The Korean War: A History (27 page)

Read The Korean War: A History Online

Authors: Bruce Cumings

In the crisis of the Inchon landing several major massacres of political prisoners occurred. During the Northern occupation Seoul’s West Gate prison held seven thousand to nine thousand people, most of them imprisoned in the last month of the occupation; they consisted mostly of ROK police, army, and rightist youths. On September 17–21, 1950, all these prisoners were moved to the North by rail, except for those who could not walk, who were shot. American sources counted 200 in graves, and estimated the total killed at 1,000; Reginald Thompson saw “the corpses of hundreds slaughtered in the last days by the Communists in a frenzy of hate and lust.” In Mokpo 500 were slaughtered, another 500 were killed in Wonsan when the North Koreans withdrew, and various mass graves, presumably containing those executed by the North Koreans, were found by advancing troops. When Pyongyang was occupied, American sources reported finding thousands of corpses in a wide trench near the main prison, and 700 people were said to have been executed as the North Koreans left Hamhung.

38

But other allied forces in the North reported little evidence of atrocities by the

retreating Communists. A November 30 UN Command document stated that “no reports of any [enemy] atrocities have been received from the areas recently taken by UN troops.”

39

A detailed UNCURK file documents with photographs and interviews of survivors the massacre of political prisoners in Chonju and Taejon, carried out by KWP cadres and local political agents. Most of the victims were made to dig a large pit, then shot and tossed into it; the majority were ROK policemen and youth group members. Another incident of a mass killing was properly and fully investigated, but with equivocal results. A KMAG adviser reported that in the last week of September 700 civilians had been “burned alive, shot or bayoneted by [the] Commies before leaving Yang-pyong,” in Kangwon province not far from the 38th parallel; pictures of the victims were taken, and witnesses said most of the dead were members of the police and rightist youth groups. But when an UNCURK team investigated this massacre they found about forty civilian bodies, and a nearly equal number of executed North Korean soldiers, still in uniform. An investigation by Vice-Consul Philip Rowe turned up only nine bodies. Local people said the rest had been carried off by the victims’ families. Rowe was willing to believe this, but he was nonetheless unable to verify the KMAG account. He did not mention the murdered KPA soldiers.

40

The evidence of North Korean atrocities in the South is nonetheless damning. For what it is worth, captured documents continued to show that high-level officials warned against executing people. Handwritten minutes of a KWP meeting on December 7, 1950, apparently at a high level, said, “do not execute the reactionaries for [their] wanton vengeance. Let legal authorities carry out the purge plan.”

41

It wouldn’t be much solace for the victims and their families.

Based on American and South Korean inquiries, the total massacred by North Koreans or their allies in the South was placed at 20,000 to 30,000.

42

I do not know how the figure was arrived at. UNCURK reports suggest a significantly lower figure; furthermore,

the UNCURK investigations were balanced, whereas the Americans and South Koreans never acknowledged ROK atrocities. Americans who took part in planning for postvictory war crimes trials claimed that the North Koreans and the Chinese had killed a total of 29,915 civilians and POWs; it is likely that this figure includes some of the atrocities committed in southern Korea in the summer of 1950, of which the authorship is in dispute.

43

We are left with the conundrum that the DPRK, widely thought to be the worst of Communist states, conducted itself better than did the American ally in Seoul. To kill 30,000 and not 100,000, though, offers no comfort.

EASURES

T

AKEN

: T

HE

O

CCUPATION OF THE

N

ORTH

United Nations forces occupied the North under a governing American policy document (NSC 81/1) that instructed MacArthur to forbid reprisals against the officials and the population of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) “except in accordance with international law.” On September 30, the day before ROKA units crossed over to the North, Acheson said the 38th parallel no longer counted: “Korea will be used as a stage to prove what Western Democracy can do to help the underprivileged countries of the world.”

44

The ROK saw itself then, as it does today, as the only legitimate and legal government in Korea, and in 1950 sought to incorporate northern Korea under its aegis on the basis of the 1948 constitution. The United Nations, however, had made no commitment to extending the ROK mandate into the North (either in 1948 or in 1950), and the British and French were positively opposed to the idea—even suggesting that ROK weakness and corruption, and the possibility that it might “provoke a widespread terror,” raised questions about whether it should be allowed to reoccupy

the South.

45

The State Department’s plans for the occupation of the North called for the “supreme authority” to be the United Nations, not the Republic of Korea; failing that, it would set up a trusteeship or an American military government. The department categorically rejected the ROK claim to a mandate over the North and instead called for new UN-supervised elections. (The South wanted elections for only a hundred northern seats in the ROK National Assembly.) There may also have been secret American plans to remove Rhee: M. Preston Goodfellow cabled him on October 3, saying, “Some very strong influences are at work trying to find a way to put some one in the presidency other than your good self.”

46

On October 12 the UN resolved to restrict ROK authority to the South for an interim period. In the meantime, the existing North Korean provincial administration would be utilized, with no reprisals against individuals merely for having served in middle or low-level positions in the DPRK government, political parties, or the military. DPRK land reform and other social reforms would be honored; an extensive “re-education and re-orientation program” would show Koreans in the North the virtues of a democratic way of life.

47

In the event, however, the ostensible government in the North had nothing to do with United Nations trusteeships or State Department civil affairs plans: it was the Southern system imposed on the other half of the country. The extant “national security law” of the ROK, defining North Korea as an “anti-state entity” and punishing any hint of sympathy or support for it among its own citizens, provided the legal framework for administering justice to citizens of North Korea—under international auspices but by no means under anything that would resemble the rule of (any) law. North Korea was the only Communist country to have its territory occupied by anti-Communist armies since World War II. There this particular episode is alive and well, burned into the brain of several generations, and still governs North Korean interpretations of the South’s intentions even today.

At the time, Rhee made his intentions known to an American reporter on his way back to Seoul:

I can handle the Communists. The Reds can bury their guns and burn their uniforms, but we know how to find them. With bulldozers we will dig huge excavations and trenches, and fill them with Communists. Then cover them over. And they will really be underground.

48

State Department officials sought some mechanism for supervision of the political aspects of the occupation, “to insure that a ‘bloodbath’ would not result. In other words … the Korean forces should be kept under control.”

49

In fact the occupation forces in the North were under no one’s control. The effective politics of the occupation consisted of the National Police and the rightist youth corps that shadowed it; ROK occupation forces were mostly on their own and unsupervised for much of October and November.

50

Washington’s idea that there should be only a minimum of ROK personnel in the North was “already outmoded by events,” Everett Drumwright told his State Department superiors in mid-October. Some two thousand police were already across the parallel, but he thought some local responsibility might result if police who originally came from the North could be utilized. (Thousands of police who had served the Japanese in northern Korea had fled south at the liberation, and Rhee had always seen them as the vanguard of his plans for a “northern expedition.”) By October 20 An Ho-sang (Rhee’s first minister of education) had his youth corps conducting “political indoctrination” across the border.

51

Paek Son-yop, commander of the ROKA 1st Division when the war started, force-marched his troops in a race to occupy his home city of Pyongyang before anyone else, and got there first “by a bare margin of minutes,” Thompson wrote, “his round brown face glowing with pleasure and triumph.”

52

The British government quickly obtained evidence that the

ROK as a matter of official policy sought to “hunt out and destroy communists and collaborators”; the facts confirmed “what is now becoming pretty notorious, namely that the restored civil administration in Korea bids fair to become an international scandal of a major kind.” The Foreign Office urged that immediate representations be made in Washington, because this was “a war for men’s minds” in which the political counted almost as much as the military. Ambassador Oliver Franks accordingly brought up the matter with Dean Rusk on October 30, getting this response: “Rusk agrees that there have regrettably been many cases of atrocities” by the ROK authorities, and promised to have American military officers seek to control the situation.

53

The social base of the Northern regime was broad, enrolling the majority poor peasantry, so potentially almost any Northerner could be a target of reprisals. Furthermore, the South’s definition of “collaboration” was incontinent, spilling over from enemy soldiers to civilians, even to old women caught washing the clothes of People’s Army soldiers—like one found among knots of “emaciated, dirty, miserably clothed” people tied in ropes and being herded through the streets.

54

Internal American documents show full awareness of ROK atrocities: KMAG officers said the entire North might be put off limits to ROK authorities if they continued the violence, and in one documented instance, in the town of Sunchon, the Americans replaced marauding South Korean forces with American 1st Cavalry elements.

55

Once the Chinese came into the war and the retreat from the North began, newspapers all over the world reported eyewitness accounts of ROK executions of people under detention. United Press International estimated that eight hundred people were executed from December 11 to 16 and buried in mass graves; these included “many women, some children,” executed because they were family members of Reds. American and British soldiers witnessed “truckloads [of] old men[,] women[,] youths[,] several children lined before graves and shot down.” On December 20 a British soldier saw about forty “emaciated and very subdued Koreans” being shot by ROK military police, their hands tied behind their backs and rifle butts cracked on their heads if they protested. The incident was a blow to his morale, he said, because three fusiliers had just returned from North Korean captivity and had reported good treatment. British soldiers witnessed men, women, and children “dragged from the prisons of Seoul, marched to the fields … and shot carelessly and callously in droves and shoveled into trenches.”

56

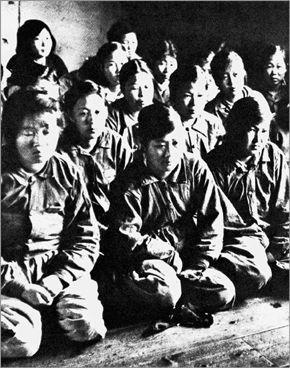

Women guerrillas captured in North Korea, fall 1950.

U.S. National Archives

President Rhee defended the killings, saying “we have to take measures,” and arguing that “all [death] sentences [were] passed after due process of law.” Ambassador Muccio backed him up. He

was well aware of ROK intentions by October 20 at the latest, cabling that ROK officials would give death sentences to anyone who “rejoined enemy organizations or otherwise cooperated with the enemy,” the “legal basis” being the ROK National Security Law and an unspecified “special decree” promulgated

in Japan

in 1950 for emergency situations. This decree may indicate SCAP involvement in the executions; in any case Americans were clearly implicated in political murders in the North.

Secret American instructions to political affairs officers and counterintelligence personnel attached to the X Corps ordered them to “liquidate the North Korean Worker’s Party and North Korean intelligence agencies,” and to forbid any political organizations that might constitute “a security threat to X Corps.” “The destruction of the North Korean Worker’s Party and the government” was to be accomplished by the arrest and internment of the following categories of people: all police, all security service personnel, all officials of government, and all current and former members of the Workers’ Party in both North and South. The compilation of “black lists” would follow, the purpose of which was unstated. These orders are repeated in other X Corps documents, with the added authorization that agents were to suspend all types of civilian communications, impound all radio transmitters, and even destroy “[carrier] pigeon lofts and their contents.”

57

The Korean Workers’ Party was a mass party that included as much as 14 percent of the entire population on its rolls; such instructions implied the arrest and internment of upward of one third of North Korean adults. Perhaps for this reason the Americans found that virtually all DPRK officials, down to local government, had fled before the onrushing troops.

58