The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (60 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Crowds gathered in the square from the previous evening to watch this spectacle. Those who could find no place lined the streets from Notre Dame, where Damiens had made his last confession. The torture lasted for several hours: the horses strained for an hour and a half before they could detach a limb. This obscene performance seems finally to have mobilised philosophers and penal reformers against such festivals of retribution. The search began for a more rational and clinical means of executing justice: still in public, but without the baroque ceremonies and careful gradations of crime and rank that had previously attended executions.

The result, after thirty-five years of debate, was the adoption, in 1792, of a new decapitation machine: a killing device for the age of reason. This, to be applied equally to all condemned without distinction of status, would sweep away all of the macabre ritual that had previously attended the executioner's craft, and consign justice to a simple, easily replicated device, soon dubbed the guillotine after the distinguished doctor who had first designed a prototype. The first execution drew a large crowd but proved rather a disappointment. There was little to see and events proceeded so quickly that the crowd began chanting, ‘bring me back my wooden gallows, bring me back my gallows’.

45

What the disappointed viewers did not realise was that they had witnessed the debut of one of the principal actors in the concluding news event of this era, the French Revolution; an event that would both create the first generation of celebrity journalist/politicians and move the reporting of news, and the development of a news market, into quite uncharted waters.

CHAPTER 16

Cry Freedom

T

HE

mid-eighteenth century had been a period of consolidation for the European press. The development of the weekly journal and monthly magazines extended the range of comment and reflection on political topics. The number of newspapers expanded gradually, as new titles were established and existing papers failed; markets were sustained by a steadily rising tide of new readers. Publishers could earn a good living from providing subscribers with a weekly or thrice-weekly diet of news. But this was not a period of enormous innovation in the news market. In Britain, Parliamentary politics (now settled into an established pattern of annual sessions) ensured that intermittent crises of faction or policy could bring sudden spasms of press fury. A newspaper campaign undoubtedly helped force a humiliating retreat for the ministry in the excise crisis of 1737, and generated a passionate intensity in the opposition to Walpole; but after his fall in 1742 the fizz went out of the bottle. In France the

Gazette

sailed serenely on, protected from competition. The most rapid growth in press activity was away from the major centres of population: in English and French provincial towns (in the latter, it must be said, largely apolitical advertising journals) and in the American colonies.

1

More and more middle-sized communities were served by a single newspaper, usually faithfully modelled on the papers of the metropolitan hubs. By adopting the style of the cosmopolitan centre, on which they largely relied for copy, these papers succeeded by a conscious lack of innovation. An authentic local voice had yet to be developed.

In the last decades of the eighteenth century, and with remarkable rapidity, this busy, prosperous but rather undemanding news world was completely reshaped. In France, England and the American colonies new political controversies brought both a changed role for the press and a vast increase in the number and circulation of newspapers. For the first time, newspapers played

a vital role not only in recording but in shaping political events. It was a critical milestone on the road to a recognisably modern newspaper industry.

Wilkes and Liberty

For the Enlightenment philosopher, John Wilkes made a rather unlikely champion.

2

Unscrupulous, devious and nakedly ambitious, Wilkes combined a rackety private life with a cavalier attitude to public affairs. Continuously in debt and careless of friends and obligations, in the middle years of a hitherto undistinguished career Wilkes discovered both a cause and a flair for publicity. That cause would be the freedom of the press. By the time he had concluded his long struggle the acceptable boundaries of public debate, and the part of the newspapers in the political process, had been radically redrawn.

Wilkes was lucky to be feeling his way towards a public career at a moment when the accession of a new king, George III, had brought a revival of party politics. The change of monarch caused an inevitable turbulence in the governing elite, as the king sought to impose his own stamp on affairs; determined to play an active part in government, George III chose to be advised by Lord Bute, a brittle and sensitive Scot not afraid to use the patronage powers of government to reward his friends and punish his enemies. The discontents of the dispossessed Whigs found a political cause in the negotiations for the unpopular peace that would in 1763 end the Seven Years War. Wilkes was happy to be their most pungent instrument.

Wilkes's famous political paper,

The North Briton

, was a direct response to Bute's attempt to cultivate opinion through his own recently established organ,

The Briton

.

3

Wilkes opened the first issue with a high-minded defence of the principle of a free press, ‘the firmest bulwark of the liberties of this country … the terror of bad ministers’. But if this seemed to promise elevated political philosophy, Wilkes's journalistic principles were better encapsulated by a typically frank avowal to his financial backer, Lord Temple: ‘no political paper would be relished by the public unless well-seasoned with personal satire’.

4

The North Briton

was relentlessly rude, personal and daringly outspoken. Fed a constant stream of damaging information by his Whig allies, a well-sourced exposé of embezzlement in the army concluded with a frantic denunciation of the Secretary of State: ‘the most treacherous, base, selfish, mean, abject, low-lived and dirty fellow that ever wriggled himself into a secretaryship’.

Wilkes did not take this too seriously. Challenged by James Boswell for his abuse of Samuel Johnson when they met on neutral ground in Italy, Wilkes was happy to admit that he held a high opinion of Johnson in private: but

‘I make it a rule to abuse him who is against me or any of my friends.’

5

Here was journalism concerned not with the transmission of news, but as a vehicle of partisan invective.

The North Briton

existed ‘to plant daggers in certain breasts’. Not all his victims would show the same insouciance, but Wilkes did not lack personal courage, and a well-publicised duel with one outraged aristocratic victim, Earl Talbot, only served to enhance his fame. When the ministry attempted to silence him with the promise of office, Wilkes ensured that this too became known.

Much of this would have been familiar from the ferocious press campaign against Walpole. Where Wilkes truly broke new ground was in associating these criticisms with the king personally. In the infamous number 45 of

The North Briton

, Wilkes denounced the king's speech, delivered on behalf of the monarch at the opening of Parliament, with unprecedented freedom:

Every friend of this country must lament that a prince of so many great and amiable qualities, whom England truly reveres, can be brought to give the sanction of his sacred name to the most odious measures …. I wish as much as any man in the kingdom to see the honour of the crown maintained in a manner truly becoming royalty. I lament to see it sunk even to prostitution.

6

This could not be allowed to go unanswered. The ministry now issued a general warrant for the arrest of anyone connected with the publication. This raised the stakes. Until this point

The North Briton

had been the tool of what was, in essence, a dispute within the political elite. Now with the arrest of his publisher, printer, journeymen and hawkers (forty-nine in all), Wilkes had the opportunity he craved to test an issue of real importance: the limits of press freedom.

The legal actions revolved around two issues: whether Wilkes as a Member of Parliament enjoyed immunity from arrest for a libel (albeit a heinous one); and the validity of a general warrant, which named the crime rather than listing the alleged perpetrators by name. On both points

The North Briton

was triumphantly vindicated. Its printers were freed and awarded substantial damages for wrongful arrest. Wilkes became a celebrity. Before his trial Wilkes had fretted that his face was hardly known to the general public. Now the deficiency was repaired, first by a hostile but widely circulated print by William Hogarth (a Tory, and an enemy). Soon his features seemed to be everywhere: on broadside ballads celebrating his release, stamped on porcelain dishes, teapots and tobacco papers.

7

Such were the fruits of fame in eighteenth-century London. Despite muddying the waters with a conviction for obscenity and flight abroad, Wilkes continued to attract considerable

loyalty. His fight to be allowed to take his seat as an MP for Middlesex in 1768 and 1769 made his a national cause.

The emboldened press now pushed forward on other fronts.

The London Daily Post and General Advertiser

was largely an advertising paper until new editors, Henry Woodfall and his son Henry Sampson Woodfall, gave it a new lease of life. Rebranded as

The Public Advertiser

, their key innovation, to accompany the paper's enhanced coverage of domestic politics, was a series of trenchant political essays, published anonymously as the

Letters of Junius

. Strongly anti-ministerial in tone, in 1769 a letter addressed to the king resulted in the arrest of the younger Woodfall and several other editors whose papers had reprinted what was, in truth, an astonishingly direct and personal attack. ‘It is the misfortune of your life,’ Junius informed the king, ‘that you should never have been acquainted with the language of truth, until you have heard it in the complaints of your people.’

8

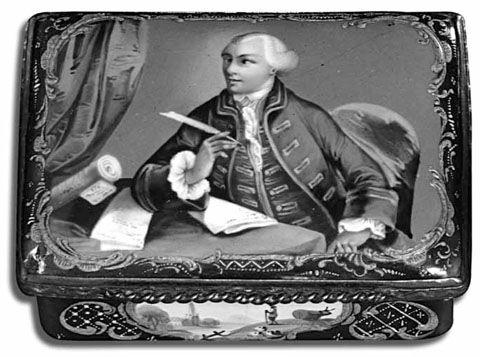

16.1 The fruits of celebrity. John Wilkes immortalised in enamel.

Three editors were committed to trial. Lord Chief Justice Mansfield directed the jury to convict, on the grounds that the judge alone could determine whether a seditious libel had occurred. The jury had solely to establish whether the accused were responsible for its publication. The jury's stubborn

refusal to follow this direction drastically rewrote the law of libel and much diminished its usefulness as a tool of press control. Though convictions for seditious libel still hung over the press, English regimes now had to be assured of a sympathetic jury, and not just a compliant judge; a much more demanding test.

Thus far the papers had directed their attacks at the conduct of government, a cause in which they could usually rely on the support of disaffected factions in the political elite. Now attention shifted to the prerogatives of Parliament itself. The right to publish Parliamentary proceedings had been a contested issue for over a century, ever since reporting had been encouraged by the Parliamentary opposition to Charles I in 1640. This freedom had been withdrawn by Charles II on the Restoration, and periodically reaffirmed and removed thereafter. This was generally an opposition cause, and one easily abandoned if the opposition found itself in power. The papers chipped away, publishing ‘extracts’ of speeches which frequently owed more to the imagination of the writer than any real knowledge of what had been said. Samuel Johnson, who built a considerable reputation as a Parliamentary reporter, confessed to friends that a much admired speech of the Elder Pitt was entirely Johnson's work: ‘that speech I wrote in a garret in Exeter Street’.

9