The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (29 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

The GIs removed the remaining survivors, putting those who were too weak to walk, like Cohen, in a wagon. They were taken to a nearby farm, and it was made clear to the farmer that nothing bad had better happen to the survivors. Cohen says the farmer, who’d been doing the “We didn’t know,

nicht Nazi”

routine, was very scared. “They thought that the Americans are going to do to them what they did to us.

“When I came to the farm, they wanted to give me [something] to eat. I said, ‘No, I don’t want to eat. I need a hot bath.’ And I took off my clothes, and the clothes were full of lice. They would walk away themselves. And then I took the tub in the stable. My skin was burning from the bites of the lice, but I relaxed so much. And then they came and fed me.”

Israel Cohen was bounced among several different hospitals until his medical conditions were controlled and he began putting on weight. He tried to reconnect with family members, only to learn that they’d all perished in the Holocaust. He spent three years in a TB sanatorium in Switzerland. In 1951, he moved to Canada, where he lives today with his wife, five children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

He never lost his faith in God. “I talk to people, and they ask me, ‘Why did it happen?,’ and I say, ‘I don’t know, and nobody knows.’ Hashem [God] wanted him to be saved. I know that someone lately had a video and said he was rescued by chance. I got up, and I said that ‘You win the lottery, it could be chance. You win twice the lottery, it could be chance. But if you win the lottery seven, eight times in a row, it can’t be chance.’ I was seven, eight times just before being killed, and I was saved at the last minute, and this can’t be chance.”

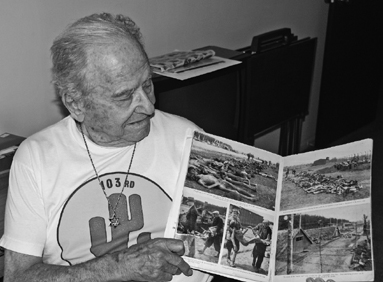

Monroe “Monty” Nachman at home in Skokie, Illinois, with the 103rd Infantry Division yearbook showing pictures at the Landsberg area camps. Note the triangular, semiunderground barracks that were unique to the Kaufering camps

.

Five-foot, five-inch Monroe “Monty” Isadore Nachman was a tough kid from Detroit who, just before Pearl Harbor, joined the National Guard’s 6th Cavalry unit because he had a low draft number and didn’t want to be in the infantry. He was in the twelfth grade when he got tossed out of high school for fighting in class. “A guy called me a sheeny, and I hit him.” His mother wanted him to go back, but he was tired of fighting. “I lived in a half-Jewish, half-gentile neighborhood, and every day I had to go by St. Mary’s Church, and every day I was fighting. My mother called me a

vilde chaya

—a wild animal—but she didn’t understand. It was ‘Here comes the Jews, or here comes the kikes.’ [My friends and I are] the type of guys who don’t take that kind of stuff, so every day, we would fight.”

Anti-Semitism wasn’t a theoretical concept for Monty Nachman. They listened to Father Charles Coughlin’s broadcasts on Detroit radio—“he was a

mamzer

[bastard] from the first go, he was a bad guy”—and they paid attention to the headlines from Germany. He knew about Kristallnacht, about the Jews being killed.

He ultimately found himself enrolled in OCS and doing well, but the Army wanted him in the infantry, and he said no. So he was tossed from officers’ school and sent to Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, to join E Company, 2nd Battalion, 411th Regiment, of the 103rd Infantry Division. It’s where he found out how the Army works. He’d made it all the way up to sergeant, only to get a new commander, an anti-Semitic captain, and he ended up being busted back down to private.

In October 1944, the 103rd went to Marseilles, rode boxcars north, and was committed to action at Saint-Dié, near Strasbourg. They lost fifty-five men, wounded and killed, the first day. Though Monty was aware of Germans’ mistreatment of the Jews, the Army had never told the troops about concentration camps. His introduction was much the same as most other combat soldiers’: the smell. On April 27, his outfit was walking near Landsberg. He was carrying the burp gun he’d traded for; it’s a tanker’s weapon, but an armored guy had wanted a carbine, so they’d swapped. “All of a sudden, when we’re approaching this place here, it started to smell like a different smell, a terrible, terrible smell. And it never goes out of your nostrils. You always remember that smell, you can never forget what you see. And we came into this place, and, my God, it was horrendous. A few of my guys threw up.

“These underground huts, and bodies are lying all over the place, filthy, and the stink around there was unbelievable. I talked to some people there in Yiddish, and they said that whoever could walk, the Nazis were taking to Dachau to kill off. So we left, we got in our jeeps. We caught up with them.”

It took his company about forty-five minutes to come upon the death march. “We saw a line of people, walking if they could walk, stumbling all over the place. The guards were around, and we caught up and killed them. They threw down their arms, and I just plain shot them. There were about a dozen or so. And the other guys shot them, too. We didn’t take any prisoners.” They turned the forty or fifty surviving inmates over to another outfit, “and we went back to our task, because we were way into Germany now.”

His hands-on contact with the Holocaust lasted less than half a day, but, as he said, the memories don’t go away. Flashbacks happen without warning. Nightmares occur. “I used to get crazy, you know. It’d come back. You see the bodies. We were living with my in-laws in [Chicago’s Albany Park area], and they had this party to introduce the new son-in-law. Now, I never lacked for words in my life. I’m talking, and all of a sudden, I’m seeing bodies laying all over there. I felt like a

shtumi

[mute]—you know what I mean? I couldn’t talk.”

Monty Nachman never spoke about what he saw at Landsberg until 2003, when a veteran at one of their reunions urged the men to go on the record. Since then he’s been outspoken, taking on the Holocaust deniers, including the tenured professor at nearby Northwestern University whose book made big headlines in Skokie, Illinois, where Nachman and his wife live. He recognizes the bookends of his life—fighting anti-Semitism as a high school kid and now again as a ninety-year-old. He quotes his mother, who used to say

“Shvertz azayan Yid”—

It’s hard to be a Jew.

APRIL 28, 1945

LANDSBERG, GERMANY

J

ack Kerins was born on March 30, 1912, making him the oldest veteran interviewed for this book. In fact, he was one of the oldest draftees in the 63rd Division on its last day in Landsberg. Kerins was thirty-one when he was drafted; he’d had deferments because he was the sole support of his mother in the tiny town of Farrell, Pennsylvania, about seventy-five miles north of Pittsburgh, but when the Army got desperate for bodies, the deferments were taken away, and in late 1943, he was shipped to Europe with just part of his division—no artillery, no support units. They were thrown into combat without really being ready and took on the 17th SS Panzers while units farther north fought in the Bulge. After a year and a half of combat, he’d earned a Purple Heart at the Siegfried Line for a concussion from an incoming oversized German artillery round that killed his company commander and by all rights should have killed him. He was also awarded a Silver Star and an unwanted battlefield commission from tech sergeant to second lieutenant and platoon leader.

Jack Kerins was thirty-one years old when he was drafted and ultimately served with the 63rd Infantry Division, which liberated the Landsberg camps. At age ninety-six, he is the oldest veteran interviewed for this book

.

April 28 was a beautiful, sunny day, and from the jeeps of the 2nd Platoon of D Company, 255th Infantry Regiment, they had an incredible view of the Bavarian Alps’ snow-covered peaks. Kerins’s unit was assigned to antiaircraft defense for the column—“only a show,” he says, because the .50-caliber machine guns were not likely to be effective against planes like the Luftwaffe jet that had buzzed them the day before. They had gotten to the far side of Landsberg when a messenger stopped them, saying, “Hold up, don’t chase the Germans any farther than right here.” They disembarked from their jeeps, and that’s when he saw them.

“I saw these pajama-clad prisoners coming down the little streets. They were holding each other. A lot of them could hardly walk. And the boys were directing them to go where there’d be somebody to take care of them. Suddenly one of the DPs [displaced persons] bolted from the line and ran over to me, grabbed my hand, kneeled down, and began kissing my hand, saying

‘Danke, danke,’

over and over again. Apparently he picked on me as I was the only officer he saw as he rounded the corner. The physical condition of the man was inconceivable. I took hold of him by the arm and raised him up and could not believe what I saw. He had no flesh on his arm, only skin and bone, his eyes were sunken, he had very little hair and only two teeth visible on his upper jaw. His smile, though, was contagious, and the boys around me started calling him Joe and began to offer all of them rations. All of them dug in their pockets and were giving them chocolate bars and K rations—loading them up. I told them, ‘Be careful, boys, they’ll be sicker now than they were before.’