The Opposite of Fate (8 page)

Read The Opposite of Fate Online

Authors: Amy Tan

She was also wrong in one thing about me as a writer. She believed for some reason that writing came easily to me, that words poured onto the page with the ease of turning on a faucet, and that her role was mostly to help me adjust the outpouring toward the right balance. That belief had so much to do with her confidence in me. And I guess that is the role of both an editor and a friend—to have that confidence in another person, that the person’s best is natural and always possible, forthcoming after an occasional kick in the butt.

I remember the proudest moment I had as her friend. We were at a medical clinic, and Faith was having her blood drawn. The nurse looked at Faith, then scrutinized me and said without any hint of the absurd, “You two are sisters, aren’t you?”

And Faith looked at me without any hint of the absurd and said: “Yes. Yes we are.”

If you can’t change your fate, change your attitude.

•

The Kitchen God’s Wife

To the missionaries, we were Girls of New Destiny. Each classroom had a big red banner embroidered with gold characters that proclaimed this. And every afternoon, during exercise, we sang our destiny in a song that Miss Towler had written, in both English and Chinese:

We can study, we can learn,

We can marry whom we choose.

We can work, we can earn,

And bad fate is all we lose.

•

The Bonesetter’s Daughter

I

n the last week of my mother’s life, we were all there—my three half sisters and their husbands; my younger brother, John, and his fiancée; my husband, Lou, and I—gathered around the easy chair in which she lay floating between this world and the next. She looked like a waif in an oarless boat, and we were her anchors, keeping her from leaving us too soon for the new world.

“Nyah-nyah,” she moaned in Shanghainese, and waved to an apparition on the ceiling. Then she motioned to me to invite her guests in and bring them refreshments. After I indulged my mother these wishes, I began to write her Chinese obituary, with the help of my half sisters, daughters from my mother’s first marriage. It was a task that kept our minds focused, unified us, made us feel helpful instead of helpless.

“Daisy Tan,” I started to write, “born Li Ching.”

“

Not

Li Ching,” someone interrupted. “It was Li Bingzi.” That was Yuhang speaking, my sister from Shanghai. “Li Bingzi was the name our grandmother gave her when she was born.”

How stupid of me not to know that. I had always thought

Bingzi was just a nickname my mother’s brother called her. Yuhang watched me write her important contribution to the obituary. She is sixteen years older than I, a short, ever-smiling, chubby-faced version of my mother. She speaks no English, but has read my books in translation.

“Born Li Bingzi,” I duly put down in English letters, “daughter of Li Jingmei . . .” And then Jindo, my second-eldest sister, chided in Chinese: “No, no, Grandma’s last name was not Li. Li was the father’s side. The mother’s side was Gu. Gu Jingmei.” Jindo, who most resembles our mother, proudly watched me write her addition.

By now, I sensed the ghost of my grandmother in the room. “

Ai-ya!

” she was lamenting. “What a stupid girl. This is what happens when you let them become Americans.” I imagined other wispy-edged relatives, frowning and shaking their heads.

My third-eldest sister, Lijun, picked up the baton and added to the list of corrections: “After our grandmother die,” she said in passable English, “our mother receive the name Du Lian Zen, to show she is adopt by Du family.” Lijun was the one I relied on for rough translations, her English being on a par with my Chinese, the combination of which sometimes provided hilarious if not miserable renditions of what was actually meant. Her husband, Yan Zheng, wrote “Du Lian Zen” in Chinese characters, with the English next to that in the precise block script typical of architects.

“For Ma’s school name,” Yuhang continued in Chinese, “she chose Du Ching, the same name she kept after she married Wang Zo.” I have long noted that my sisters never call this man “our father.” They knew all too well that our mother despised “that

bad man,” as she called him, and they should act as if the paternal connection were accidental at best.

“Do you know why my father renamed her Daisy?” I asked my sisters. They were eager to hear. “Well, there was a funny song about a woman named Daisy and a bicycle built for two. In it, the man asks the woman, Daisy, to marry him.”

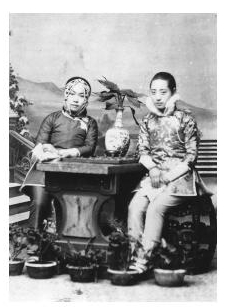

My grandmother Gu Jingmei (left) and an unidentified relative, Shanghai, circa 1905.

“So our mother liked to ride a bicycle?” Yuhang asked.

I thought about this. “No,” I answered.

“Did your father give her a bicycle when he asked to marry her?”

I laughed and shook my head. My sisters looked puzzled and confirmed among themselves that American names have no meanings.

I realized I had never told my sisters about the name Daisy Tan Chan—Chan being the name our mother took when she married for the third time, in her seventies; a year later she had the marriage annulled and reverted to Daisy C. Tan. But why bring that up now? As to her fourth “marriage,” to T. C. Lee, the dapper eighty-five-year-old gentleman whom our family in Beijing feted when he and our mother “honeymooned” in China, well, the truth was, she and T.C. never really married.

“What!” cried my sisters.

“It’s true,” I told them, to explain why I was not mentioning him in the obituary. “They were living together and she was too embarrassed to say they were lovers, so she made me lie and tell Uncle they were married.” My sisters guffawed.

My mother’s many names were vestiges of her many selves, lives I have been excavating most of my own adult life. At times I have dreaded that I might stumble across evidence of additional husbands and lovers, more secrets, more ghosts, more siblings. I had once thought I was the only daughter, the middle child, a position I took to have great psychological significance. I then discovered I was really the youngest of five girls, one of whom had died at birth. Our mother had three sons as well, one who died at age two or three, and another, my brother Peter, who died at age sixteen. With all taken into account, I was demoted to Number Seven of eight children.

There was also a great deal of confusion about my mother’s age. She had one birth date based on the Chinese lunar calendar.

By that method, she was considered one year old the day she was born. My mother had further explained to me that when my father transferred her Chinese age to a Western one, he made her

too

young—writing on her visa that she was born on May 8, 1917, instead of May 9, 1916. The age followed her into her naturalization papers, onto her Social Security card, all her official records. This was not a problem until she was about to turn sixty-four. That was when she told me she was really almost sixty-five. She insisted she knew for sure that she was older than her American age, because she was born in a Dragon Year, 1916, just as I was born in a Dragon Year thirty-six years later. There was absolutely no way she could confuse whether she was a Dragon, none whatsoever. My mother fretted over this mistake day after day, until my husband untangled bureaucratic knots and set the record straight just in time for her to retire and start collecting Social Security when she truly turned sixty-five.

But even that was not the end to her ever-changing age. My sister Jindo said that the international Chinese-language newspaper wanted to report her as being eighty-six instead of eighty-three, to account for the “bonus years” she had earned for living a long life. All the confusion about her age, her three or four marriages, her many names, and the order in which her children, living and dead, should be listed led us to nix the idea of a Chinese obituary. It simply wouldn’t look proper if we told the truth.

In trying to write an obituary, I appreciated that there was still much I did not know about my mother. Though I had written books informed by her life, she remained a source of

revelation and surprise. Of course I longed to know more about her, for her past had shaped me: her sense of danger, her regrets, the mistakes she vowed never to repeat. What I know about myself is related to what I know about her, including her secrets, or in some cases fragments of them. I found the pieces both by deliberate effort and by accident, and with each discovery I had to re-configure the growing whole.

S

he had always been tiny. When she came to the United States from China in 1949, my mother recorded that she was five feet tall, stretching the truth by at least two inches. On the day she married my father, she weighed seventy-nine pounds. When she was nine months pregnant with me, she weighed barely one hundred—even more remarkable if you consider that I came into this world at nine pounds, eleven ounces.

By age ten, I was her equal in height, and I continued to grow until I reached an impressive five feet, three and three-quarter inches. Compared with my mother, I was a giantess, and this forever skewed my perception of myself. Although my brother John and I quickly grew bigger than our mother, she had never seemed fragile to us, that is, not until she began to lose her mind.

When failure to thrive set in and she began to lose weight rapidly as well, I offered her bribes: a thousand dollars for each pound she could gain back. My mother held out her palm in gleeful anticipation. Later, I raised the stakes to ten thousand. She never collected on a single pound.

In the last week of her life, she dwindled to fifty pounds, and although I had a chronic joint problem in my shoulders, my own

pain disappeared whenever I needed to lift her from bed to chair or chair to bed. It seemed to me she was fast becoming weightless and would soon disappear.

Four years before all this, in 1995, my mother had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. She was several months shy of her eightieth birthday. The plaques on her brain had likely started to accumulate years before. But we never would have recognized the signs. “Language difficulties,” “gets into arguments,” “poor judgment”—those were traits my mother had shown her entire life. How could we distinguish between a chronically difficult personality and a dementing one?

Still, I began to look back on those times when I might have seen the clues. In 1991, when we were in Beijing, she had declined to go into one of the many temples of the Summer Palace. “Why I go see?” she said, and retreated to a cool stone bench in the shade. “Soon I just forget I been there anyway.”

My husband and I laughed. Wasn’t that the truth? Who among us could remember the blur of tourist sites we had been to in our increasing span of years?

I recalled another time, a couple of years later, when we had gathered at the home of family friends to watch a televised interview of my mother, which had been taped earlier that day. The subject was the opening of the movie

The Joy Luck Club.

The interviewer wondered whether watching the film had been difficult for her, given how much of it was true to her life: “Did you cry like everyone else in the audience?”

My mother watched her televised self as she answered in that truthful, bare-all manner of hers: “Oh, no. My real life worser than this, so movie already much, much better.” Those were my mother’s words, but they were rendered into better English

through subtitles. She was perplexed to see this. The son of our family friends called out to her, “Hey, Auntie Daisy, why are they translating what you’re saying? Don’t they know you’re speaking English?” He had the misfortune of saying this with a laughing face. My mother became livid. Forever after, she would speak about this young man, whom she had always treated like a dear nephew, with only the bitterest of criticisms about his character.

I wondered: Was her grudge toward him a sign that she was already ill? Yet my mother had always borne grudges. She never forgot a wrong, even an accidental one, but especially not an arrogant one. When her brother and sister-in-law who were visiting from Beijing told her they needed to return to China sooner than expected because of an important government meeting, my mother tried to persuade them to stay longer in California. What was more important, she cajoled, the Communist Party or family? Her sister-in-law, who had enlisted with the party in the 1930s as a young revolutionary, gave the politically correct answer. My mother was shocked to hear it. She took this to mean that her sister-in-law considered her to be worth less than a speck of dirt under the toe of her proletariat shoes. Later that day, my mother recounted to me what her sister-in-law had said. She added to that a number of slights that her sister-in-law had apparently delivered in the past week, and complaints about how, the last time she had visited them in Beijing, her sister-in-law had cut off the sleeves of an expensive shirt my mother had given to her brother, so it would be cooler. On and on my mother went, until her stream of injustices eventually did the long march through the fifty-five years of a formerly harmonious relationship.