The Napoleon of Crime (19 page)

Read The Napoleon of Crime Online

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #Biography, #True Crime, #Non Fiction

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, painted by Gainsborough “in the bloom of youth” around 1787. “I could light my pipe at her eyes,” remarked one of the many admirers of the popular, scandal-plagued duchess.

Kitty Flynn, age twenty-three, after a photograph by French photographer Félix Nadar. This “unusually beautiful girl” became Worth’s lover and presided as hostess in his illegal Paris gambling den.

(Courtesy: Katharine Sanford)

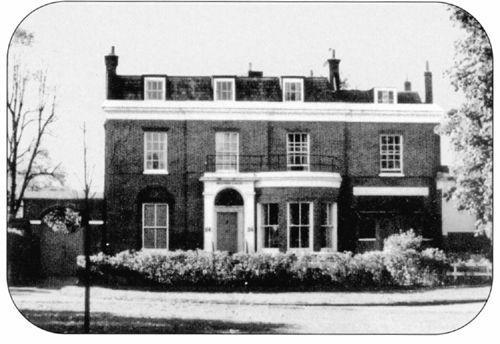

The West or Western Lodge, Worth’s London headquarters, “a commodious mansion standing well back on its own grounds out of the view of the too curious at the west corner of Clapham Common.”

The Shamrock

, Worth’s 110-foot yacht, named in honor of Kitty Flynn, his Irish lover.

THIRTEEN

My Fair Lady

W

orth’s former partners in crime, and love, Piano Charley Bullard and Kitty Flynn, had preceded him to the United States. The former was now in prison, serving time for the Boylston Bank robbery; the latter was in business, biding her time before the next social conquest. Calling herself Mrs. Kate Flynn, Kitty sought to sever contact with her former criminal associates and, as proprietor and main attraction of a men’s boarding house, had transformed herself once again, this time into a comely, impoverished, and wholly respectable New York matron. Or possibly not.

The young “widow” Flynn, according to one account, rented “

furnished rooms on the upper floors to single ‘gentlemen’ and let out her parlor rooms for card parties, small dances, lovers’ trysts and private dinners for businessmen.” Worldly and charming, Kitty soon attracted a reputation as “

an influence peddler and go-between in financial deals.” Every time a broker made a deal under her roof, Kitty got a cut. William Pinkerton considered Kitty “

dissipated” and remembered her establishment as “

a sort of semiassignation house somewheres up town.” She was, he later told his brother, “

at one time considered the mistress of a Police Magistrate in New York, I think it was Justice Ottovard.” This may be no more than idle, if intriguing, tittletattle, but it would have been entirely in character for Kitty to select a man such as Ottovard, one of the city’s powerful lawmakers, as her next lover.

After disembarking in New York, Worth immediately went to visit Kitty and the two girls, as he would repeatedly over the coming years. “

Adam told me he always went to see them when he was here, and admitted they were his daughters,” William Pinkerton later wrote. Worth was plainly still infatuated with Kitty, but he made no attempt to win her back from Justice Ottovard. The bond of conspiracy between the two former lovers, who had once shared every secret and ambition, was broken. As he sat politely sipping tea in Kitty’s parlor, Worth made no mention of the noble lady who lay faithfully at the bottom of his large trunk.

Certainly he was in a strangely euphoric mood when, on June 10, he checked into New York’s Astor House and penned a chatty letter to Messrs. Agnew & Co., brimming with impudent self-satisfaction. This was the first of ten letters sent by Worth over the next two years, all of which remain in Agnew’s archive. It must have irritated the pompous art dealer no end to be thus addressed by a man who had only recently relieved him of the world’s most expensive painting, but Worth was clearly determined to cause Agnew’s the maximum possible annoyance.

“

Gents,” he began, expansively, “A knowledge of safety has an exhilarating effect on one’s nerves after the mental strain I have just passed through, and cannot fail of being appreciated. I arrived in the SS

Saythia

on Tuesday last, bringing with me the Duchess of Devonshire.” This hail-fellow-well-met introduction was followed by some jaunty observations about the weather, his general state of well-being, and his satisfaction with the facilities at Astor House.

“Now to business,” he went on, as if bringing a friendly chin-wag to order: “This picture is worth, say, $50,000, and by this advertisement [i.e., the well-publicized theft] its value is greatly enhanced, so much so that one half that sum would be a modest sum for its return.

“Now, first, I am safe and secure from arrest. Second, this work of art is concealed. No one but MYSELF knows of it. At the same time it is perfectly safe from harm. I can get quite a sum for it here. I heard a dealer from Frisco said he’d give $10,000 if by chance it was offered for sale here, and others expressed near the same sentiment.

“Knowing this I feel under no meanness and for $25,000 I will return it undamaged. Being personally safe I am open to negotiate with any person you may send or employ—in this country, of course.

“It was a big risk, but it has the magic words: ‘There’s money in it.’

“I want no underhand work as you cannot scare me, and it is a game in which I hold the winning card. The picture is in excellent condition. Of course, I rolled it with the painted side out, so I can assure you it is in good order.”

The effect of this astonishing missive on its recipients can only be surmised, but in terms of sheer devilry, effrontery, and sly humor, it is one of Worth’s masterpieces.

As well as disguising his handwriting and adding a few persuasive illiteracies, Worth now attached a new alias, signing the letter “

Edward A. Chattrel” and giving a postal address for correspondence.

Was Worth serious about returning the painting, or was he simply playing with his victims? William Agnew had already contacted the New York picture dealer William Schaus and Robert Pinkerton, William Pinkerton’s brother and head of the detective agency’s New York office. As soon as the letter was received, detectives were sent to scour the registration books of Astor House, but naturally found that Chattrel’s name “

does not appear on the register, nor does [sic] any of the clerks or employees in the office of the hotel know him.” No postal box was registered in the name of Edward Chattrel, but a twenty-four-hour watch was placed on the post office just in case. “

Our impression, on first reading Mr. Chattrel’s note,” wrote Schaus, “was that it was a hoax, and that impression is now considerably strengthened.” Needless to say, Worth had already moved to another hotel, and never went near the post office. It seems likely that his first letter was an act of characteristic hubris, designed to baffle his pursuers and exasperate William Agnew, while notifying them who held the “winning card.”

For the moment, Worth had no intention of parting with his

Duchess

, and over the next few months he visited his old haunts, shopping for expensive clothes, dining at the best restaurants, and generally playing the part of a visiting English gentleman. By this point, it should be noted, Worth, habitual dissembler that he was, had adopted a distinctively upper-class English accent. The German-Jewish immigrant and naturalized American would remain resolutely British, in elocution and manner, for the rest of his life.

Happy to be on American soil for the first time since the Boylston job in ’69, Worth and the

Duchess

now set off on what might best be described as a triumphal tour of the country. First stop was Boston, scene of his childhood, where he visited his brother John while staying at the Adams House, which he declared to be “

the best managed hotel in the United States.” This was followed by a discreet visit to Piano Charley Bullard in Concord prison, and then on to Illinois, where Worth spent a few weeks relaxing and indulging his taste for blood sport in a resort known as Klineman’s Cabin on Lake Calumet, “

which was greatly frequented by hunters.” A few weeks later, thoroughly rested, he headed back east to Buffalo, New York, where his sister Harriet now lived with her husband.

Underworld informants had long ago told the Pinkertons of Worth’s central part in the Boylston Bank robbery, and Worth was still a wanted man in America. One night Worth was entertaining his sister and brother-in-law, a shady lawyer named Lefens, in his rooms at one of the Buffalo hotels. Midway through the party, Worth felt the need for some fresh air, but as he walked through the lobby he realized he was being watched by a man from the other side of the room. “

He felt sure it was one of our people,” William Pinkerton later recorded, after Worth had recounted the incident in detail. “His sister was upstairs and not wishing to alarm her he dodged the man, went upstairs, told his sister he was suddenly called away and [told her] to get out of the room.” Back down in the lobby, Worth tried to saunter off but the watcher spotted him and gave chase. Once outside, Worth broke into a sprint but then stopped abruptly when he caught sight of “two big policemen standing on the corner. The man made a signal to them and one reached out to grab him, knocking off his hat. They were both big stout men, as big as I am, and he started to run and as they ran after him one of them slipped and fell and the other fell over him and he got away.” The episode had unsettled him, and Worth and his

Duchess

, who had sensibly been stashed at the railway luggage office, were on the next train out of town. America was still a dangerous place, with the Pinkertons on his trail and one of the world’s most recognizable paintings in his trunk. Worth was also running low on spending money again.

For the first time Worth appears to have given serious consideration to the possibility of returning the portrait, and his next letter to Agnew’s from the United States, “

found in the letter box at Five, Waterloo Place Dec. 30. 1876,” has the unmistakable ring of urgency. The facetious, mocking tone is gone, as are the deliberate mistakes and hastily selected alias, to be replaced by a curt, almost legalistic set of demands.

December 15, 1876

Gentlemen:

We beg to inform you of the safe arrival of your picture in America, and enclose a small portion to satisfy you that we are the bona-fide holders and consequently the only parties you have to treat with. The portion we send you is cut from the upper right-hand corner looking at it from the front, which you will find matches with the remnant of the frame.

From time to time, as we negotiate with you, we will enclose pieces which will match the piece we now send you so that you can have the whole length of the frame. The picture is uninjured. There being no extradition between this country and England, we can treat with you with immunity.

This communication must be strictly confidential. If you decide to treat for the return of the picture, you must keep faith with us; as, on the first intimation we have of any police interference, we will immediately destroy the picture. You must be convinced by now of the uselessness of the police in this matter.

The picture being on this side of the water, almost any lawyer can negotiate with you without being liable to prosecution for compounding a felony. We would like to impress you with our determination which is, NO MONEY, NO PICTURE. Sooner than return, or take any great risk in returning it, we would destroy it.