Read The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year Online

Authors: Linda Raedisch

Tags: #Non-Fiction

The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year (4 page)

Falling midway between the ethereal Bertha and the

earthbound Anne Boleyn is the most famous White Lady of

all. For centuries, her ghost clung to a castle perched above the Vltava River which also runs through Prague. While

alive, she documented her existence so well that it is still possible to get to know her. She was born to the powerful House of Rozˇmberk (German Rosenberg) in southern

Bohemia sometime in 1429. We don’t know the exact date

of her birth, but because she was christened “Perchta,” it is tempting to think she might have been born or at least baptized during the Twelve Days of Christmas.

20 A Thousand Years of Winter

At the age of twenty, Perchta was given in wedlock to

the recently widowed Jan of Lichtenstein. The union was a

disappointment for them both. Much if not all of the con-

flict within the Lichtenstein home was precipitated by Perchta’s father’s nonpayment of the dowry. Far from helping

matters was the presence of Jan’s first wife’s mother and sister who treated the new wife like Cinderella. We know of

Perchta’s profound unhappiness from the many letters she

wrote begging her father and brothers to come and rescue

her or at least to send cash. In one of her portraits, Perchta is wearing a fine white dress but, tellingly, no jewels; she pawned the last of them in 1463 in a last ditch effort to win her husband’s affection. In 1465, she returned with her daughter to her old home at Český Krumlov Castle, her

husband having forced her to leave their one surviving son behind. She never lived with Jan again, remaining with her brother’s family until her death.

Compared to Anne Boleyn, Perchta slipped almost

soundlessly into the afterlife, dying of the plague in 1476.

Her mortal life became the palimpsest over which the story of her new career as White Lady was written, for her spirit stayed on at the old castle. Her ghost was described as a solemn lady in white holding a bunch of keys. She wore white

gloves when she had good news to impart, black gloves

when disaster loomed. Those who tried to speak to her as

she glided along the passageways were rebuffed when she

disappeared into the wall in a cloud of vapor. She was also known to make surprise inspections of the nursery, to the

horror of the nursemaids. Perchta has kept a low profile

since the death of the last Rozˇmberk, Petr Vok, in 1611,

A Thousand Years of Winter 21

though she has been credited with tearing the Nazi flag

from the castle’s tower during World War II.

Within the castle at Český Krumlov is a Baroque, long-

after-the-fact painting of Perchta in white gown and loose blue sash, her hair in golden ringlets. She holds a slender rod with which she seems to be pointing to the sweep of

arcane symbols inscribed at her feet. Whoever can decipher them, the legend says, will know where within the castle

a great treasure is hidden. If you’re going to try to decode Perchta’s message yourself, I suggest you invoke the help of that other, older Perchta before her sacred season is over.

But be careful not to spend too much time on the puz-

zle; if you are meant to solve it, you will. Don’t sit too long in the cold as Kay did on the frozen lake in the middle of the Snow Queen’s palace, arranging and re-arranging the

jagged shards of ice his mistress had given him. It was not until Gerda arrived and her tears dissolved the broken bit of mirror lodged in his heart that Kay was able, effortlessly, to spell out the word, “Eternity.” Washed out by his own

tears, the tiny, silvered glass fragment in his eye, too, fell tinkling upon the ice.

In “The Snow Queen,” the last we hear of the titular

anti-heroine is that she is going on holiday to whiten the vineyards and citron groves of the warm countries, but we

know it is only a matter of time before she circles back to her blue-lit throne room north of the Arctic Circle. Old

Perchta, too, will continue to make her rounds, carrying

both winter and Christmas to all the lands through which

she passes, for another key to long life is pride in one’s work. Perchta’s overriding mission has always been to serve

22 A Thousand Years of Winter

as a grisly embodiment of winter which can first be greeted with merry noise, then driven out again with as much, if

not more, rejoicing. “’They say she ruled for a hundred

years: a hundred years of winter,’” the Black Dwarf Nik-

abrik says admiringly of the White Witch in

Prince Caspian

.

“’There’s power, if you like. There’s something practical.’”

Craft: Distaff Tree

The word distaff means “fiber stick.” Thus, the Old Norse

dísir

and Old English

idises

, tutelary spirits who presided over the birth of a child, determined the length, thickness and overall quality of the thread which was to be that child’s life

span

, just like the fairies in “Sleeping Beauty.”

The most primitive kind of distaff is, indeed, a stick. It should be long enough that the spinner can hold it comfortably between her knees and have the cloud of unspun fibers at eye level, but not so long that she cannot tuck it under her arm if she wants to spin while walking. Any sapling or straight branch with an upward sweep of twigs on the end

will do, such as ash, sycamore or sassafras. No, you don’t need a spindle; this distaff is for decorative purposes only.

In turn-of-the-last-century Pennsylvania, the poor city

dweller’s alternative to a fresh-cut Christmas tree was a

branch of sassafras set upright in a stand, its branches covered in cotton batting. You don’t have to use sassafras for this craft, but your branch or sapling should have the same upward sweep of twigs. Strip your branch of all leaves and any loose bits of bark. Wind each twig tightly around with a strip of cotton batting or unrolled cotton ball so it looks like the tree is covered in snow. Wrap the trunk or central branch as well. When your tree is all wrapped, adorn it with

A Thousand Years of Winter 23

a short string of tiny lights. For a wintry look, I prefer clear or blue lights on a white wire. Set your creation in the window and call it a distaff, Christmas tree or queen’s scep-

ter as you like. Because the cotton has not been spun, you will have to undress the twigs before the Spinnstubenfrau

comes to inspect your work at Epiphany, but if you like, you can replace the lights on the bare twigs and keep them up

until Candlemas.

Craft: White Witch Window Star

My little origami kitchen witch who flits around the house on a toothpick broomstick began life as the point of this

star, hence the name of the following craft. To the trained eye, this star looks like a coven of eight white-cloaked

witches gathered around a blossoming bonfire. To the

untrained eye—your neighbors’, say—it’s a simple winter

decoration. Translucent paper window stars are a Christ-

mas tradition in Germany and the Netherlands. The possi-

ble folding patterns are endless.

Tools and Materials:

Scissors

Glue

2 sheets white origami paper 57⁄8 inches square, cut into

quarters

Clear tape

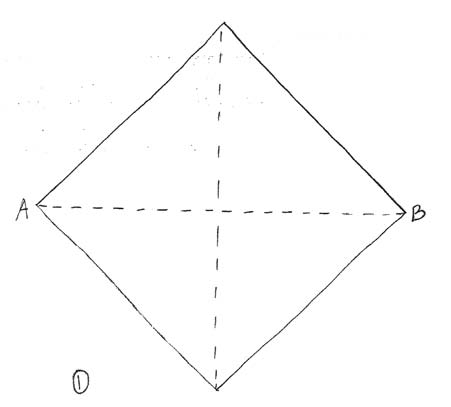

Take the first of your eight small squares of paper and fold it in half into a triangle. Fold in half again, then unfold all the way. You now have a cross to mark your center point.

(Figure 1)

24 A Thousand Years of Winter

White Witch Window Star Figure 1

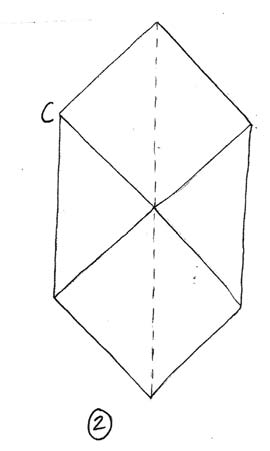

Fold points A and B in to the center point as in Figure 2.

White Witch Window Star Figure 2

A Thousand Years of Winter 25

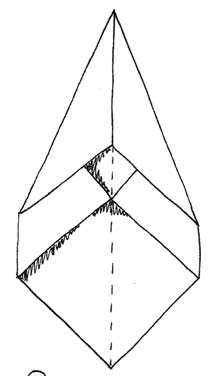

Fold points C and D in to the center line. Here is your little witch, waiting to warm her hands at the fire. (Figure 3)

White Witch Window Star Figure 3

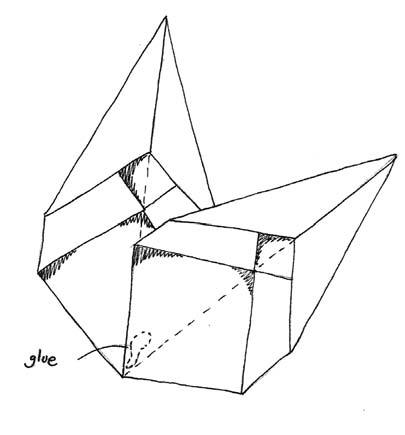

Repeat all steps with the remaining seven squares of

paper. Assemble by gluing each point (or “witch”) half-

overlapping the previous one. (Figure 4) A dab of glue is all you need.

26 A Thousand Years of Winter

White Witch Window Star Figure 4

When you have glued all the points (Figure 5), and the

glue is dry, press your star under a heavy grimoire for a day or two. Put a tiny roll of clear tape in the center of the star to stick it to the window.

A Thousand Years of Winter 27

White Witch Window Star Figure 5

At Home with the Elves

Because the world of the elves is closely bound up with

our own, it is in our own best interests to stay on the

good side of these mysterious creatures. In the old days, this might mean the pouring of milk, blood and even gifts of

gold and silver into their earthen houses. Nowadays, it can be as simple as showing kindness and respect to a stranger, because you just never know. The elves in this chapter have no interest in making toys (or becoming dentists) nor are