The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (9 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Brockman and his buddies knew nothing about the Holocaust as the terrible winter gave way to springtime, but he was about to learn. The lessons began slowly, as his unit, the 317th Infantry Regiment, began to run across small forced-labor camps. “We saw the camps; usually the guys ahead of us would take the camp and just clean ‘em up, getting the prisoners that was in there and trying to doctor them up. And you couldn’t feed ‘em anything, ‘cause it’d kill them. Rich food, too much rich food, was bad for ‘em.”

Somewhere ahead of Brockman and the 80th Infantry Division in the line of march to the east was Sergeant Harry Gerenstein with the 6th Armored Division. The New Yorker, now of Las Vegas, was an old man of twenty-five when he was drafted in 1942. He crossed the English Channel a month after D-Day, landed in France, and suddenly the war was real. “I saw all those ships that they sunk there, and it was a disaster. It was scary. Up until then, it didn’t mean a thing to me.”

Harry drove a truck in the division’s supply outfit. “We had no top, no doors, no windshield, and my partner had a position with .50-caliber machine gun. What they call a ring mount; it was on the truck and it goes all around, and he just stood there. I drove all through France, Luxembourg, rain or shine, we never had a top on the truck.” Like most of the other GIs, Harry knew nothing about the slave-labor camps until they discovered one.

“We liberated one place where there was a hundred twenty Hungarian Jewish women that they kept, not in a camp, but they lived in the barnyard. The Germans took off.” Harry was able to speak to the women in Yiddish. Mostly young and dressed in regular clothes, they told how they were marched into the woods every morning to a camouflaged hand grenade factory. “The women said every day they put a handful of sand in their pockets, and when they got to the factory, each one filled a hand grenade with sand instead of gunpowder. One of the women didn’t have any shoes; she wore house slippers. I had two pair of shoes, I can only wear one, so I gave her a pair of my shoes. She wanted to repay me some way. I said, ‘Forget it.’ I took a picture of them, and that was it. Then we left.”

On April 11, Gerenstein heard from his unit’s radio man that the outfit had liberated a prison camp. It was actually the first time he heard the term “concentration camp.” “We took the jeep, and that’s when I went to the camp. It was off the main roads, and we got into the camp, there were some medics there, and they called for other help. We were told, ‘Don’t feed them, don’t give them any food. The food we’re eating will kill them.’ I saw the ovens there; there was about two hundred bodies in there that the Germans never had a chance to cover them up. I went into the barracks. I don’t know if you’d call them barracks, the living quarters. I went in there, and it stunk like hell. And we stayed there not even five minutes. I couldn’t stand the odor, and we took off and went back to our outfit. I only spent about a half hour in the camp. We had to get out. We got into the jeep, and not one word was said between us. We were dumbfounded.”

Somewhere before the city of Kassel, following behind the 6th Armored, Clarence Brockman and three of his buddies from the 80th Infantry Division tired of walking, so they stole a three-quarter-ton truck from a headquarters outfit back of the line. “Changed the number and everything; wiped it off, painted it over with white camouflage paint. And then we got to Weimar, we asked the people, ‘Where’s the booze?’ You gotta have booze. But the people in the city did not have booze compared to what farmers had. So we went out to a farm. It was on a back road, the guy told us there’s two farms on that road. He says, ‘Check them out.’

“We kinda sneaked around. When you’re stalemated, that’s when you do all that.” He explained “stalemated”: “It took two regiments to take that Weimar. Well, we had three regiments that did leapfrogging, okay?” The implication is that he was in the regiment that was in reserve, and therefore a search for liquor in an appropriated vehicle was well within the bounds of off-duty activity.

“So the next day, we inquired again, and they told us about the farms. These farmers make schnapps. Powerful schnapps. And so we was drivin’ down the road to the second farmhouse, and I’d say it was about, let’s see, from Weimar to the camp was about ten kilometers. We got just a little over halfway, and I told the other guys, I says, ‘Corporal Billman,’ I says, ‘Corporal, they got monkeys over here?’ He says, ‘No.’ I said, ‘Well, what’s them up in the trees ahead of us?’ And he says, ‘Oh, they’re civilians.’ Whatever they had on, their outfits were blacker than … it was dirty.”

Brockman says the trees were a little bigger than scrub oaks. “And they was up there where you could grab ahold of the branch. So they was up in there, and there was about ten or fifteen of ‘em in different trees.

“We called ‘em down, and of course with our broken German and their broken English, we got along pretty good. There’s quite a few of them who talked English. They didn’t look like people. They was, at the end—emaciated and everything else. They had all kinds of disease.”

Brockman had no idea how the prisoners had found the strength to climb the trees, let alone to stay alive all that time. “To answer that question is to know what man’s like. But they went up there, we saw them. And they explained what was ahead of us. They told us the guards had left. The camp was already empty of German guards three days before.

“We took ‘em down there to the gates. The gates were open. And [the inmates] started rushing us. I said, ‘Whoa. We can’t go in that camp whatsoever.’ So we beat it back to Weimar, got ahold of Captain Root, which is our CIC [Counter Intelligence Corps] officer. We never went back to the camp.”

But Brockman did see former prisoners again, in both striped and black outfits, a day or two later, in Weimar, where his unit was billeted. They were tearing up the city, looting it under the watchful, even protective eyes of American troops. “We were in apartment buildings there in Weimar, fairly decent apartment buildings—they hadn’t been touched by the war. And [the former inmates] come down the street and they started shoving people aside, actually making them get off the walk and walk in the road. And some Germans resented that, and they started fightin’ them back, and then that’s when we stepped in. Usually we’d fire a shot in the air, and that’d settle it. Everybody’d be calm. It seems strange, though. The Germans would not run. You fired that shot in the air. But those poor PWs, when they’d hear a shot, boy, they’d scram. Because they didn’t know if they was gonna get shot or not.”

Unlike Clarence Brockman, who deployed overseas with the 80th Infantry Division and served his entire tour in the same outfit, twenty-six-year-old Gerald Virgil Myers of St. Joseph, Missouri, went over the loneliest way, as a replacement. Every place he went, he was with strangers. He landed at Omaha Beach in October, four months after D-Day and had the hell scared out of him. “There was a packet of officers and young Army men that were being loaded on the boat that I just got off of that looked like they were, well, we called it ‘battle fatigue’ at that time, because they just never talked. They stared straight ahead, and you could tell that they had been in combat.

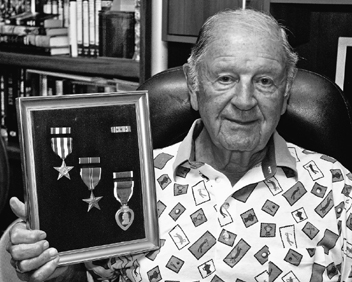

Gerald Virgil Myers has never forgotten the horrors he discovered at Buchenwald. For combat operations with the 80th Infantry Division, he received the Silver Star, Bronze Star, and Purple Heart

.

“We were in this pup tent city, probably a mile back from Omaha Beach, and we were there for two and a half days. They put us in pup tents and told us that we were to watch the bulletin board, because our name would come up on the board to be moved. And if you don’t meet that deadline, you’ll be court-martialed. Well, back in those days, that just scared the hell out of you, so you went down about every two hours to see if your name was on there.

“They had two meals a day, and you lined up and went down to chow, and they gave you a piece of Army bread that weighed about a pound, oh, a half an inch to three quarters of an inch thick. And you held it in your hand and they slapped peanut butter on top of that bread. Then you went down the line, and they put a big piece of warm Spam about a quarter inch thick on top of that peanut butter. And you went to the next place, and they gave you coffee in your canteen cup. And right at the end of the serving line was a captain. He said, ‘Gentlemen, enjoy your T-bone steak.’ He said it a thousand times, morning, noon, and night.”

When Myers’s name finally came up, he and about a dozen other replacements were loaded aboard a truck with a sergeant in charge. The first leg of the journey took them to Neufchâtel. Half a day there, and Myers was loaded onto another truck and, after a five-hour ride, arrived at Pont-à-Mousson. Several of the soldiers were off-loaded, and he recalls the sergeant telling the remaining men, “Now, you’re close to the front, and if you hear artillery come in, you better duck. You’ve never seen what shrapnel can do to you.”

“All of a sudden,” Myers recalls, “my God, the biggest explosion went off you ever heard. Well, if you’d have turned that truck upside down, you couldn’t have evacuated it any faster than we did, and we hit the ditch, and it was muddy water, and we didn’t even think about it. The sergeant came over about that time, and he says, ‘What the hell is the matter with you guys?’ He said, ‘Don’t you know that’s outgoing?’ It was a battery of 155s, just over the hedgerow.”

After another short ride, they got off the truck, went into the woods, and were introduced to First Sergeant Percy Smith, all five feet five of him. He said, “We’re glad to see you, because in the last week, we have lost half of our company.” Myers volunteered for the 60mm mortar section, not knowing that it had lost five men just that week. He spent the rest of the afternoon learning his new job.

The very next day, they got their first taste of battle, capturing a forced-labor camp where the Nazis had imprisoned two hundred Polish workers behind a ten-foot-high barbed-wire fence. In the process, one of the new men who’d been on the truck with Myers all the way up from the beach was killed by a chunk of shrapnel in the head. He’d never even fired his rifle.

Myers fought with the 317th Infantry Regiment of the 80th Division through the Battle of the Bulge in January 1945, suffering frostbite twice because the men had only summer uniforms. He recalls getting winter boots in the latter part of February. His outfit went in on the south side of the Bulge, near Ettelbruck, and from there went to Heiderscheid, Luxembourg, where the fighting was vicious, without a lull, twenty-four hours a day. The snow was fifteen inches deep, and the temperature often hit fifteen degrees below zero. The American forces suffered 83,000 casualties; 18,000 were killed, the rest were injured or captured. Now a buck sergeant, Myers suffered a shrapnel wound in one arm, but since he could still walk and carry a rifle with his other arm, he stayed on the line.

On February 12, the men of Myers’s unit got an emotional boost: they entered Germany, crossing the Saar River near the town of Dillingen. He recalls thinking, “Now we’ve got them on the run,” but that was before they encountered what he calls “those damned hills. More like up in Georgia, north, northeast of Atlanta. They’re not really mountains like the Rocky Mountains; they’re more like the Ozarks in Missouri.” There was still no discussion of concentration camps.

On March 26, while under fire from 20mm antiaircraft guns mounted in quads, they crossed the quarter-mile-wide Rhine River at Mainz in plywood boats with paddles and a small outboard motor that the combat engineer used to bring the boat back to the western bank to pick up more troops. After an interlude where he single-handedly captured fifty-six German soldiers along with the enemy’s map of artillery installations in the area, earning a Silver Star for what still, to him, seems to be an amusing episode, they made their way through Wiesbaden to Kassel, down through Erfurt, and into Weimar, where they were assigned to police the city and maintain order. It didn’t take long before they spotted “fellows in striped suits walking around, skinny as hell.”

His company commander was able to communicate in Polish with the men, and he called Myers’s first sergeant over and said, “This guy says there’s a camp outside of town here. Go out and see what it is.” That’s how First Sergeant Percy Smith, Myers, and Don Smith came to be driving a jeep toward Buchenwald. “As we rounded the hill and came up behind these trees, here was a camp that had, we estimated, over thirty barracks up there. And the people were standing, holding on to the fence, and they could see you, but they were looking right straight through you. They just were so malnutritioned that they could hardly stand up, and they were nothing but skin and bones.

“And there was a couple of guys that was taking a bath from a wash pan, just using a cloth. And they had their shirt on, but the rest of it was bare, and you couldn’t believe that people that were so skinny could still stand up, but they did.”