The Thief of Venice (10 page)

Read The Thief of Venice Online

Authors: Jane Langton

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General

In the Gallerie dell'Accademia a Byzantine reliquary with fragments of the True Cross is displayed beside a portrait of Cardinal Bessarion.

*20*

The more Mary went exploring with her camera, the more she was convinced that Venice was the city of Tintoretto. His paintings were everywhere, in church after church—in San Giorgio Maggiore, the Salute, the Frari—and of course in the Ducal Palace, where his

Paradise

was one of the largest paintings in the world.

She was in awe of Tintoretto. One morning, looking for a new route of exploration on her map, she found the words

Casa del Tintoretto

in the middle of Cannaregio.

She had been in this

sestiere

before. She had seen the desiccated body of Santa Lucia of Syracuse in a glass coffin like Snow White's, she had seen the Ghetto Nuovo and the Ghetto Vecchio, she had cashed a traveler's check on the Strada Nuova and stopped at a newsstand for a Paris edition of the

Herald Tribune

.

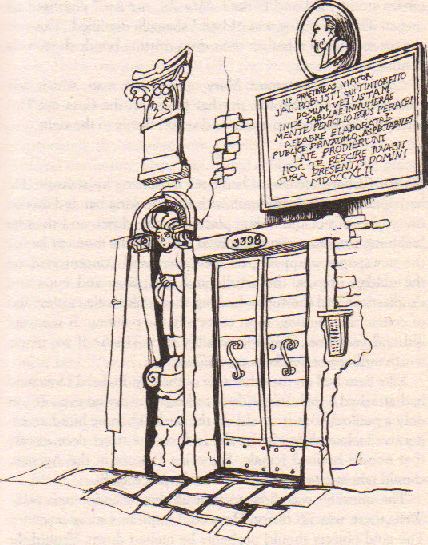

But she hadn't run across the house of Tintoretto. Everything she had read about him was admirable. Did he live in a palace? Whatever it was, she wanted to find it, to imagine the way he had lived.

It wasn't easy. Cannaregio was a maze of little wandering streets and dead ends. The canal she wanted was the Rio della Sensa. When she found it at last, she was surprised to see a gulf where the water should have been. This part of the rio had been drained. In place of the sparkling jade-green water running so pleasantly in all the other canals, there was only a muddy crevasse.

Crossing the bridge over the empty gully, she looked for the Campo dei Mori. It had to be here somewhere. Yes, of course, here it was, the Square of the Moors. One of them was set into the comer, a clumsy carved figure wearing a kind of turban. Well, fine, but where was Tintoretto's house?

Mary looked vaguely left and right, then paused to watch two families with dogs confront each other in the square. The little terrier stood rigid and barked.

"Ma dai, ma dai!"

chastised its owner. The other dog was old and shaggily dignified. The two groups moved off together, their dogs trotting beside them, tails floating high.

Come now, concentrate.

Mary opened her map, which was coming apart at the folds, put her finger on the Casa del Tintoretto, folded the map again, and set off firmly to the right.

Doctor Richard Henchard had been inspecting his treasure. He had opened up the entire wall with the wrecking bar and moved everything out of the hiding place into the closet, and then he had hung a curtain over the ruined wall. For the moment he left the newspaper-wrapped packages alone and concentrated on the golden objects, the scrolls and the plates and cups and candlesticks and the funny-looking things like little castles, and of course the painting, most especially the painting. It was very old and very fine. Could it possibly be a Titian? If so, it was worth millions of lire, billions,

trillions

.

Like Sam Bell on the other side of the city, Richard Henchard had attached a lock to the door to keep out prying eyes. It was only a padlock, but it would do the trick. Then he hired an expensive locksmith to change the lock on the street door in case that noodle-brained female, Signorina Pastora in the Agenzia, should take it into her head to rent the place again.

The question was, how to turn all this splendor into cash? Well, there was no hurry. He would explore various avenues. The gold objects should probably be melted down. Should the painting go to an art dealer in Paris? And how could he preserve anonymity? The things were absolutely, undeniably his own, but it might be necessary to produce documentary proof of legal possession. And that might be tricky, very tricky indeed.

Henchard clasped the padlock shut, pocketed the key, descended to the street, and locked the outer door. Turning away he at once caught sight of a woman with a camera. He watched as she took a picture, then another. Why didn't she stop? She was moving along the

fondamenta

, photographing every house.

Who was she? Ordinary tourists wouldn't take so many pictures. If she was just a tourist who was interested in the painter's house, why was she photographing the entire row?

Christ, now she had reached his own place—she was shooting the very window behind which his treasure was hidden. Fortunately the window was heavily curtained. Whoever had created the hiding place had nailed a blanket over the glass, a double thickness of wool. The blanket was furry with dust, like the contents of the chamber, and speckled with black strands from the crumbling ceiling, but it still kept out the light. No sunshine had entered the little room for years, and nothing could be seen from outside.

But she was still staring up at the window through the lens of her camera. Goddamn the woman! What the hell was she doing?

At last she lowered the camera. She was turning to him, looking at him.

"Permesso, signore, posso andare internamente, nella casa del Tintoretto?"

Her accent was American, not English. He moved toward her, smiling, and spoke in his native tongue. "Can one go into Tintoretto's house? I'm sorry, but it's not a museum. It's a private house."

Mary touched a button on her camera to close the shutter. Abandoning her labored Italian, she said, "I see. That's too bad."

She was a tourist then? Only a tourist? "You're visiting from America?"

"Yes." Mary smiled. "My husband and I are here for six weeks. We're teachers on sabbatical."

"Sabbatical? I see. You're on vacation." Perhaps she was not simply a tourist after all. "Oh, signora," he said, remembering a fragment of history, "perhaps you'd like to see the painter's church?"

"Tintoretto's church?" She looked pleased. Her cheeks were plump and pink. "Does it have some of his paintings?"

Henchard didn't have the faintest idea. "Oh, yes, many paintings. The Church of the Madonna dell' Orto. It's not far away. May I show it to you? "

He watched as the American woman thought it over. It was apparent that she was a virtuous woman, highly respectable and intelligent. Mentally removing her blouse and unhooking her brassiere, he could see that she was deep-breasted, a veritable goddess.

"Permit me to introduce myself," he said easily, offering up a pseudonym. "My name is Richard Visconti. I am a doctor, but this is my day off." Well, of course that was a lie. It meant he'd have to cancel an appointment, but that would be a relief anyway because the patient was a sad case, a man with a terminal carcinoma.

She had made up her mind. She was smiling broadly. "Why, yes, that's very kind of you."

He bowed, and lifted his arm in a courtly gesture.

"Andiamo!"

The space between the houses and the edge of the

fondamenta

above the muddy excavation was narrow. Henchard took Mary's arm with an air of courteous male guardianship, guiding her past a place where the paving stones had been taken up and piled at one side.

"My name is Mary Kelly," she said, glancing at him with that air of easy frankness so typical of American women.

"

Buongiorno

, Mrs. Kelly. Or is it Doctor Kelly? Instinct tells me you have a doctor's degree." She grinned and didn't deny it, and he made up his mind to ask her to lunch after the tour of the church.

Richard Henchard was an old hand at playing a fish. This one required the most delicate lure, the gentlest of tugs on the line.

Homer was in the kitchen of the apartment on the top floor of Sam Bell's house when Mary walked in. She was a little tipsy after drinking three glasses of wine in the company of Doctor Visconti.

He was eager to tell her about his afternoon in the catalog room of the Biblioteca Correr. "Mary, it was amazing. They don't have any computerized records at all, just a couple of kind librarians. Everything was on cards, good old catalog cards, and when they couldn't find the one for the book I wanted, they pulled out a shoebox from under the counter."

"A shoebox? Oh, surely not a shoebox?"

"What did you see today, my darling?"

"Well, let's see. I saw Tintoretto's house in Cannaregio, only I couldn't go in. I just saw it on the outside. And the Church of the Madonna dell'Orto. It was Tintoretto's parish church, that's why I wanted to see it."

"I see. It was another Tintoretto day, is that it? Those paintings of his really got to you."

"Oh, right, they certainly did. Oh, Homer, excuse me. I'm worn out. I've got to lie down."

Dropping onto the bed, Mary wondered why she had said nothing to Homer about having lunch with Richard Visconti. She didn't know why. She just hadn't wanted to, that was all there was to it.

*21*

The month of November began with rain. Sam held his umbrella low over his head and kept to the inland side of the Riva degli Schiavoni, away from the brimming

bordo

of the lagoon.

He had a lot on his mind. At least, thank God, the conference was over. But although his new sense of carelessness had been liberating for a while, it had stopped working. He cared too much about too many things.

There was item number one, but there was no point in thinking about that.

Item number two was the disappearance of Lucia Costanza, but there was no point in thinking about that either.

Item number three was more possible, his mission to reverse the Venetian belief in fraudulent relics, in the beseeching power of lighted candles, in the sanctimonious prayers broadcast over Radio Maria,

una voce cristiana nella tua casa

. With the help of Lucia Costanza and with the astonishing permission of Father Urbano and the cardinal patriarch, Sam was now putting the relics to the test.

So far in his investigations he had determined that the so-called pieces of the True Cross had come from several different kinds of wood. It was a gratifying discovery. But how old were they? That was important too. Sam didn't have the equipment to carbon-date the fragments, so he would have to have the permission of the cardinal patriarch to take them out of his house under guard and carry them across town to the university.

Item number four was the Marciana. Sam was ashamed of the way he'd been neglecting his duties. During the months of preparation for the conference and the exhibition, and then during the intense week of the conference itself, his ordinary work had fallen far behind. His boss, the director of the Marciana, had made a few gentle remarks, almost too courteous to be understood as complaints.

And Signora Pino kept looking at Sam in melancholy urgency with an important letter in her hand or a paper to sign or a contract for vastly expensive repairs that urgently needed his signature. This morning she reminded him of his meeting with the Piazza Council. "Oh, of course," said Sam. "Thank you. I had forgotten."

The Piazza Council was the new group of functionaries from all the major institutions in the neighborhood—the Biblioteca Marciana, the Palazzo Ducale and the Museo Correr, the office of the Soprintendenza ai Beni Artistici e Storici di Venezia, the Procuratie di San Marco, and of course the Basilica di San Marco itself.

They had begun to meet regularly in the Ducal Palace in the Hall of the Council of Ten, a fabulous chamber with a melancholy history and a painted ceiling writhing with gold moldings. This morning the regular members of the Piazza Council were joined by the mayor of Venice, representing the Venice City Council, and by employees of AMAV—the Venetian Environmental Multiservices Corporation—as well as by others from the Consorzio Venezia Nuova, a consortium of private contractors.

The deliberations of the Piazza Council were perhaps doomed from the start, because there was bad feeling between the city council and the rich and powerful Consorzio Venezia Nuova.

But the problem of high water in the piazza was a severe one, and it called for heroic efforts by somebody, somehow, and as soon as possible.

The mayor laid it out in plain words. "As you all know, the piazza is at the lowest point in Venice. It is also the busiest part of the city. The dangerous month of November is nearly here, and the lagoon is already spilling over the Molo twice a day, in spite of the fact that this is the time of neap tide. Let us not forget that the

moon

"—the mayor lowered his voice to a deep throb and looked grimly around the table—"the

moon

will be full again in only seven days."