The Korean War: A History (33 page)

Read The Korean War: A History Online

Authors: Bruce Cumings

An underground factory in North Korea.

U.S. National Archives

The United States intervened first for the defense, and then for the offense: the worst happened, their territory was occupied by an American army. But China determined to defend its borders and support its comrades in arms. Soon the battle devolved into inconclusive

warfare along the central front, negotiations opened, and two years later an armistice was signed—except that the unhindered machinery of incendiary bombing was visited on the North for three years, yielding a wasteland and a surviving mole people who had learned to love the shelter of caves, mountains, tunnels, and redoubts, a subterranean world that became the basis for reconstructing the country and a memento for building a fierce hatred through the ranks of the population. The leaders who survived draw a straight line from 1932, when their struggle began, through this terrible war, down to the present. Their truth is not cold, antiquarian, ineffectual knowledge, but “a regulating and punishing judge,”

10

a burned-in conviction that their overriding goal is to persist until victory is finally won, and if the whole of the state needs to be subordinated to this task, so be it.

Thus we arrive at our absurd predicament, where the party of memory remains concentrated on its main task, perfecting a world-historical garrison state that will do its bidding and hold off the enemy, and the party of forgetting and never-knowing pays sporadic attention only when it must, when the North seizes a spy ship or cuts down a poplar tree or blows off an A-bomb or sends a rocket into the heavens. Then the media waters part, we behold the evil enemy in Pyongyang—drums beat, sabers rattle—but nothing really happens, and the waters close over until the next time. We don’t approve of them but pay little attention and pat ourselves on the back, while they mimic Plato’s

Republic

or monolithic Catholicism or Stalin’s cadres: they engineer the souls of their people from on high, starting at the beginning just as their neo-Confucian forebears did, when a human being is all innocence and wonder, and continuing until they have at least the image if not the reality of perfect agreement and coherence, a “monolithicism” (their term) seeking a one-for-all great integral that will smite the enemy. They think they know good and evil in their bones, but we aren’t so sure.

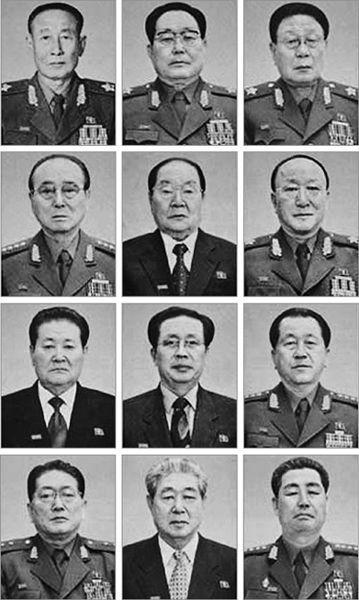

North Korea’s National Defense Commission in 2009.

Notice how the inertia of deterrence (all sides are thoroughly deterred in Korea and have been since 1953) yields an ever-increasing capability for mayhem not just on one side, but on all sides. A new Korean War could break out tomorrow morning, and Americans would still be in their original state of overwhelming might and unfathomable cluelessness; armies ignorant of each other would clash again, and the outcome would again yield its central truth: there is no military solution in Korea (and there never was).

In 2009 the North Korean government was run by a National Defense Commission whose twelve members could constitute a short list of honored Korean War veterans. They are the keepers of the past, and the prisoners of it. This party of memory has braced itself against the pressures of past, present, and future since 1945, up against the greatest military power in world history. Americans think they know this story, of a vain, feckless, profligate, cruel, and dangerous leadership, symbolized by Kim Jong Il, but they are very wide of the mark. As for the leaders of that “indispensable power,” they know not the nature of this war nor the qualities of their enemy. This is not a matter of forgetting; it is a never-knowing, a species of unwilled ignorance and willed incuriosity, which causes them time and again to underestimate the adversary—and thereby confer priceless advantage upon him. Finally, there is the evil, grinning image of the war itself, reaper of millions of lives and all for naught, because it continues, it is the odds-on survivor, it never ends. It returns in myriad forms—memory, trauma, ghosts, repression, the quotidian coiled tensions along the DMZ—to taunt the living, as the only “perfect tense” to survive Korea’s tragedies since the national division.

The Pacific War began in 1931 and ended in 1945, just as the Korean War began in 1945 and has never ended, even if the fighting stopped in 1953. Nor has the North Korean–Japanese war that began in 1931–32 ever ended; South Korea normalized its relations with Japan in 1965, but through many failed negotiations Pyongyang and Tokyo have never normalized or reconciled—and thus

there has been no “closure” to either war from the North Korean standpoint; neither has come to an appropriate resolution. These are not the American demarcations for these wars, of course, but many histories in Japan and Korea conventionally begin these two conflicts in 1931 and 1945, and the history-obsessed North Koreans trace a straight line from the present back to that long-lost first day of March in 1932. Those who suffer terrible wars have a finer sense of when they begin and when they end.

If Americans have trouble reflecting on this “forgotten war” as a conflict primarily fought among Koreans, for Korean goals, they should hearken to the great chroniclers of their own civil war. International involvement was important—and particularly U.S. involvement—but the essential dynamic was internal to the

peninsula, to this ancient nation that has known a continuous existence within well-recognized boundaries since the time of Mohammed. Korea remains divided so long after the Berlin Wall fell because this war cut so deeply into the body politic and the Korean soul.

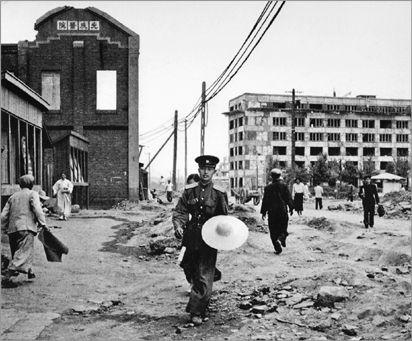

Strolling through a rebuilding Pyongyang in 1957.

Courtesy of the artist, Chris Marker, and Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Eventually the Korean War will be understood as one of the most destructive and one of the most important wars of the twentieth century. Perhaps as many as 3 million Koreans died, at least half of them civilians (Japan lost 2.3 million people in the Pacific War). This war raging off Japan’s coast gave its recovery and industrialization a dynamic boost, which some have likened to “Japan’s Marshall Plan.” In the aftermath of war two Korean states competed toe-to-toe in economic development, turning both of them into modern industrial nations. Finally, it was this war and not World War II which established a far-flung American base structure abroad and a national security state at home, as defense spending nearly quadrupled in the last six months of 1950, and turned the United States into the policeman of the world.

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTSI would like to thank Jonathan Jao of Random House for suggesting the idea of this book to me, for his sharp and careful editing, and for shepherding the manuscript through the various stages of preparation and publication. John McGhee provided deft and meticulous copy editing, for which I am most grateful. Jessica Waters and Dennis Ambrose of Random House were also courteous, highly skilled, and most helpful. Two of my Ph.D. students at the University of Chicago, Su-kyoung Hwang and Grace Chae, taught me much through their work on the Korean War. Many, many others have aided my scholarship since I published my first book on this war in 1981, but I want to particularly thank Marilyn Young, the late James B. Palais, and Wada Haruki. Finally, my gratitude to Meredith, Ben, Ian, and Jackie for their love and support.

OTES

A

RCHIVE

G

LOSSARY

| FO | British Foreign Office |

| FR | Foreign Relations of the United States |

| HST | Harry S Truman Presidential Library |

| MA | Douglas MacArthur Archives (Norfolk) |

| NA | National Archives |

| NDSM | Nodong Sinmun (Worker’s Daily), Pyongyang |

| NRC | National Records Center |

| PRO | Public Record Office (London) |

| RG | Record Group |

| USFIK | U.S. Forces in Korea |

NTRODUCTION

C1.

Hastings (1987), 105.

HAPTER

1: T

HE

C

OURSE OF THE

W

AR

1.

Tim Weiner, “Robert S. McNamara, Architect of a Futile War, Is Dead at 93,”

New York Times

(July 7, 2009), A1, A9–10.

2.

Michael Shin’s forthcoming book is the best analysis of this phenomenon.

3.

Several veterans have told me that they thought fragging was more common in Korea than in Vietnam. I have no way of judging this matter.

4.

William Mathews Papers, box 90, “Korea with the John Foster Dulles Mission,” June 14–29, 1950.

5.

Acheson Seminars, Princeton University, Feb. 13–14, 1954. (These seminars were designed to help Acheson write his memoirs.)

6.

For documentation see Cumings (1990), ch. 14.

7.

I discuss this episode at greater length in

War and Television: Korea, Vietnam and the Persian Gulf War

(New York: Verso, 1992).

8.

Noble (1975), 20, 32, 105, 118–19.

9.

Acheson Seminars, transcript of Feb. 13–14, 1954. Kennan quoted from remarks he wrote down in a notebook in late June 1950. Gen. Omar Bradley also noted Acheson’s domination of the decision process, in Bradley (1983), 536. Kennan supported Acheson’s decisions in a memo written on June 26, saying that “we should react vigorously in S. Korea” and “repulse” the attack. If the United States failed to defend the ROK, he thought, Iran and Berlin would then come under threat. (Princeton University, George Kennan Papers, box 24, Kennan to Acheson, June 26, 1950.) For Acheson’s discussion of the decisions, see Acheson (1969), 405–7.

10.

Truman Presidential Library (HST), Presidential Secretary’s File (PSF), CIA file, box 250, CIA daily report, July 8, 1950.

11.

Thames Television interview, Athens, Georgia, September 1986. See also Thomas J. Schoenbaum,

Waging Peace and War

(New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 211.

12.

Korean War veterans quoted in Tomedi (1993), 186–87, 197–205; Sawyer (1962), 124–26, 130, 134, 141, 153.

13.

Princeton University, Dulles Papers, John Allison oral history, April 20, 1969; ibid., William Sebald oral history, July 1965. Sebald quotes from his diary “words to that effect” from MacArthur; see also Casey (2008), 28, 68.

14.

New York Times

, July 14, 1950.

15.

New York Times

, July 19, 1950.

16.

New York Times

, Aug. 21, 1950. See Christopher Simpson’s searing account of the bloody Nazi suppression of guerrillas in the Ukraine, which he considered “without equal in history.” Christopher Simpson,

Blowback: America’s Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War

(New York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1988), 13–26.