The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (42 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

The former prisoners of those Germans stood by the side of the road, waving at the GIs, saying thank you in a variety of languages. Then the troops moved on without stopping to question the people on the road. “The war was on—we didn’t stop, we kept moving. But the guys were so furious that the next couple villages mostly burned down. They were just so mad, they just hated the Germans at that point. And I think later, those poor people that lived there, they didn’t know what that was about. They didn’t know why the Americans were so furious or what had happened. All they knew is they caught hell. And same way with those poor guys that were driving those prisoners. They were probably forced to do that,” he says, with a charity rarely exhibited by ex-GIs who had seen the camps.

Twenty-year-old American kids who’ve killed the enemy and seen their buddies die aren’t big on introspection. They’re just trying to process what they’ve seen. Caughey said it broke down into two simple phrases: “You just can’t believe it. How could people do that? And that,” he says, “was just a taste of what was to come.”

John Fague, now a retired veterinarian in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, was also in B Company of the 21st Armored Infantry, also twenty years old at the time they found the column of prisoners on the road. “They had all these inmates on the road, they were in their pajama pants is what I called them, striped pants. And it just seems like there was hundreds of them on the road. Some of them would get down on their knees and thank us, but, of course, we couldn’t do anything for them because we weren’t equipped for that. And I always remember my dear captain, he was chasing one of the guards down through the field and swinging his carbine—why he didn’t shoot him, I don’t know.”

When some concentration camp inmates saw the German-born American soldier Werner Ellmann, they were literally frightened to death: he spoke German, wore a uniform, and had a gun

.

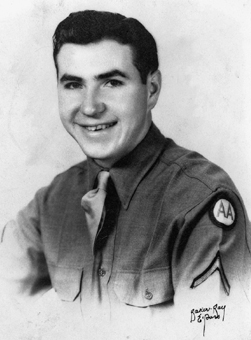

Werner Ellmann was born in Germany in 1924, but at the age of five, along with his mother and younger brother, he emigrated to the Chicago area, where he still lives. Ellmann was drafted and had to convince the Army that he could do more good for them in Europe, because of his language skills, than he could in the Pacific.

He fought at Bastogne with the 101st Airborne Division when it was surrounded, the Nazis demanded surrender, and the division’s acting commanding general, Anthony McAuliffe, famously responded with one word: “Nuts!”

Ellmann suffered frostbite in that horrendous winter but was never wounded. His closest call came one night. They’d been warned about Germans using English-speaking troops disguised in U.S. uniforms to misdirect traffic or get in close enough to kill. It was a psychological tactic that played hell with the American troops. Soldiers in the line were constantly being challenged with questions like “How many touchdowns did Babe Ruth score?” That sort of thing didn’t make Ellmann very comfortable. “You know, all these kinds of questions—my thought was always that, Christ, they would know that as well as I do because they grew up there. And then they went back.” If you’ve seen the movie

Stalag 17

, you understand.

Ellmann remembers his encounter with the fake Americans quite well. “One night, the captain and I had to go through the lines to get to the British, and we’d usually leave around one or two in the morning, and the windshield for the jeep is down. And on the road are these two American soldiers. And I didn’t stop, but that captain said, ‘Stop, let’s see what’s going on.’ Okay, well, right off the bat I thought something was wrong, because these guys had pretty new uniforms. And you didn’t have that at the Bulge. And they’re already in the jeep, and they’re sitting in the back and the captain and I are sitting in the front. And I kind of took his hand and squeezed it, giving him a signal. I slammed on the brakes, and these guys tumbled right over our heads. And it turned out that they were Germans. I mean, it was horrible.”

Ellmann had his own encounter with concentration camp inmates on the road. He was part of a long convoy moving quickly toward a rendezvous with the Russians when suddenly “We don’t know what the hell’s going on. The first thing I saw, skeletons walking in certain kinds of uniforms. I go up to three or four of them, and I say, ‘What goes on?,’ and it’s in German.

‘Was ist los hier?’

And they died in front of me, in fright.

“Yeah, God, they were so close to dead anyway. All of a sudden, the guy collapses. In the meantime, my driver’s feeding somebody, and he dies on him. He just falls down, and he’s gone. We’re in such amazement and such confusion; we don’t know how to make anything out of this.

“It’s so hard to describe because the condition of these people—they are obviously civilians and not soldiers. They don’t have guns; we do. And they look at us, and they think we’re Germans. I speak German, I’m in uniform, and I got a gun. And they’re just scared shitless.”

The obvious question: there were no American flags around? “No, that’s movies,” says Ellmann. “We’re just a bunch of hard-fighting guys on our way to a river to hook up with the Russians. We’re pretty sure the war’s almost over.”

Albert Adams was in the Headquarters Company of the 21st Armored Infantry Battalion, and he had a similar experience while on the road that eventually led to Mauthausen. The twenty-two-year-old who’d honed his shooting skills as a kid hunting deer in Washington State still remembers seeing prisoners coming out of the camps, “and we gave them all the food we could possibly give them, and we killed them. ‘Death warmed over,’ we called them.”

Adams’s half-track was slowly moving down the road when he came upon a scene that’s stuck in his mind for more than sixty years. Prisoners had knocked a man off a bicycle, and they were beating him to death with the bike. He learned that the man had been one of the guards in the camp.

When they got to the camp itself, which he believes was Mauthausen, Adams was confronted by a completely unexpected sight: women behind a gate asking to be let out. “I found out later they were comfort ladies for the German soldiers. And they were young and well fed and well dressed. They had the barracks right inside the first gate.”

While he was standing there trying to figure out exactly what he was looking at, a male prisoner came up to him. “He spoke very good English. I still don’t know who he was or what he was, and he said, ‘Can I borrow your carbine for a little while?’ And I said, ‘Well, what the hell, why not?’ I figure he had a good use for it. So [he goes away and] I could hear some shots, and he came back and gave me the gun back. He said, ‘Well, now there’s several of them that you won’t have to take to court.’ And I said, ‘Several what?’ And he said, ‘Kapos.’ And I said, ‘What’s a kapo?’ He told me they were prisoners in charge of barracks, like the one that got killed [with the bicycle].”

That business out of the way, the prisoner took Adams on a tour of the camp. The first thing he saw was buses used to transport prisoners from Gusen to Mauthausen, killing them in the process. “All of these buses had an enclosed thing for the driver, airtight, and the exhaust gases went back into the bus, and they killed the majority of the people getting from Gusen to Mauthausen.” Each bus held forty or fifty people.

“And then the next thing he showed me was the gas shower. It was a shower room that held several hundred people, and the showerheads didn’t put out water, they put out gas. So they would eliminate that group of people that way.”

Adams says there were thousands of bodies strewn about the camp, which, of course, stank. “The ovens where they cremated them were still smoking hot when I went in. They’d probably used them the day before. There were bones in them, not bodies.”

His guided tour continued with a stop at the rock quarry, where he was told how the Germans would kill prisoners by forcing them to carry huge rocks up the 180 steps from the bottom to the top all day long. If the work didn’t kill them, the SS guards would shove them off the cliff and watch them fall to their death on the rocks below. The prisoner, whose name and nationality he never learned, took him to a building where medical experiments had been conducted and corpses dissected. Adams says that the psychological impact of what he was seeing was blunted because he and his buddies had seen terrible things during the war, including the Americans’ brutal response to the Malmédy massacre, which had included an “absolutely no prisoners, none” unofficial order. Nevertheless, while Adams has told the woman he married in 1946 about some incidents during the war, including what he did to get a Silver Star, Bronze Star, and Purple Heart, he’s never told her or their five children and thirteen grandchildren about the concentration camps.

As the first troops from the 11th Armored were entering Mauthausen, Stanley Friedenberg of the 65th Counter Intelligence Corps Detachment was coming into Linz. Since leaving the Ohrdruf concentration camp, he and his small team had been following the Danube all the way into Austria, not knowing if they were entering the country as liberators or conquerors. “So,” he says, “the people threw flowers at us, and we kept submachine guns on our laps.” The first thing they heard in Linz was that the 11th Armored had discovered a huge concentration camp across the river and just twelve miles to the southeast.

Hurrying to the camp, he saw a sight he’s never forgotten. “The thing I remember is the inmates, wearing the striped pajamas, none of them weighing more than a hundred pounds. Haggard, unshaven, disease-ridden, clinging to the barbed wire with their hands, saying nothing. But the fact that they said nothing said a lot.”

As he describes the scene while seated on the patio of his winter home in Placida, Florida, the retired lawyer doesn’t even realize that his hands have formed themselves into claws, as though he, himself, were hanging from the Mauthausen barbed-wire fence. When I point this out, he says, “When we visited Yad Vashem [the Holocaust Memorial] in Israel, they had a series of photo murals there, and the last photo mural was maybe four by eight feet, the exact same thing, of the men of Mauthausen clinging to the wires. I came around a corner and came face-to-face with it, and I’m not an emotional man, but I sat down and just cried.”

At the Mauthausen gate on May 5, because he arrived in an unmarked jeep wearing a uniform that concealed his rank and had the authority that counterintelligence agents carry, he was able to order the GIs who wanted to open the gate to keep it closed. He recalls telling them it would be bad for the prisoners. “They’d wander over the countryside, the Germans will harass them, they’ll die of starvation and disease. Just keep them here and get on your radio and call back for medics, food, and so forth.” Then he entered the camp.

“They had these long barracks with five-tier-high beds, little narrow aisles between them, and the Sonderkommandos, who were the Jewish people used as help by the Nazis and given a little extra food, used to go through there every morning and clean out the dead bodies. And the place smelled; there were still many, many people laying in the bed too sick to get out, just moaning.

“It was so emotionally involving, I just want to go in and see what I can do. I couldn’t do a damned thing except hope for some professional help to come there. And we walked through it, and I can’t say how long it was before medics and food wagons came, but it was possibly the end of that day, and they started setting up medical tents there. We set up a separate detachment for Mauthausen. We had three or four men there just to cover it, and try to get who were the guards, the atrocities we could document. Our mission had somewhat changed by now. Now we’re involved in war crimes and tracking down war criminals as well as counterintelligence.”

George Sherman was a member of the 41st Cavalry Squadron of the 11th Armored Division. The nineteen-year-old from Brooklyn had enlisted in the Army Air Corps just two months before his high school graduation, but he had turned out to be color-blind and thus unqualified for flight training. It wasn’t a problem in an armored outfit, however. It was the Thunderbolts who were sent to the town of Malmédy, where elements of the German 1st SS Panzer Division had massacred at least seventy-one American POWs. Their job was to winch the frozen American bodies out of the field where they’d been murdered and up to a road where they could be put in body bags and loaded onto trucks.

The day Sherman arrived at Mauthausen started with a simple assignment: look for the Russians coming toward them from eastern Austria. They were patrolling on roads a few miles east of Linz in M24 light tanks when they began smelling an awful odor. Moments later, they came to a big wooden entryway and heard a lot of yelling on the other side. One of the tanks drove through the gate, and then the entire platoon of tanks rolled inside. Sherman says, “We were greeted with the sights, the piles of bodies, these people walking around like God knows what. We dismounted, and the scout sergeant radioed back to the squadron headquarters. He couldn’t explain what the heck it was. And about half an hour or forty-five minutes later, a full tank battalion came up from the 41st, rumbling down with about twenty-odd big Sherman tanks.”