The Lone Star Love Triangle: True Crime (15 page)

Read The Lone Star Love Triangle: True Crime Online

Authors: Gregg Olsen,Kathryn Casey,Rebecca Morris

Tags: #True Crime, #Retail, #Nonfiction

Considering that, the man said, “I know in my heart, if the man is completely guilty, there will be a judgment on him. I believe in Christ’s judgment.”

Another juror would later say that there were only a couple of jurors who believed Hurley might actually have been innocent, but none of them could get beyond a reasonable doubt. “My personal opinion? Yes, I think he did it,” the man said.

Looking back on the case, Speers pointed to the lack of “a smoking gun,” and said the case was circumstantial and difficult to prove.

On his way out of the courtroom, Bill Fleming’s father said, “I think the man got away with murder, but there’s nothing we can do.” Fleming’s mother walked up to Fontenot and tugged on his shoulder. The color drained from his face as she said, “I want you to know something. You did kill my son. I don’t doubt it for a solitary moment!”

DeGuerin motioned him on, and Hurley walked away.

On the courthouse steps, flanked by his brother and DeGuerin, Hurley told the gaggle of reporters: “I feel good. Real good. I’ve always been innocent, and my innocence was proved by the jury system here.”

Behind him stood the identical twins, Hurley’s one-time classmates, on this day dressed in matching yellow outfits. They waved plastic American flags over Hurley’s head as he concluded: “I’ve always been proud to be an American. But I’ve never been prouder than I am at this moment.”

As he left the courtroom, David Walker lamented the outcome and blamed the circumstance that kept much of the bad-blood evidence he’d wanted to show between Fontenot and Fleming out of the trial, because it was hearsay and inadmissible. “We couldn’t show the negative feelings because we couldn’t say what a dead man had told others,” he explained.

When asked if they would pursue any other leads, Speers said: “I believe we’ve already tried the man who killed Bill Fleming. As far as I’m concerned, the case is closed.”

SIX MONTHS AFTER THE TRIAL ENDED, a grand jury indicted Hurley’s daughter, Vanessa, charging her with perjury. DeGuerin decried the charge as sour grapes. By then Vanessa had moved to Houston, where she was an accounting major at the University of Houston. A year later, many of those who’d attended Hurley’s trial were back in the same courthouse, this time listening to taped grand jury testimony in which Vanessa said she’d never planned to fly into Houston that day and that she’d never planned to move any furniture, her father’s stated reason for borrowing the school district’s camper top. On the tape, she was also heard saying that her father never called her at 5:00 that afternoon. Hurley sat in the gallery, unemotional, listening to his daughter’s voice fill the courtroom.

“Did you know your father was involved with Laura Nugent?” the prosecutor asked Vanessa during the grand jury inquiry.

“Yes…. He told me,” she said.

“Can you tell how he felt about her?”

“He loved her,” Vanessa answered.

As at the murder trial, Vanessa’s former boss was called to the stand. He testified for a second time that he’d never walked in that office at five that day for a meeting and that the conference noted on his calendar had been held at another location. It therefore wasn’t possible that the memory of that happening spurred Vanessa to remember a phone call from her father.

When she took the stand, Vanessa called her change in recollection an honest mistake and said that she believed “in my heart” what she’d told the jurors. She also contended that investigators on the case had pressured her into the statement and hadn’t allowed her to read and correct it. “I just did what he asked me to do. He didn’t give me a choice,” she said.

When the man she referred to took the stand, Texas Ranger Tommy Walker said that he had, in fact, warned Vanessa about the possible repercussions for committing perjury: two to 10 years in prison and a fine of up to $5,000. “I was shocked by what she proposed to do. I was concerned as to the possible result.”

In the end, the irony was that while her father was found not guilty, Vanessa Fontenot was convicted and sentenced to six years probation and a $2,400 fine.

For a brief period after his daughter’s trial, Hurley Fontenot disappeared into obscurity. Unable to be an educator with the cloud of suspicion lingering, Hurley worked as a vending-machine stocker. Before long, he and Geneva again divorced, and Hurley became romantically involved with a then-42-year-old woman named Vina McCool, a desk clerk in the Livingston hotel he’d stayed in during the long weeks of the trial. Their relationship was volatile, and two years after his murder trial ended, charges were filed against Hurley for assaulting McCool. She asked that they be dropped. “What can I say? I still love that squirrelly Hurley,” she said at the time.

Then on May 17, 1989, a little more than four years after Bill Fleming’s murder, McCool was with Hurley Fontenot when he died of a massive heart attack. “He never got over the strain of that trial,” McCool said. “People still hated him and acted as if he was guilty. If he was, God will take care of it now. If not, I hope God takes care of all those people who wanted to convict him.”

WHO KILLED BILL FLEMING? Years later while working on books, my path sometimes crossed with Dick DeGuerin’s and we had lively conversations about that very topic. He still maintained that he didn’t believe Hurley was guilty, that the ex-principal with the bad heart didn’t have the physical fortitude to murder Bill Fleming and dispose of his body. “If you’re asking me if Hurley ever told me he killed Billy Mac Fleming, he never did,” DeGuerin said. “He never said anything like that to me.”

What do

I

think? I’ve always leaned toward believing that Hurley must have been the killer. I never accepted his explanation for the blood in the camper and on his truck axle: that it had somehow managed to drip off of soiled sanitary napkins and tissues. That Hurley steam-cleaned the camper and his truck the day after Fleming’s disappearance was too great a coincidence. Just think about how much blood must have been inside the camper for some to remain - enough to collect on the truck axle even after such a vigorous cleaning.

As to Hurley’s health, would the murder have been so physically taxing? Shooting a man twice through the back of the head wouldn’t take a great amount of effort. If Hurley murdered Fleming in the camper, all he had to do was drive the truck to Intercontinental Airport to pick up a parking receipt for his alibi. The next morning, he could have driven to the field and rolled the body out, then taken the truck to the car wash to steam-clean away the evidence.

The main reason I doubted Hurley’s innocence, however, was that I never believed his story that he’d stopped loving Laura Nugent. One reason is a call I received a few weeks after Hurley’s acquittal. When I picked up, the former principal said hello in his soft East Texas drawl and then added that he’d enjoyed getting to know me better at the trial.

“I just wanted to thank you,” he said.

“Why?” I asked. “What do you have to thank

me

for?”

In a whisper he answered, “You were nice to my Laura, and that means a lot.”

Photo Archive III

Laura Nugent on her parents’ front porch.

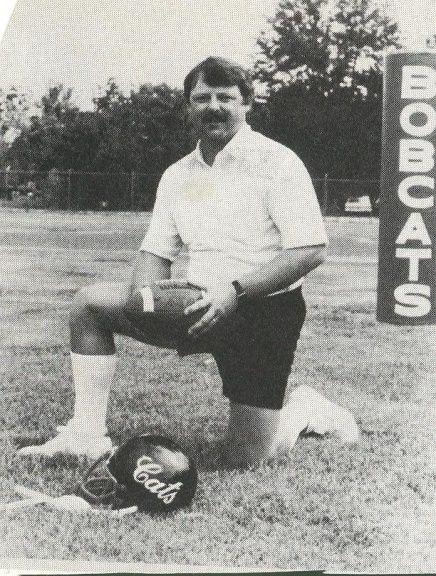

Hurley Fontenot standing outside of the junior school.

Bill Fleming.

Laura’s mother, Alma Booth.

Liberty County Sheriff E.W. “Sonny” Applebe

Author’s note:

I was at the Hurley Fontenot trial, and the remembrances of it are from my time there, talking to people and listening to testimony. It has, however, been 27 years, so I pulled some of the facts and quotes from articles in the

Houston Chronicle

, many of which were written by Cindy Horswell, who did an exceptional job covering this case. A big thank you to Janice Rubin (

www.janicerubin.com

), the superb photographer who generously allowed me to publish her pictures with this piece. – KC

Tanya Reid — The Panhandle Mother Who Loved Her Baby to Death

By Gregg Olsen

TANYA REID LOOKED AT THE GRIM FACES OF THE PEOPLE STANDING NEAR HER. Her husband. Her sister. Her parents. Her young daughter. Two detectives.

The moment she’d seen the police drive up, she knew they’d come for her.

“Tanya, you are going to have to come down to the station. We have a warrant for your arrest,” one said.

She started to cry. “Could I change my clothes and call my lawyer?” she asked.

He agreed. When she came back downstairs a few minutes later, she turned to seven-year-old Carolyn. “They’ve taken Michael away from us, and now they’re taking me away!” she cried out.

Tanya was doing what she always did, putting herself before what was best for her children, gulping the attention.