could a scholar effectively write about it. Roosevelt’s fifteen-day growth of beard in the Dakota wilderness, and his rumble in the West, had strengthened him both mentally and physically. Now, as he slept on a cot at the Pyramid Park Hotel, he felt that he was one of the hardy trappers in the Jim Bridger vein, not Jane Dandy or Lil’ Punkin. In

Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States 1880–1917

, the historian Gail Bederman dissects Roosevelt’s obsession with becoming a “man’s man.” Pointing out how his political opponents in New York used to ridicule him as the “exquisite Mr. Roosevelt,” Bederman argues that Roosevelt’s “cowboy of the Dakotas” persona was an attempt to stamp out any traces of effeminacy. No longer would he be

publicly insulted as “given to sucking the knob of an ivory cane,” a phallic insult Roosevelt had been forced to endure, for he was now a virile buffalo hunter straight out of “Cowboy Land.”

60