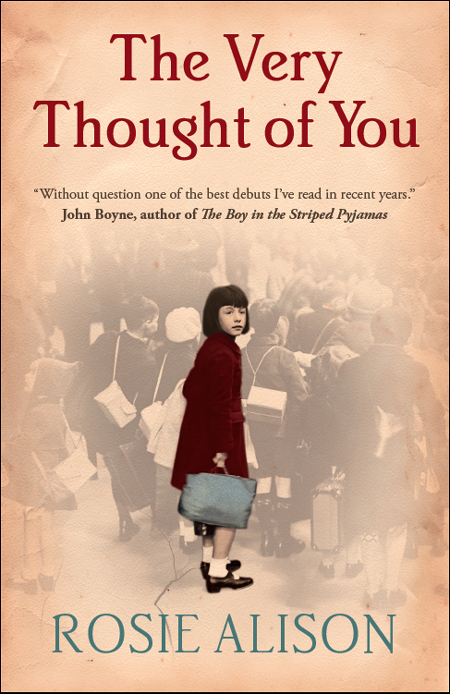

The Very Thought of You

Read The Very Thought of You Online

Authors: Rosie Alison

THE VERY THOUGHT OF YOU

ALMA BOOKS LTD

London House

243–253 Lower Mortlake Road

Richmond

Surrey TW9 2LL

United Kingdom

www.almabooks.com

First published in UK by Alma Books Limited in 2009 (Reprinted June 2009)

This mass-market edition first publshed 2010

Copyright © Rosie Alison, 2009

Epigraph: ‘Late Fragment’, from

All of Us

by Raymond Carver, published by

Harvill Press. Reprinted by permission of the Random House Group Ltd.

‘Oh, Lady Be Good’, words and music by George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin

© 1924 (Renewed) WB Music Corp. (ASCAP)

‘The Very Thought of You’, words and music by Ray Noble © 1934 Campbell

Connelly & Co Ltd. All Rights Reserved, Redwood Music Ltd (Carlin) London

NW1 8DB for the Commonwealth of Nations, Eire, South Africa and Spain

‘The Way You Look Tonight’, words by Dorothy Fields, music by Jerome

Kern © 1936 T.B. Harms & Company Incorporated, USA. Universal Music

Publishing Limited (50%). Used by Permission of Music Sales Limited and

Shapiro, Bernstein & Co., Inc. o/b/o Aldi Music.

All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured.

‘somewhere i have never travelled, gladly beyond’ is reprinted from COMPLETE

POEMS 1904-1962, by E.E. Cummings, edited by George J. Firmage, by

permission of W.W. Norton & Company. Copyright © 1991 by the Trustees for

the E.E. Cummings Trust and George James Firmage.

Rosie Alison asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this work

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either

are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any

resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events

or locales is entirely coincidental.

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Cox & Wyman Ltd, Reading, Berkshire

ISBN

: 978-1-84688-100-8

eBook ISBN

: 978-1-84688-116-9

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or

introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means

(electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the

prior written permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired

out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

THE VERY THOUGHT

OF YOU

R

OSIE

A

LISON

For my daughter Lucy

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

Raymond Carver,

Late Fragment

Contents

Back to the Old House

1946–2006

Prologue

May 1964

My dearest,

Of all the many people we meet in a lifetime, it is strange that so many of us find ourselves in thrall to one particular person. Once that face is seen, an involuntary heartache sets in for which there is no cure. All the wonder of this world finds shape in that one person, and thereafter there is no reprieve, because this kind of love does not end, or not until death—

From Baxter’s

Guide to the Historic

Houses of England

(2007)

Any visitor travelling north from York will pass through a flat vale of farmland before rising steeply onto the wide upland plateau of the North Yorkshire Moors. Here is some of the wildest and loveliest land in England, where high rolling moorland appears to reach the horizon on every side, before subsiding into voluptuous wooded valleys.

These moors are remote and empty, randomly scattered with silent sheep and half-covered tracks. It is unfenced land of many moods. In February the place is barren and lunar, prompting inward reflection. But late in August this wilderness surges into bloom, igniting a purple haze of heather which sweeps across the moors as if released to the air. This vivid wash of colour mingles with the oaks and ashes of the valleys below, where the soft limestone land flows with numerous streams and secret springs.

It is hallowed territory, graced with many medieval monasteries, all now picturesque ruins open to the sky. Rievaulx, Byland, Jervaulx, Whitby, Fountains – these are some of the better-known abbeys in these parts, and their presence testifies to the fertile promise of the land. The early monastic settlers cleared these valleys for farming, and left behind a patchwork of fields marked by many miles of drystone walls.

Nearly two centuries later, long after the monasteries had been dissolved, the Georgian gentry built several fine estates in the valleys bordering these moors. Hovingham Hall, Duncombe Park, Castle Howard and others. Trees were cleared for new

vistas, grass terraces levelled, and streams diverted into ornamental lakes – all to clarify and enhance the natural patterns of the land, as was the eighteenth-century custom.

One of the finest of these houses, if not necessarily the largest, is Ashton Park. This remote house stands on the edge of the moors, perched high above the steep Rye Valley and theatrically isolated in its wide park. For some years now, the house and its gardens have been open to the public. At one corner of an isolated village stand the ornate iron gates, and the park lodge where visitors buy their tickets. Beyond, a long white drive leads through a rising sweep of parkland, dotted with sheep and the occasional tree. It is a tranquil park, silent and still, with a wide reach of sky.

Turning to the left, the visitor sees at last the great house itself, a Palladian mansion of honeyed stone, balanced on either side with curved wings. Topping the forecourt gates are two stone figures rearing up on hind legs, a lion and a unicorn, each gazing fiercely at the other as if sworn to secrecy.

The house appears a touch doleful in its solitary grandeur, an impression which only intensifies when one enters the imposing but empty Marble Hall, with its scattering of statues on plinths. Red rope cordons mark the start of a house tour through reception rooms dressed like stage sets, leading this visitor to wonder how the house could have dwindled into quite such a counterfeit version of its past.

The guide brochure explains that when the last Ashton died, in 1979, there remained only a distant cousin in South Africa. Mrs Sandra De Groot, wife of a prominent manufacturer, appears to have been so daunted by her inheritance that she agreed to hand Ashton Park over to the National Trust in lieu of drastic death duties. But not before the estate was stripped of its remaining farmland and other valuable assets. Two Rubens paintings were sold, alongside a Claude Lorraine, a

Salvator Rosa and a pair of Constables. Soon after, her lawyers organized a sweeping sale of the house contents – a multitude of Ashton treasures accumulated over three hundred years, all recorded without sentiment in a stapled white inventory.

“One pair of carved George IV giltwood armchairs, marked; one Regency rosewood and brass-inlaid breakfast table; one nineteenth-century ormolu centrepiece…”

Antique dealers from far and wide still reminisce about the Ashton auction of 1980, the final rite of a house in decline. It is said that a queue of removal vans clogged the drive for days afterwards.

Mrs De Groot was apparently not without family feeling, because she donated a number of display cabinets to the National Trust, together with the house library and many family portraits and papers. In a curious detail, the brochure mentions that “the exquisite lacquered cigarette cases of the late Elizabeth Ashton were sent to the Victoria and Albert Museum”.

According to the notes, Ashton Park had fallen into disrepair before its reclamation. But the curators retrieved plenty of family relics and mementoes, and the walls are now hung with photographs of the Ashton sons at Eton, at Oxford, in cricket teams, in uniform. A look of permanence lingers in their faces. Downstairs are photographs of the servants, the butler and his staff all standing on the front steps, their gaze captured in that strange measure of slow time so characteristic of early cameras.

Beyond the Morning Room and past the Billiard Room, a small study displays an archive of wartime evacuees. It appears that an evacuees’ boarding school was established at Ashton Park in 1939, and a touching photograph album

reveals children of all sizes smiling in shorts and grey tunics; handwritten letters, sent in later years, describe the pleasures and sorrows of their time there.

In the last corridor there is only one photograph, an elegant wedding picture of the final Ashton heir, dated 1929. Thomas Ashton is one of those inscrutably handsome pre-war men with swept-back hair, and his wife Elizabeth is a raven-haired period beauty not unlike Vivien Leigh. Their expressions carry no hint of future losses, no sense that their house will one day become a museum.

On high days and holidays, Ashton Park attracts plenty of day trippers. An estate shop sells marmalade and trinkets, while the gardens offer picnic spots, woodland trails and dubious medieval pageants on the south lawn. And yet visitors may drive away from Ashton Park feeling faintly dejected, because the spirit of this place has somehow departed.

This melancholy cannot be traced to any dilapidation. The roof is intact, the lawns freshly mown, and the ornamental lake looks almost unnaturally limpid. But the dark windows stare out blankly – a haunted gaze. Beyond the display areas are closed corridors and unreclaimed rooms stacked with pots of paint and rusting stepladders. The small family chapel remains, but is rarely visited: it is too far out of the way to qualify for the house tour.

Perhaps it is the family’s absence which gives Ashton its pathos. It appears that there were three sons and a daughter at the start of the last century, and yet none of them produced heirs. By what cumulative misfortune did this once prosperous family reach its end? The brochure notes do not detail how or why the Ashton line died out, yet a curious visitor cannot help but wonder.

But for all this, one can still stand on the sunken lawn and almost apprehend the house in its heyday, even amidst

the signposts and litter bins. One can imagine how others – in earlier times, in the right weather – might have found in this place a peerless vision of English parkland.

There is one tree which particularly draws the eye, a glorious ruddy copper beech which stands alone on a small lawn by the rose garden. It was on a bench under this tree that the duty staff recently found an elderly woman sitting alone after closing hours, apparently enjoying the view. On closer inspection she was found to be serenely dead, her fingers locked around a faded love letter.

Evacuation

1939

1

London, 31st August 1939

There was a hint of afternoon sunshine as Anna Sands and her mother Roberta stepped off their bus into Kensington High Street. To Anna, the broad street fickered with colour as shoppers flowed past her, clutching their bags. Beyond the crowds, she could see the parade of shops tricked out with displays of every kind: tins of toffee, new-minted bowls and cups, rolls of ribbon, hats, coats and gloves from every corner of the Empire.

Mother and daughter set off down the wide pavement, Anna swinging her arms, always a little ahead. But she kept crisscrossing in front of her mother, as if uncertain whether to turn and hold her hand. For tomorrow, early, she and thousands of other children were to be evacuated from London – “In case of German air raids,” her mother had told her airily, as if this was a standard routine for all families.

“Once this crisis is over, you can come straight home again,” she had explained. Anna was looking forward to country life – or seemed to be, when asked. There were things to buy for the journey, but Anna’s impending departure hovered between them and lit every moment with unusual intimacy.