The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (40 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

The horror of Magdeburg shook even the weekly news-sheets out of their customary dispassionate detachment.

20

Newspapers on different sides of the confessional divide took contrasting perspectives. The Munich

Mercurii Ordinari Zeitung

offered a pious celebration of the Catholic victory. According to their report, probably derived from sources close to Tilly, the calamitous fire had been started by the Swedish troops defending the city, determined to deprive Tilly's troops of their plunder.

21

On the Protestant side the full horrors of the sack were captured by a highly rhetorical report from the Stettin

Reichs-Zeitungen

:

The heat was such that the inhabitants lost their courage, and there arose a screaming and lamentation so terrible that it defies description. To save their

children from the enemy mothers threw them into the flames and then hurled themselves into the fire.

22

Other heart-rending personal tragedies were told and retold in a cascade of publications, mostly, it must be said, published in Protestant cities. Catholic presses were relatively subdued; the scale of the civilian casualties seems to have diminished any triumphalism. Such a catastrophe proved also, perhaps happily, beyond the powers of the woodcut artists. Representations of the city's destruction were mostly conventional topographical battle scenes. Only a few cartoons make rather coy and inadequate reference to Tilly's rough wooing of a (fully clothed) maiden Magdeburg.

23

It was left once again to the pamphlet literature to tell the full gruesome story and draw the appropriate morals: for many Protestants, this was not only a tale of Catholic barbarity, but also a warning that only repentance and obedience to God's will would turn away His wrath.

24

The Lion of the North

The German Protestant cause was by 1630 in a desperate position: the prospect of a reversal of fortune seemed hopelessly remote. Thus when the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus offered himself as a new champion, the punch-drunk German princes initially held back. It is hard to blame them: the previous intervention by a Lutheran monarch, Christian IV of Denmark in 1625, had resulted in total fiasco, with the occupation of most of his lands by Catholic troops and the potential establishment of Albrecht von Wallenstein as the ruler of a new Habsburg satellite state in northern Germany. So when Gustavus Adolphus landed at Peenemünde in July 1630, even the carefully orchestrated symbolism of his arrival on the hundredth anniversary of the Confession of Augsburg could not persuade the German princes to risk another tilt against the might of Habsburg arms.

25

John George, Elector of Saxony, the pivotal leader of German Lutheranism, was especially reserved. It was only when Tilly turned from the destruction of Magdeburg to invade Saxon lands that John George was forced to embrace the Swedish alliance. The result was a crushing Swedish victory at Breitenfeld (17 September 1631). Within months the Swedish armies had occupied much of Germany.

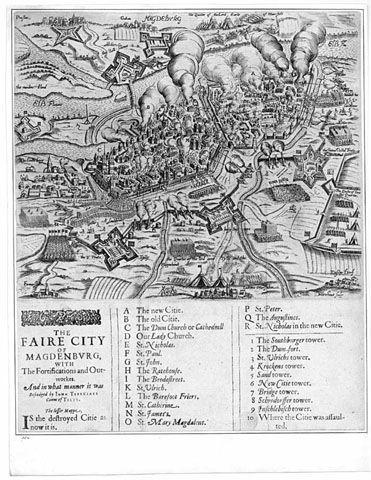

10.2 The tragedy of Magdeburg.

Swedish military success had a transformative effect on the German news world. The shock of Breitenfeld, the first significant Protestant battlefield victory of the entire conflict, led to a predictably ecstatic outpouring of celebratory literature on the Protestant side. Many woodcuts were published of the battle, and the most popular illustrative response made ironic reference to the purported reply of John George when Tilly demanded right of entry to Saxon lands prior to his invasion. ‘I perceive that the Saxon confectionery, which has been so long kept back, is at length to be set upon the table. But as is usual to mix it with nuts and garnish of all kinds, take care of your teeth.’ Now a

sequence of mocking cartoons pictured a bloated Tilly trying with evident discomfort to digest the German sweetmeats.

26

Other cartoons mocked Catholic confidence before Breitenfeld with a pair of woodcuts that show, first, a post messenger bringing news of a Catholic victory, before in the second the same messenger, now limping and wounded, reveals the true state of affairs.

27

The Swedish victory was transformative also in the sense that by their control of most of the German land mass the Swedes also controlled the news network. The Thurn and Taxis imperial postal service was now hopelessly disrupted. The arterial route between Brussels and Vienna could only be maintained by a long southward diversion to avoid enemy-controlled territory. Gustavus Adolphus filled the gap by establishing his own postal service, based on Frankfurt. To run it he recruited the erstwhile Frankfurt postmaster Johann von den Birghden, whose position had fallen victim to the increased confessional tensions of the late 1620s. In 1628 von den Birghden had been dismissed on the spurious grounds that his weekly newspaper had been filled with false reports prejudicial to the imperial cause.

28

His career in ruins, there was no reason for von den Birghden not to throw in his lot with Gustavus. Within a few months this remarkable man had restored the postal routes to Hamburg and Leipzig, and established two new itineraries. One led to Venice through safely Protestant Zurich; the other via Metz to Paris, to keep Gustavus in contact with his nervous and wily ally Cardinal Richelieu.

29

The period of Swedish dominance of German affairs was short-lived. In the spring of 1632 Gustavus resumed his apparently inexorable conquests, pressing deep into Bavaria and occupying Munich. Protestant allies were regaled with many exuberant cartoons featuring a rampant lion chasing a now chastened Bavarian bear.

30

A popular woodcut showed Gustavus surrounded by topographical views of the cities conquered by the Swedes: this went through many editions, as it had to be so frequently updated.

31

A popular scatological alternative showed a bloated Catholic priest, forced to regurgitate the fallen cities back into Protestant hands.

32

This year, 1632, represents the absolute high point of German political broadsheet production. A total of 350 recorded items are known, many of which survive in numerous copies. This is unusual for such ephemeral material, and is a sure indication that they were assiduously collected at the time they were first published.

33

The rising tensions between Gustavus and his Protestant allies remain unexpressed in the Protestant broadsheets, which instead continue to heap ridicule on the hapless Tilly. But when the armies next faced each other, at Lützen in November 1632, the Swedish victory was bought at a high price: Gustavus Adolphus, the Lion of the North, was fatally wounded. Initial reports in the newspapers reflect the complexity of this bloody and indecisive

engagement. Even when the outcome was known the Protestant papers were extremely reluctant to acknowledge that their champion had fallen. The confusion of the moment is captured by a Silesian paper which in eight pages carries three reports of the battle, printed in the order they came to hand. The first states quite correctly that Gustavus is dead; the second qualifies this with doubts; and the third, on the final page, declares that he is still alive and continuing the campaign against the remnants of Wallenstein's army.

34

Like a surreal modernist film where the narrative unfolds in reverse, these reports encapsulate the difficulties that still attended contemporary news gathering, particularly from the war zone.

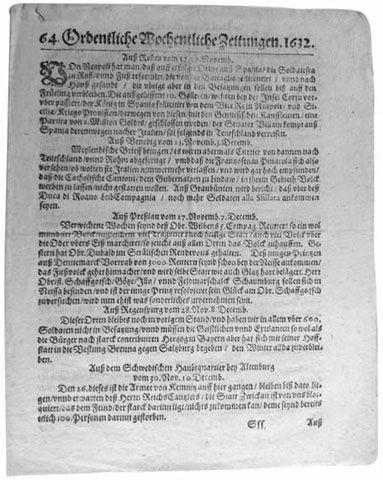

10.3 Von den Birghden in the service of the Swedes. Aside from the new postal routes, von den Birghden also resumed his newspaper. Note here the prominence of news from the Swedish headquarters.

The death of Gustavus Adolphus did not end Swedish involvement in the war. Management of the Swedish armies passed to Axel Oxenstierna, the administrative genius behind the logistical triumph of Swedish arms, and he successfully steadied the ship. But Swedish policy increasingly stressed dynastic and strategic priorities rather than the Messianic mission that had

fuelled the cult of Gustavus. Even after the catastrophic defeat of Nördlingen in 1634 the Swedes fought doggedly on to preserve a north German territory to bolster their aspirations to hegemony in the Baltic. The clarity of purpose that had characterised the conflict in the years 1630–2 now disappeared. In 1634 news publications recorded without regret the assassination of Wallenstein, an increasingly uncontrollable free agent put to death on the orders of his former imperial master. In 1635 France declared war on Spain, a conflict that would be pursued very largely in a campaign for Rhineland security. Catholic fought Catholic and increasingly Protestant fought Protestant: at the battle of Wittstock (4 October 1636), the great Swedish victory that arrested their decline in influence, their beaten opponents included the forces of Lutheran Saxony.

It was no surprise that an exhausted public yearned for peace. The ravaged German territories were precipitated into an extended economic decline. The printing industry and the news networks were both badly affected by the economic disruption. Production of political broadsheets declined rapidly, but enough remained to record the progressive disengagement of the German states from the wars on their territory. In 1635 the Lutheran states made peace with the Emperor. In 1643 the foreign powers were persuaded to join them in negotiations to end the war and resolve outstanding territorial claims.

The process of peace-making was agonisingly slow. Protestant and Catholic would not sit down together, so the Catholics met at Münster, and the Protestants at Osnabrück. Questions of precedence and procedure consumed most of the first year, a maddening overture perfectly satirised by a brilliant cartoon which shows the plenipotentiaries as dancers, manoeuvring for a better position.

35

To facilitate the negotiations and consultation with absent principals, several new postal networks were established. The imperial postal service, successfully restored after the Swedish defeat at Nördlingen, established direct lines between Münster and Linz, and between Münster and Brussels. This was the achievement of the redoubtable Alexandrine de Rye, widow of Leonhard von Taxis, who had taken over the management of the imperial post after her husband's unexpected death in 1628.

36

She ran the post for eighteen years, presiding over a restoration of the family fortunes which ensured that the Taxis would continue in possession of the postal privilege until their replacement by the Reichspost in the nineteenth century. Several of the other powers represented, including the Dutch United Provinces and Brandenburg, established their own direct courier service to Osnabrück. At last, in 1648, sufficient progress had been made to declare peace.

The Peace of Westphalia brought to an end thirty years of an immensely destructive conflict. The repeated incursions of even more disorderly armies had

taken a terrible toll on the fabric of German life. Some regions had lost over half their population, and would take generations to recover. So it seems strange to celebrate the extraordinary creative energies of the German news media in these years. Seventeenth-century Germany did not produce a Dürer or a Cranach, but its publishing entrepreneurs conjured from the tribulation what was, with the political broadsheet, a substantially new news medium.

For all that, the story told by these illustrated prints would be a very partial one. The execration of Tilly can be contrasted with an almost total neglect of Wallenstein. Whereas Gustavus Adolphus is celebrated in literally hundreds of prints, to go by the political broadsheets the Danish incursion of 1625 need hardly have taken place; the same could be said, very largely, of the French intervention after 1635.

How can one explain these disparities? The explanation must be that broadsheets play a particular role in news culture. They do not warn of a looming or present danger, as was certainly the case, for instance, with contemporary pamphlets. The pamphlet writers expressed their outrage at Frederick's acceptance of the Bohemian Crown; the cartoonists joined the fray only when he was ignominiously defeated. On the other side Tilly became the object of mockery only when he was humbled, not when his forces were victorious; the chorus of praise for Gustavus was unleashed only when he had won his first victory. Cartoonists, it seemed, prospered by sharing with their purchasers the moment of relief after the danger was past. Seventeenth-century satirists were by and large wise after the event: they restrict their praise or opprobrium to what has already happened and is already known.