The Penguin Book of First World War Stories (42 page)

Read The Penguin Book of First World War Stories Online

Authors: None,Anne-Marie Einhaus

There had been incidents down the years. They had stopped her coming for the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month by refusing her permission to sleep the night beside his grave. They said they did not have camping facilities; they affected to sympathize, but what if everybody else wanted to do the same? She replied that it was quite plain that no one else wanted to do the same but that if they did then such a desire should be respected. However, after some years she ceased to miss the official ceremony: it seemed to her full of people who remembered improperly, impurely.

There had been problems with the planting. The grass at the cemetery was French grass, and it seemed to her of the coarser type, inappropriate for British soldiers to lie beneath. Her campaign over this with the Commission led nowhere. So one spring

she took out a small spade and a square yard of English turf kept damp in a plastic bag. After dark she dug out the offending French grass and relaid the softer English turf, patting it into place, then stamping it in. She was pleased with her work, and the next year, as she approached the grave, saw no indication of her mending. But when she knelt, she realized that her work had been undone: the French grass was back again. The same had happened when she had surreptitiously planted her bulbs. Sam liked tulips, yellow ones especially, and one autumn she had pushed half a dozen bulbs into the earth. But the following spring, when she returned, there were only dusty geraniums in front of his stone.

There had also been the desecration. Not so very long ago. Arriving shortly after dawn, she found something on the grass which at first she put down to a dog. But when she saw the same in front of 1685 Private W. A. Andrade 4

th

Bn. London Regt. R. Fus. 15

th

March 1915, and in front of 675 Private Leon Emanuel Levy The Cameronians (Sco. Rif.) 16

th

August 1916 aged 21 And the Soul Returneth to God Who Gave It â Mother, she judged it most unlikely that a dog, or three dogs, had managed to find the only three Jewish graves in the cemetery. She gave the caretaker the rough edge of her tongue. He admitted that such desecration had occurred before, also that paint had been sprayed, but he always tried to arrive before anyone else and remove the signs. She told him that he might be honest but he was clearly idle. She blamed the second war. She tried not to think about it again.

For her, now, the view back to 1917 was uncluttered: the decades were mown grass, and at their end was a row of white headstones, domino-thin. 1358 Private Samuel M. Moss East Lancashire Regt. 21st January 1917, and in the middle the Star of David. Some graves in Cabaret Rouge were anonymous, with no identifying words or symbols; some had inscriptions, regimental badges, Irish harps, springboks, maple leaves, New Zealand ferns. Most had Christian crosses; only three displayed the Star of David. Private Andrade, Private Levy and Private Moss. A British soldier buried beneath the Star of David: she kept her eyes on that. Sam had written from training camp that

the fellows chaffed him, but he had always been Jewy Moss at school, and they were good fellows, most of them, as good inside the barracks as outside, anyway. They made the same remarks he'd heard before, but Jewy Moss was a British soldier, good enough to fight and die with his comrades, which is what he had done, and what he was remembered for. She pushed away the second war, which muddled things. He was a British soldier, East Lancashire Regiment, buried at Cabaret Rouge beneath the Star of David.

She wondered when they would plough them up, Herbêcourt, Devonshire, Quarry, Blighty Valley, Ulster Tower, Thistle Dump and Caterpillar Valley; Maison Blanche and Cabaret Rouge. They said they never would. This land, she read everywhere, was âthe free gift of the French people for the perpetual resting place of those of the allied armies who fellâ¦' and so on.

EVERMORE

, they said, and she wanted to hear: for all future time. The War Graves Commission, her successive members of parliament, the Foreign Office, the commanding officer of Sammy's regiment, all told her the same. She didn't believe them. Soon â in fifty years or so â everyone who had served in the War would be dead; and at some point after that, everyone who had known anyone who had served would also be dead. What if memory-grafting did not work, or the memories themselves were deemed shameful? First, she guessed, those little stone tablets in the back lanes would be chiselled out, since the French and the Germans had officially stopped hating one another years ago, and it would not do for German tourists to be accused of the cowardly assassinations perpetrated by their ancestors. Then the war memorials would come down, with their important statistics. A few might be held to have architectural interest; but some new, cheerful generation would find them morbid, and dream up better things to enliven the villages. And after that it would be time to plough up the cemeteries, to put them back to good agricultural use: they had lain fallow for too long. Priests and politicians would make it all right, and the farmers would get their land back, fertilized with blood and bone. Thiepval might become a listed building, but would they keep Brigadier Sir Frank Higginson's domed portico? That

elbow in the D

937

would be declared a traffic hazard; all it needed was a drunken casualty for the road to be made straight again after all these years. Then the great forgetting could begin, the fading into the landscape. The war would be levelled to a couple of museums, a set of demonstration trenches, and a few names, shorthand for pointless sacrifice.

Might there be one last fiery glow of remembering? In her own case, it would not be long before her annual renewals ceased, before the clerical error of her life was corrected; yet even as she pronounced herself an antique, her memories seemed to sharpen. If this happened to the individual, could it not also happen on a national scale? Might there not be, at some point in the first decades of the twenty-first century, one final moment, lit by evening sun, before the whole thing was handed over to the archivists? Might there not be a great looking-back down the mown grass of the decades, might not a gap in the trees discover the curving ranks of slender headstones, white tablets holding up to the eye their bright names and terrifying dates, their harps and springboks, maple leaves and ferns, their Christian crosses and their Stars of David? Then, in the space of a wet blink, the gap in the trees would close and the mown grass disappear, a violent indigo cloud would cover the sun, and history, gross history, daily history, would forget. Is this how it would be?

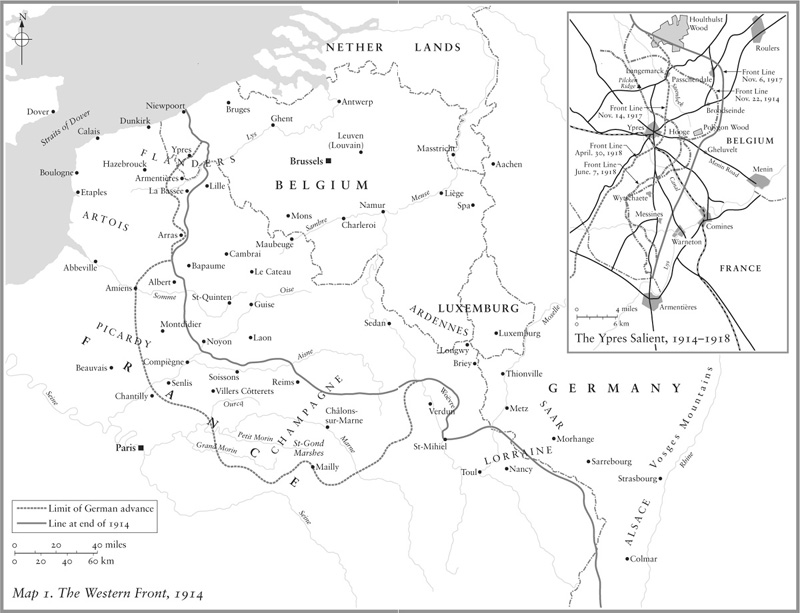

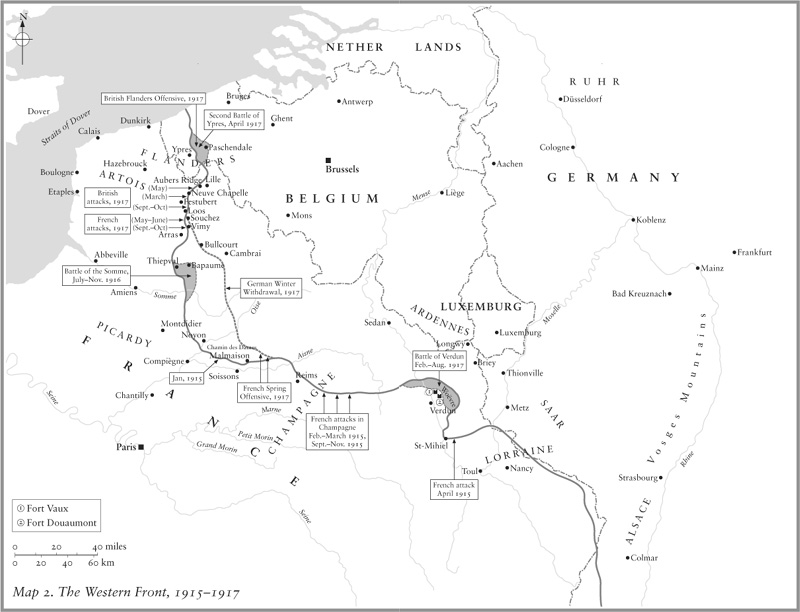

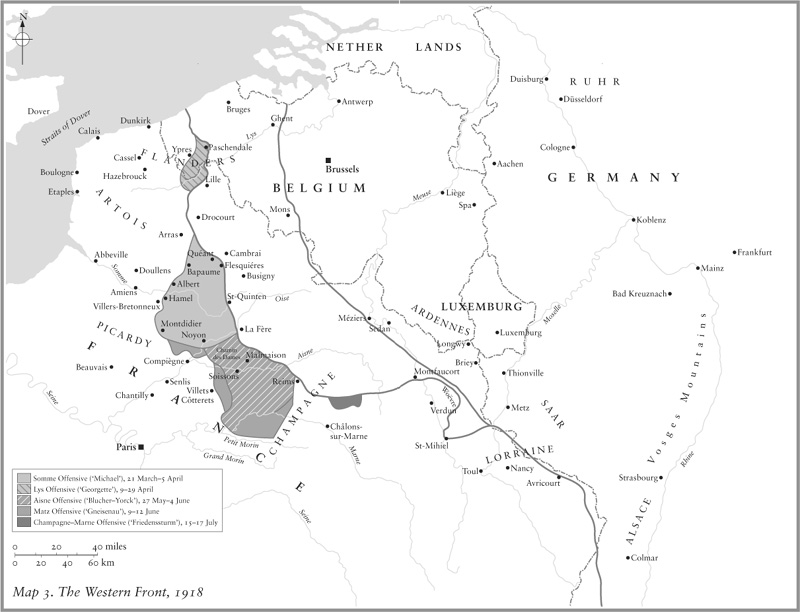

Of the many theatres of the First World War, the Western Front â that is, areas in Belgium and northern France â is the main scenario of the stories in this volume.

Mons

, the capital of the Belgian province Hainaut, was the site of the first battle of the war. It resulted in a British retreat, but stalled the German advance to the Belgian coast.

The Somme area stretches along the river Somme through northern France and Belgium.

Arras

, situated close to the front line, was largely destroyed during the war. In May 1915, Allied troops failed to break through the well-fortified German lines. Allied casualties were heavy and amounted to over 130,000 men. The offensive was renewed in June 1915, but to no avail.

Béthune

saw repeated action and was largely destroyed, as were Albert and Pêronne. The battle of the Somme was one of the major offensives of the war, a co-operation of French and British forces on a thirty-kilometre front. On the first day, 1 July 1916, almost 60,000 casualties occurred on the British side alone. The offensive was continued until 18 November 1916.

Belgian

Ypres

and the surrounding salient saw some of the most devastating battles of the war. The first battle of Ypres took place in October and November 1914, stalling the German advance to the coast at high Allied cost and resulting in the stagnation of trench warfare as both sides fortified their positions. During the second battle of Ypres (AprilâMay 1915), German troops first employed chlorine gas on a large scale, and the city of Ypres was evacuated, then almost completely destroyed. The third battle of Ypres (JulyâNovember 1917) caused the deaths of almost half a million men, many of whom drowned in the boggy marshlands surrounding the village of

Passcben

daele

. Menin Gate Memorial, opened in Ypres in July 1927, commemorates all missing British and Commonwealth soldiers of the salient. The Belgian village of

Zillebecke

, or Zillebeke, near Ypres, is the site of seventeen war cemeteries.

Verdun

was a French fortress of high symbolic value since it had long withstood the Prussians in the war of 1870â 71 and was therefore well-known to most French citizens. The German army attacked Verdun in February 1916 and succeeded in engaging the French troops in a long drawn-out siege designed to weaken the French army in other parts of the frontline.

Blighty

: Britain; coined originally by British expatriates in India, but taken up by homesick soldiers during the First World War. A âBlighty wound' required a trip home for treatment and convalescence.

Boche

: French derogatory term for Germans, used by the British during the war.

Bully

: âbully-beef', or corned beef, formed an important part of the British soldiers' rations.

Estaminet

: French tavern or public-house, frequented by locals as well as British soldiers during the war.

Fritz

: German male Christian name; used as nickname for all Germans.

Hun

: derogatory term for Germans during the war.

Jerry

: a German or German soldier.

Poilu

: nickname for French soldiers of the First World War. It derives from the adjective

poilu

, translating literally as âhairy' and referring to the unshaven faces of the soldiers, who had to spend long periods in the trenches.

Subaltern

: in the British army, a junior commissioned officer below the rank of captain.

Very lights

: flare fired by a pistol at night, either for temporary illumination, or for signalling.

Wipers

: soldiers' slang for Ypres.

Admiralty Court KC

: King's Counsel in Britain's Admiralty Court, responsible for all cases pertaining to maritime law.

ASC

: Army Signal Command.

BEF

: British Expeditionary Force â the professional army sent to France and Belgium in 1914. The term applied primarily to British soldiers stationed on the Western Front until November 1914; they were later supplemented by the volunteers of âKitchener's Army', who had been recruited and trained from August 1914 onwards. The BEF landed at Boulogne on 14 August 1914, and engaged in action at Mons and Ypres during the first months of the war.

Batt. HQ

: Battalion Headquarters.