The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (53 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

The crucial moment came in 1778 when Panckoucke purchased control of the

Mercure de France

, the venerable but ailing successor to the

Mercure galant.

The

Mercure

had been established in 1672 as a monthly stablemate to the

Gazette

, but had failed to maintain its position in the proliferating eighteenth-century market for journals. Panckoucke transformed it into a weekly, and in the process built its circulation from 2,000 to 15,000. This coup had been

prepared by careful politics. By cultivating a relationship with the Comte de Vergennes, minister of foreign affairs from 1774, Panckoucke received the exclusive privilege to publish political news. That the foreign minister should have dealt such a critical blow to the official

Gazette

tells us much about the essential frivolity, as well as the brutality, of Ancien Régime politics. Other newspapers now had to pay Panckoucke for the privilege of reprinting his information. Secure in the confidence of both official Paris and the leading figures of the Enlightenment, Panckoucke flourished. By 1788 he had built up an extraordinary business empire, with 800 workmen and employees. His workshops and offices, it was said, were one of the sights of Paris.

13.4 Charles-Joseph Panckoucke, media mogul and Enlightenment man.

In 1789 Panckoucke won what would previously have been considered one of the greatest prizes of all: he became publisher of the

Gazette

. But these were strange times for the reporting of current affairs in France. Events would soon take a turn beyond the imagining of the philosophers of the old order. These events would test to destruction the capacities of the antiquated, prosperous print world of the Ancien Régime; men like Panckoucke, who had done well in its strangely constrained politics but extraordinarily diverse intellectual culture, would face a fight for survival.

The age of the journal witnessed the emergence of a thoughtful, self-confident industry that facilitated intellectual exchange over a wide spectrum of disciplines. For publishers this offered a welcome field of innovation in new ventures positioned between the established but sometimes complaisant world of book publishing and the turbulent world of pamphlets and ephemeral print. Even for the most established and conservative publishing houses, journals were an attractive economic proposition. They offered a regular and predictable sale thanks to the subscription system. For major new enterprises the compilation of a subscription list provided both valuable advertising and a means of testing the water before printing got underway. The extended friendship and correspondence network of the Republic of Letters provided a natural conduit for such information, and both editors and publishers were happy to move in these circles. The publication of even very substantial intellectual enterprises in numbered sections ensured that there was no risk of the unsold portion of an edition rotting in the warehouse, as had been the case with many overly ambitious scholarly works issued in the first centuries of print.

50

With periodicals, customers paid in advance and each issue had a built-in sequel, whereas books were individual events, dangerous and unpredictable in their success. It is no wonder that periodicals became the fastest -growing sector of eighteenth-century publishing.

CHAPTER 14

In Business

I

N

June 1637 Hans Baert found himself in a difficult spot. Baert was a wealthy Haarlem merchant, and in recent times he had involved himself heavily in the trade in tulips.

1

For a time he had prospered. The price of the bulbs had increased steadily, and more recently at a phenomenal rate. But in February of this year the bottom had dropped out of the market; and none of those who had bought from Baert at the higher prices would pay their debt.

The tulip trade was, it must be admitted, a very unusual form of commodity trading. These most exotic of plants flowered, often only for a week or two, in spring. The bulbs were then lifted, dried and in September replanted; thus for most of the trading year they could not be seen, or physically delivered to their new owners. This was little problem to the adventurous Dutch, who through their lengthy experience of long-distance voyages were used to managing a futures market, but it was bad news for Hans Baert. The price for tulips had reached its unlikely zenith in February 1637, when his bulbs were deep underground; now, in June, they had to be lifted, which could only be done in the presence of their new owners to prevent fraudulent substitution of less valuable varieties. Since his clients would not come, Baert stood to lose his money.

The tulipmania has gone down in history as one of the first great financial bubbles: an extravagant boom, followed by a ruinous bust. In fact, much of what was assumed to be known about this episode turns out to be myth. Most of those involved in the trade were prosperous citizens who could absorb the losses. There were few bankruptcies and the wider Dutch economy was barely affected. The tulipmania did not lead simple artisans, tempted into the market by hopes of a quick fortune, into penury. The most extravagant stories of destitute carpenters and weavers emanate from the moralising pamphlets that followed the collapse of the market.

2

During the sharp, and ultimately

spectacular rise in the prices of bulbs there was little adverse comment; in fact, the States of Holland were most concerned to profit from the boom by taxing the trade. What is in fact most extraordinary about this colourful episode is how little interest it evoked in the contemporary news media. That a pound of bulbs could change hands for 1,000 guilders (three years’ wages for a master carpenter) caused no adverse comment. Perhaps events moved too quickly. In five weeks Switzers, one of the most sought-after bulbs, went from 125 guilders a pound to a high of 1,500: 1,200 per cent appreciation in just over a month.

3

In this same year Amsterdam had two functioning newspapers, yet neither paid this sudden appreciation in the price of tulips much attention. Even in this sophisticated news market, the boom in tulip futures was a word-of-mouth phenomenon. Deals were struck and prices talked up in meetings between

bloemisten

, as those who got into the trade became known, in closed circles: at private dinners, in taverns, or in meetings in the gardens where the tulips were planted. The print media discovered the tulipmania only when the trade had collapsed, when pamphleteers had many things to say about greed, the credulity of traders, and the transitory nature of earthly wealth. Those who had had their fingers burned faced a deal of mockery. In 1637 the bad blood between thwarted sellers and rebellious buyers threatened to become a problem of public order. This too was unwelcome in a state where the good conduct of business and national reputation were closely aligned. In March the Burgomasters of Holland forbade ‘the little song and verses which are daily sold by the booksellers about the tulip trade’. The council sent round bailiffs to confiscate the printed copies.

4

It was time to draw a veil over the business, and move on.

The Business Press

The tulipmania casts an interesting light on the psychology of business in this period, but offers few hints regarding the development of a business press. This seems all the more surprising when we remember the important role that merchants had played in the creation of the international news market: from the business correspondence of the late Middle Ages, through the creation of the first courier services and the first commercial manuscript newsletters.

5

But at the point news became a commercial product it took a decisive turn away from the reporting of business news.

Avvisi

, and their successors the printed newspapers, offered almost exclusively political, diplomatic and military news. This could be of great importance to merchants with goods on the road, but it did not mesh with their day-to-day concerns with regard to the prices they would pay, or could charge, for commodities. Merchants also needed to

keep a close eye on the rates of exchange between Europe's various currencies. Although bills of exchange had functioned efficiently for the discharge of debt and the transfer of money over long distances for some centuries, fortunes could still be won and lost through trading in the currency markets.

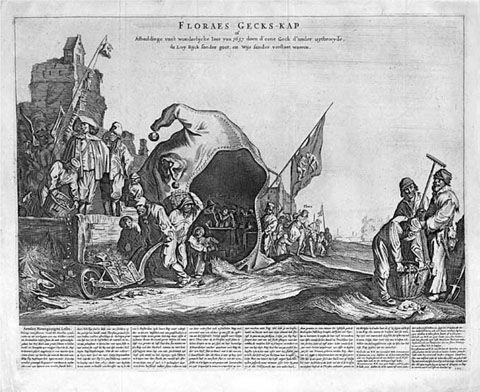

14.1 A satire on the tulipmania.

Bloemisten

conclude their bargains in a fool's cap while peasants cart off the worthless bulbs.

These more prosaic mercantile concerns spawned a different and highly specialised printed business literature: the publication of lists of commodity prices and exchange rates. Some of the most ephemeral of all forms of printed literature, they are far more likely to have been lost than to survive. The early history of the financial press can only be reconstructed from fragmentary evidence of flimsy scraps of print, often tucked away in bundles of commercial correspondence.

6

So although there is evidence that printed lists of commodity prices were published in Venice and Antwerp as early as the 1540s, the earliest surviving copies date from forty years later. These printed price lists were the very simplest form of print: a single strip of paper, characteristically about 14 by 48 centimetres. This suggests a large folio sheet had been set with two or three

settings of the same text across the page, which was then cut up. The format was closely modelled on the handwritten price lists compiled by brokers and agents in Europe's major trading centres in the medieval period. Examination of these early manuscript lists reveals a remarkable level of uniformity. Lists compiled in widely spread cities such as London and Damascus, and at very different dates, record much the same commodities (and often in the same order).

7

The commodities were named in Italian and this practice was largely continued into the print era, whether the price lists were issued in Venice, Frankfurt or Antwerp.

8

Amsterdam, where the commodities were listed in Dutch, was an exception; Hamburg also used Dutch in its earliest lists. All of these cities had published regular weekly lists by the end of the sixteenth century. London, Danzig and Lisbon soon followed. In the earliest surviving examples only the actual form was printed, leaving the date and the current prices to be added by hand.

In Amsterdam the fixing of prices was delegated to a committee of five brokers.

9

The data could then be passed to a scribal office for the prices to be added to a pre-printed form. By the middle of the seventeenth century Amsterdam had moved to a fully printed form, still produced under official supervision. The regulations established by the city burgomasters also stipulated the terms of sale: subscribers were to pay 4 guilders a year (one and a half stuivers per copy). So that merchants who traded in Amsterdam on an irregular basis could have access to them, individual issues could be purchased at the Exchange for 2 stuivers each. The commodities listed were grouped into convenient categories, and covered a wide range of raw materials and finished products, including spices, foodstuffs and a range of clothes and textiles. Of course those actually striking bargains would always want to check up on the latest prices, which could move quite significantly during the course of a week. This suggests that the printed sheets served primarily as a reference tool, particularly for traders who wanted to assemble a run of weekly lists and check how prices had moved over an extended period. That the Amsterdam lists were used in this way, and circulated widely both in the Netherlands and abroad, is indicated by the provision for subscribers to take two or more copies at a reduced rate: presumably to send the duplicates to out-of-town correspondents.