The Real Life Downton Abbey (11 page)

Read The Real Life Downton Abbey Online

Authors: Jacky Hyams

At the dining table, guests and hosts alike must follow the correct etiquette for their manners at the table. Here are the most important Rules of the Table:

- NEVER take your seat until the lady of the house is seated.

- NEVER lounge on the table with your elbows, or tip back in your chair.

- NEVER play with your knives, forks or glasses. Cultivate repose at the table. It is an aid to digestion.

- NEVER tuck your napkin into your vest, yoke or collar. It is unfolded once and laid across the knees without a flourish. After the meal, at a restaurant or formal dinner, lay the napkin unfolded at your place. If you are a guest in the household and will remain for another meal, you may fold the napkin into its original creases.

- NEVER put the end of a spoon into your mouth; sip everything from the side of the spoon. Do this noiselessly.

- NEVER put your knife in your mouth, nor use a spoon when a fork will serve. Forks are used for eating ice cream and salad is folded or cut with the side of a fork, never with the knife. Even small vegetables like peas are eaten with a fork.

- NEVER hold your knife and fork in the air when your host is serving you afresh. Lay them on one side of the plate when you send it to the host by the servant.

- NEVER leave your spoon in a coffee or teacup. Lay it on the saucer.

- NEVER cool food by blowing on it. Wait until it becomes cool enough to eat.

- NEVER take a second helping at a large, formal dinner. You will find yourself eating alone.

- NEVER make noise with the eating implements against the china. Food must be eaten daintily, each thing by itself.

HE

C

OUNTRY

H

OUSE

O

WNER’S

R

ULES

Life for the toffs is a series of obligations, rules and social considerations. Here are five of the most important ones:

- The hosting of social events is, by custom, a priority for the aristocratic elite and their circle. Their lives revolve around wealth, privilege and politics. So drawing up guest lists for these events is a crucial part of the social networking which dominates their lives.

- The Shooting Party is a very important part of their social lives. It can last for several days. Usually, it starts with the master of the house hosting the shoot – but other activities like fishing or hunting may be involved for guests.

- The children of the family are the only members of the household who can move freely around the entire house, above and below stairs. If the mistress wishes to inspect the kitchen she arranges this via the butler.

- By custom, the children of the family live independently of their parents. They eat only one meal – luncheon – with their parents; other meals are taken in the schoolroom, sometimes with a tutor or nanny. (Very small children remain in the nursery, other than set times when they are brought down by staff to see the mistress.)

- Reputation is everything. Which means a reputation for moral fortitude is essential for the family. The master and mistress must ensure that chaperones are always present when all adult unmarried members of the family meet with the opposite sex. Failure to adhere to this reflects badly on anyone ignoring this rule, as well as on the household.

HE

H

OUSEHOLD

C

LEANING

R

ULES

Even cleaning does not escape the rules. Certain jobs are only allocated to women, others to men only: it all depends on the value or status of what is being cleaned. Dusting and polishing expensive house furniture in the public rooms, for instance, is a male-only task carried out by footmen. These servants, hired for their visual appeal, also carry coals up and down stairs to dining rooms, drawing rooms, libraries and the most spacious bedrooms. Yet the other staircases, corridors and bedrooms in the house – those less visible to the eye – are cleaned by housemaids, who have to get down and dirty on the floor, scrubbing and grate cleaning.

Expensive glass, china, silver and mirrors are cleaned by footmen, while scullery maids wash all the utensils and cooking pots in the kitchen.

So pernickety are the Edwardian toffs, however, that even the dirtiest, muckiest jobs in the house are associated with things they’d prefer to ignore, like sex and bodily functions. So the laundry maid, whose work involves washing things like soiled bedlinen or the lengths of white muslin that act as sanitary towels (disposable ones remain way ahead in the future), and the

lowest-ranking

housemaid, whose work involves cleaning out toilets or chamber pots, are seen as being ‘tainted’ by their work – yet another reason why the aristos are so keen to keep such people ‘invisible’ at all times by restricting them to their own quarters and stairways. Talk about control freaks. If only they’d known about robots…

The laundry maid has other woes, too. Traditionally, laundries are sited in the least accessible, most isolated areas of the country house, because the work itself is so labour intensive and messy. Yet because these laundries are far away from prying eyes, laundry maids are a fraction more accessible and likely to be more ‘at risk’ from male attention than the other young women. And, of course, not all big country houses have yet switched to outsourcing their laundry in the early 1900s. So a ‘follower’ might, just, be able to creep in on the laundry maid unobserved.

Could you blame her if she actually welcomes the diversion?

REAKING

T

HE

R

ULES

In a pre-Welfare State era, unemployment is equivalent to near destitution for the poorest people in society. So breaking the rules and being sacked, without any kind of reference, is disastrous: a life of crime, the workhouse, or for many young women, prostitution, are the only options.

When you consider that many young servant girls, especially in rural areas, are quite innocent in the ways of the world, this is tragically unfair: one very good reason why the rising tide of political pressure and campaigning for better rights for workers and women is beginning, albeit slowly, to make an impact in the early 1900s.

But right now, being thrown out of a poorly paid,

backbreaking

job and a life of rules and restrictions is disastrous: you are either locked into service – or out on your ear and destitute. It’s a shamefully bad deal.

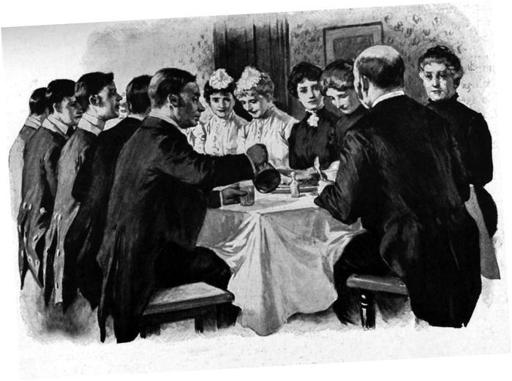

Servants sit down for dinner together in the evening.

One perfect example of the way the toffs maintain their distance from the servants is the method they use to receive messages or correspondence. When a letter arrives or a visitor leaves a calling card, only the butler or a footman can take it to the person concerned. But he cannot, at any time, merely hand it to them (even though he is wearing gloves).

CHECKING FOR HONESTYWhatever the object, it must be first placed on a small silver tray (only ever used for this purpose) and the tray is then carefully handed to the recipient. Once the person has read it, they can, if they wish, place a reply on the same tray – and hand it back to the servant.

One way either the housekeeper or the lady of the house sometimes keeps a check on the standards of work of the housemaids is to hide a series of small coins in the rooms.

If a maid takes the money and keeps it, they are promptly sacked. If, however, the coins are not mentioned at all, it means they weren’t cleaning properly so they are severely ticked off.

Chapter 5

I

t runs like clockwork from just before dawn to the wee small hours. The grand country house is a veritable hive of incessant activity on a scale similar to that seen in today’s finest luxury hotels; staff are cleaning, dusting, polishing, chopping, cooking, arranging flowers, gardening, stabling, greeting guests – the only difference between then and now is that the most pampered luxury hotel guests probably don’t expect quite the same level of personal service, someone to help them dress, undress or shave, as you would find in the big Edwardian country house.

The rules and etiquette of behaviour are rigid. Yet not all country houses are run on exactly the same lines. Nor do they have the same number of servants. Or the same number of rooms. Some owners have already installed indoor plumbing and electricity – yet still don’t permit the lower servants to use the flush toilets at night or have a bath more than once a week. Other families are more considerate of their staff ’s bodily needs. And some stubbornly insist on hanging on to the older, more

labour-intensive

ways of running the place rather than embracing the latest mod cons.

But with the family’s status and appearance so high on the priority list, one thing matters above all: any visitor here must be suitably impressed with the smooth, orderly way the house runs.

Essentially, this is a showplace, a demonstration of the family’s wealth and privilege. And that smooth running operation can only be achieved by the hard work of all the servant labour. Without the precisely calculated, hour-by-hour routine of the house, the whole thing becomes a shambles. And that must never happen…

Here is a brief rundown of a domestic schedule of the grand country house. It can, of course, vary – the family will, at set times of the year, be absent, visiting friends and family and socialising in London. And the pace of activity revs up when there are guests to be entertained with multi-course meals and shooting parties. But from the servants’ perspective, an average day’s work would run something like this…

HE

H

OUSE

The big grandfather clock in the hallway near the servants’ quarters chimes 6am.

A 14-year-old housemaid in an attic room with sloping ceilings, shared with three other young housemaids who are reluctantly waking up too, gets out of a single, narrow iron bed and steps onto the bare wooden floorboards. A small table by her bed holds the candle that lit her way up a hundred stairs to an exhausted sleep the night before. On a washstand nearby sits a china basin and a big jug. Underneath her bed is a chamber pot, which will later be collected by an odd-job man or a very young hall boy whose role it is to empty the pots, take them downstairs and tip their contents into a covered slops bucket in the outdoor area.

Padding outside in her long nightgown, down the long, chilly corridor, she reaches a servants’ bathroom. She and the other girls line up to fill their jugs with cold water, then hurry back to their room for a speedy wash, hands, face, underarms, private parts, before struggling into their underwear – knickers, pantaloons, corset – then the housemaid’s workwear, a printed dress. Downstairs in the kitchen, the scullery maid has already been up since 5am, cleaning the grates in the vast kitchen, laying out the fire to heat the kitchen range, dusting and sweeping the kitchen in readiness for Cook’s arrival, making sure everything from the night before has been cleaned.

By 6.30am

the housemaids have climbed the several flights of stairs down to the backstairs basement kitchen area, running the entire length of the house, to start their first task of the day, preparing tea and toast for the housekeeper and the lady’s maid.

Once they’ve delivered this, the housemaid’s cleaning duties begin in earnest. They are busy opening the big shutters in all the ground floor areas, dusting and polishing the furniture, tidying up from the night before, sweeping the carpets in the big dining room, morning room and drawing room. (The general idea is that many of the rooms are cleaned and tidied while the family is still sleeping so that they don’t run into the servants.)

At the same time, another housemaid is getting the fires going around the house, the coal from the coal room delivered by a footman, the wood or logs chopped the day before by the odd-job man.

7am.

Cook is in her domain and the kitchen staff, including the scullery maid, are busily getting ready for breakfast, a main meal, which involves a lot of work. One kitchen maid is designated the task of getting the servants’ breakfast ready. Supervised by Cook, all manner of dishes are being prepared for the family: eggs, sausages, kippers, kedgeree, kidneys, bread, rolls – anything and everything the family might wish to eat. It’s a busy time in the kitchen. And this is only the beginning…